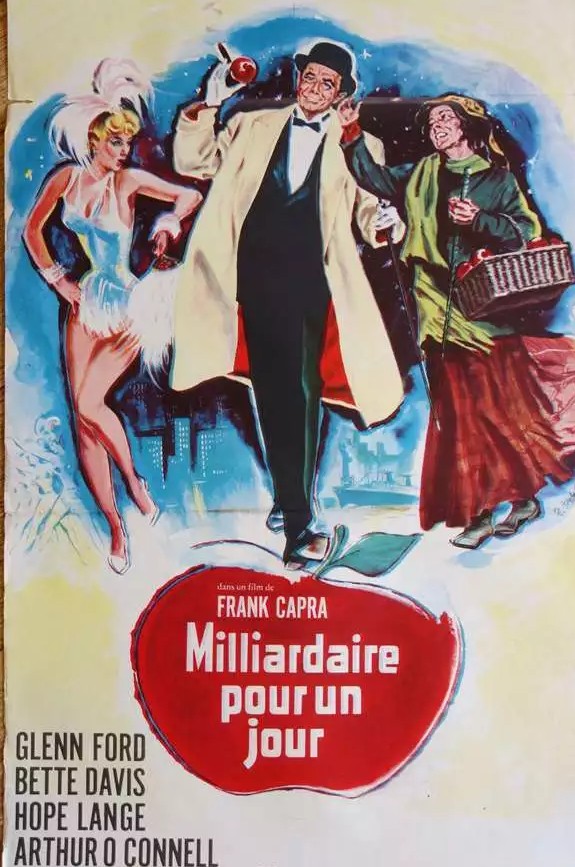

Frank Capra was yesterday’s man – one movie in a decade – and 15 years away from the consolation of knowing that his flop It’s A Wonderful Life (1948) was on its way to becoming, arguably, along with The Wizard of Oz (1939), America’s most beloved picture thanks to annual Xmas showings on television and subsequently in the cinema.

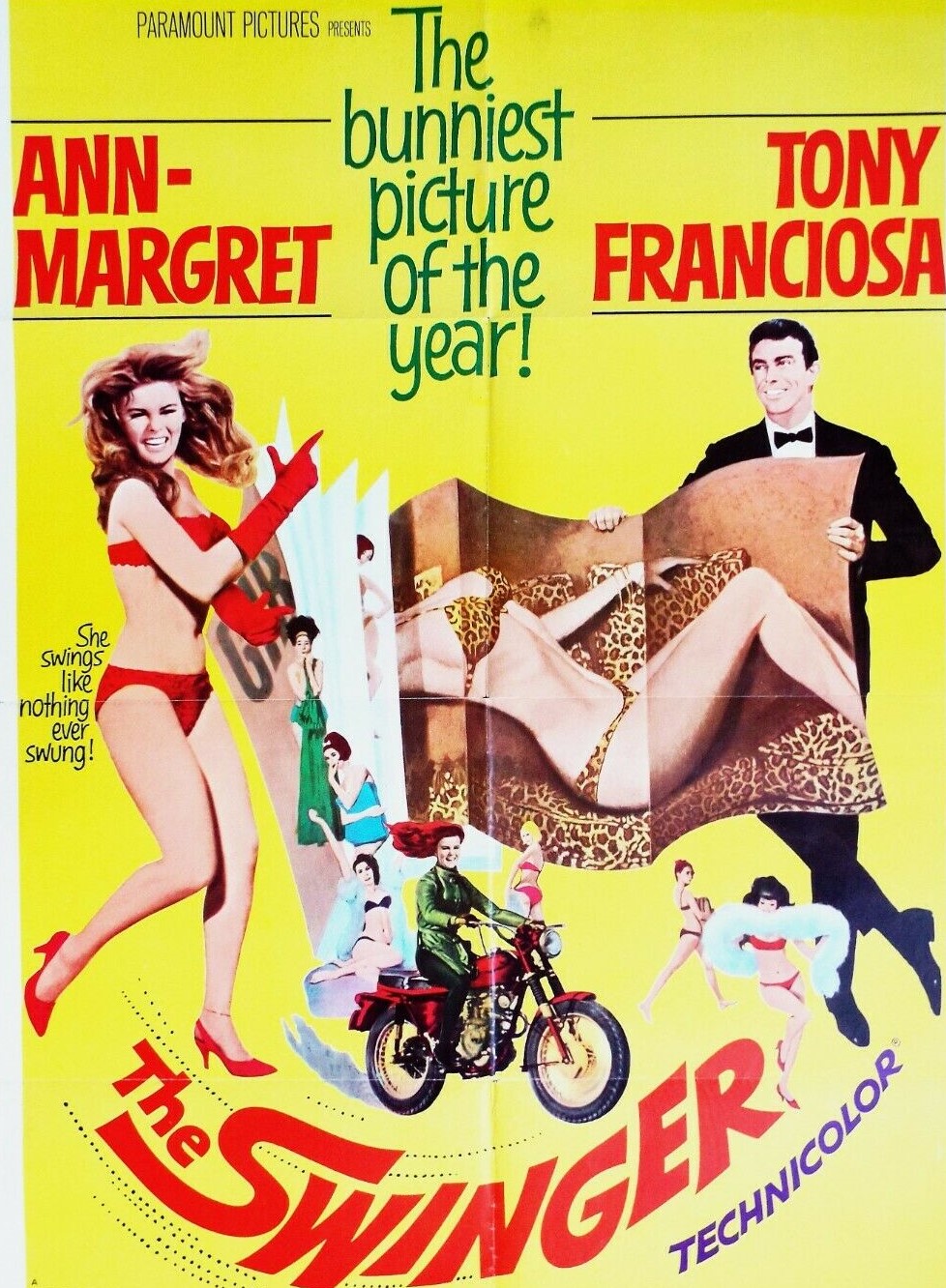

There’s nothing new here, either, it’s a remake of his Lady for a Day (1933) and it’s more of a fable lacking punch than some of his more famous pictures. And the main interest for contemporary audiences may well be that it marks the debut of Ann-Margret (The Swinger, 1966) who gets to sing but not shake her booty in trademark fashion. And it takes forever to wind up to a pitch. We’ve got to wade through three subplots before it gets going.

First of all Prohibition gangster Dave (Glenn Ford) meets up with the daughter Queenie (Hope Lang) of a deceased club owner who’s in hock for $20,000. Dave is much taken by the earnest Queen’s determination to repay the debt at the rate of five bucks a week. For no reason at all except narrative necessity, she’s turned into a nightclub singing sensation.

When Prohibition ends, big-time Chicago gangster Steve Darcey (Sheldon Leonard) plans to muscle in on the New York rackets and it takes all Dave’s suave bluster to keep him, temporarily, at bay. The end of Prohibition comes as a relief to Queenie and with the nightclub shut down she agrees to marry Dave with the proviso that he give up the gangster life and retire to her home town in Maryland and they become an ordinary couple.

Very much on the fringes of this is Apple Annie (Bette Davis), a street panhandler who sells “lucky” apples, one her most satisfied customers being Dave. When her illegitimate daughter Louise (Ann-Margret) returns from Spain to New York with rich beau Carlos (Peter Mann) in tow, Annie’s in a pickle, because she’s been keeping up the pretence of being a wealthy woman.

Queenie insists they help Annie to maintain her charade and Dave goes along with the idea because he’s worried his luck will run out. So Annie is turned into a sophisticate, manners polished, furnished with a luxurious apartment, including a butler, and fake husband Henry (Thomas Mitchell).

None of the stars seem to know how to handle the material, and for most of the time they act as if in a pastiche, like they were throwing winks to the audience. Glenn Ford (Fate Is the Hunter, 1964), generally adept at comedy, plays this all wrong. He wanted the part so badly he helped finance the picture. Bette Davis (Whatever Happened to Baby Jane, 1962) overacts, as does Peter Falk (Murder Inc, 1961), though the Academy didn’t think so and threw him a second Oscar nomination. Hope Lang and Ann-Margret, playing it straight, get it right, though the latter, vivacious personality to the fore, wins that battle by more than a nose. Might well have worked if original choice Frank Sinatra hadn’t ankled the project.

Hal Kanter and Harry Tugend wrote the remake, based on a Damon Runyon story. It was always a tricky business to capture the stylistic essence of Runyon, Guys and Dolls (1955) the most effective transition, Lady for a Day better than this and Little Miss Marker filmed three times.

Once the Bette Davis pretence enters the equation, the tale takes on some narrative drive and the quintessential Capra shines through. But it’s too little too late.

Not the swansong Capra anticipated, but he only has himself to blame.