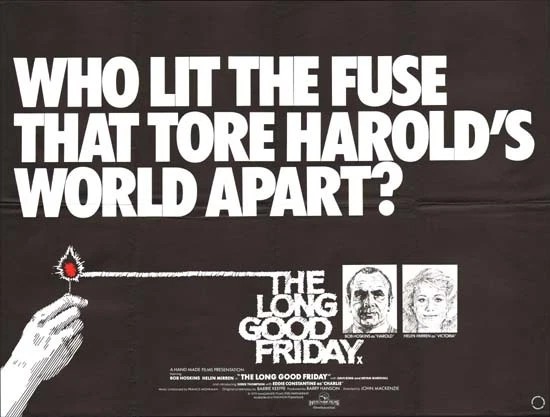

Surprisingly hardnosed for a British crime thriller. Surprisingly stylish and when the sting in the tail comes, it’s an emotional one, adding a deeper level to one of the main characters. In most crime picture – wherever they originate, Britain, Hollywood, France, Italy – the detectives may well complain to their colleagues about their superiors but they never take them on head-to-head and again and again. For that element alone, this is well worth watching.

The opening has you hooked, way head of its time, you would be more likely to see this type of approach in a picture from a top-name director, Alfred Hitchcock for example. A man, Marlowe (Robert Shaw) enters a derelict detached house carrying three parcels. He climbs a flight of stairs. With a key he opens a locked door. It might be a bedsit it’s so scarcely furnished except for the child’s bed. He sits down at the table, empties out two bottles of milk and some food. He opens a long parcel wrapped in paper and takes out a stuffed toy. He flips it over on its stomach, cuts open its back, pulls out the stuffing and from his last parcel removes a small bomb which he places in the empty space.

(At this point I have to explain that the toy is a gollywog, an innocent enough toy at the time but which has different connotations now, so is rarely mentioned, but this particular type of toy has a bearing on the plot, so forgive me if I make further mention of it.)

Next time we see him he’s wearing a chauffer’s uniform, picking up a small boy, Jonathan, (Piers Bishop) to take to school. Only, as you’ll have gathered, he has another destination in mind, but takes care not to frighten the child, to keep him distracted to the extent of the child thinking there’s nothing untoward as he is taken upstairs. He’s delighted with the toy, and not, at this point, too worried to be left alone.

Meanwhile, at the boy’s house, nanny Mrs Robinson (Helen Cherry) receives a telephone call from the school asking where the boy is. Just as the perplexed widowed father Anthony Chester (Alec Clunes) is given the news, Marlowe, now dressed in a suit, and carrying a Gladstone bag, appears at the door. Anthony greets him by name.

In the study Marlowe explains he has kidnapped the son, requires £50,000 in ransom, has planted a bomb set to go off the next morning at ten o’clock (hence the title), but will only release details of the child’s whereabouts once he is out of the country. Chester, a millionaire, has no qualms about paying up. Marlow is as cool as a cucumber. He has come up with the perfect crime. He will get off scot-free, become instantly rich and no one will come to any harm.

Except the nanny is listening at the door and dials 999. The local cops call in Scotland Yard. Assistant Commissioner Bewley (Alan Wheatley) assigns the case to Detective Inspector Parnell (John Gregson) quickly revealed as a tough nut, threatening to turn a suspect in a jewel robbery loose so that his pals will think he’s squealed and exact vengeance.

By the time, he reaches the house, Chester has gone off to withdraw the cash from the bank. Inside, Parnell confronts Marlowe. And so begins a game of cat-and-mouse. Marlowe holds firm, believing that the cop will give in to save the child, Parnell searches for a psychological weakness in the criminal’s makeup that he can use to crack him. Each convinced of their own mental strength in a battle with an innocent life at stake.

Chester returns with the money and is furious to discover the cop. When Parnell refuses to play along with handing over the cash to the kidnapper, Chester pulls out his ace, the old boys network, calling up Bewley, asking for Parnell to be removed from the case. Bewley, happy to do a favor for a wealthy pal, agrees. But Parnell refuses to go.

Bewley goes in person to confront his insubordinate officer. Still, Parnell refuses to budge, verbally attacking his smug superior, threatening to go to the newspapers.

While the pair are arguing, Chester loses his rag, physically attacking Marlowe. In the struggle, Marlowe falls back, hits his head and falls unconscious. Bewley, who has reluctantly agreed to let Parnell continue, now responds with spiteful glee. The cop will carry the can if the child dies.

Chester, meanwhile, is calling in the top medical experts to save Marlowe, money no object. But Parnell can’t afford to wait and enlarges the inquiry, putting out a public appeal, Marlowe’s face on the front page of the evening newspaper. But every other investigation can’t be halted just for this case, so Parnell is frustrated when various beat cops, originally going door-to-door, are pulled off onto other case.

Meanwhile, we already know Jonathan has worked out something is wrong, But the window is sealed with steel mesh and the door is locked and eventually he goes to sleep cuddling the deadly toy.

Marlowe shows no sign of recovery and dies. Bewley ups the stakes against Parnell. A beat cop looks at the outside of the house in question but walks away. Parnell gets a tip-off that leads him to a nightclub called the Gollywog Club and encounters Marlowe’s parents who run the place. Their name is Maddow. They haven’t seen their son in several months and while they accept he’s a criminal, the mother reminisces about what a loving boy he was.

Eventually, Parnell finds the estate agent who rented the property to Marlowe. By now they have just five minutes to get to the property.

They arrive a few minutes after the deadline.

But Jonathan has inadvertently saved his own skin, and ironically the plan has backfired because of Marlowe’s insistence on hiding the bomb in a stuffed toy of sentimental value rather than secreting it in a cupboard or somewhere the child would not have looked, and even if he found it wouldn’t know what it was.

After waking up Jonathan has washed his face and hands and decides the toy could do with a bit of tidying up the same so dunks it in a sink full of water, thus nullifying the bomb.

Parnell goes home, welcomed by wife and – child the same age as Jonathan.

So, yes, much of the tale is par for the course, several twists to up the tension, but Parnell’s duels with his boss put this on a different level, and the realisation at the end that he has managed to set aside the feelings for his own child. And it’s also elevated by the direction of veteran Lance Comfort (Devils of Darkness, 1965) who takes time out – in an era when such features were usually cut to the bone – to add atmosphere. The first and last scenes are outstanding for different reasons and the two verbal duels make for a fascinating movie.

Stronger cast than most in this budget category – John Gregson (Faces in the Dark, 1960) and Robert Shaw (Jaws, 1975) bring cool steel to the affair.

Though little-know, Tomorrow at Ten has been acclaimed as one of the top 15 British crime pictures made between 1945 and 1970 and I wholeheartedly agree.

Another welcome revival from Talking Pictures TV.