Producer Harold Mirisch purchased the rights to the 1960 Broadway hit play by Lilliam Hellman as a way of hooking William Wyler. He had originally signed up the director in the mid-1950s when his Paramount contract came to an end. This was before the Mirisch Brothers was an independent production entity and later responsible for films like The Apartment (1960), The Magnificent Seven (1960), West Side Story (1961) and The Great Escape (1963). At that point Mirisch worked for Allied, the upmarket offshoot of B-picture outfit Monogram. Allied backed Wyler’s Oscar-nominated western Friendly Persuasion (1956).

In 1960 Wyler was the most celebrated Hollywood director of the era, not just with three Oscars and ten nominations, but riding as high as anyone ever had after the monumental critical and commercial success of Ben-Hur (1959). He had his pick of the projects and had shown “great eagerness” to do Toys in the Attic. He was friends with the playwright Lillian Hellman and had filmed These Three (1936) from her stage play The Children’s Hour and The Little Foxes (1941) from her original screenplay.

But Wyler decided instead to opt for a remake of The Children’s Hour (1961), assuming that changes in public perceptions would permit him to bring to the fore the lesbian elements kept hidden in his previous adaptation, but, critically, it was a Mirisch production.

In his absence, the Mirisch Bros decided to stick with Toys in the Attic, possibly to bolster their attempt to be seen as a purveyor of serious pictures and hence a contender for Oscars, which would solidify their reputation, as would soon be the case. After consultations with distribution and funding partner, United Artists, “it was decided that…since we had considerable investment in (Toys in the Attic)… we should try and put together a film,” explained Walter Mirisch.

Next in line for directorial consideration was Richard Brooks who had acquired a reputation for adapting literary properties after The Brothers Karamazov (1958), Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958) and Elmer Gantry (1960). Initially, Brooks “had been so insistent and enthusiastic” about becoming involved. However, he, too, rejected the opportunity. He, too, after Oscar and commercial success, was riding high. “It was not because he did not wish to work with the Mirisches because he would be delighted to make a picture for them…but he felt it would be wrong for his career to do a film so similar in mood and background as the one he was working on, Sweet Bird of Youth (1962).”

In fact, it was probably more to do with his financial demands. He wanted $400,000 a picture, which was extremely high at the time, plus “a drawing account of $2,000 a week” (i.e. payment in advance of an actual production). While Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and Elmer Gantry had been box office hits, they were nothing like Ben-Hur. And Brooks already had other pictures in mind. He had purchased a book called Goodbye My Son – never filmed – and was already revving up for Lord Jim (1965) funded by Columbia.

Walter Mirisch eventually settled on television director George Roy Hill (Thoroughly Modern Millie, 1967). This would have been his debut except preparations for the movie dragged on and in between Hill helmed Period of Adjustment (1962), an adaptation of another play, this time by Tennessee Williams. He would later direct Hawaii (1966) for Mirisch.

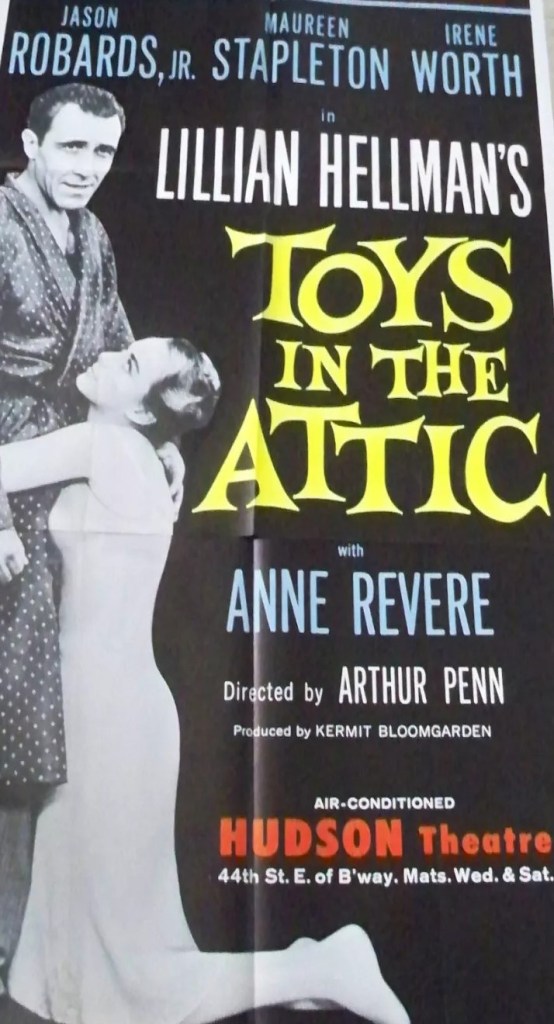

The play had been a significant hit, running for just over a year on Broadway at the Hudson Theater, and making $129,000 profit on a $125,000 investment, though it incurred a loss of $48,000 on a subsequent tour. Hellman did pretty well out of it too. She received ten per cent of the gross and twenty per cent of the profit – a total of around $36,000 – exceptionally good going for a playwright, especially when other monies would be forthcoming from movie rights and foreign and amateur runs. Director Arthur Penn’s share of gross and profit came to over $10,000 in addition to a $5,000 fee.

Turning a play or musical into a movie came with one inbuilt problem. It was inevitably subject to delay. No movie could go into production until the play had exhausted its theatrical (as in stage-play) possibilities. In this case, that meant 58 weeks in the original run and then another 20 weeks once it hit the road. Any contract with a significant movie player would have to include the possibility that in the meantime star or director would have lined up other projects while awaiting the green light on this one, and that in itself could cause further hold-ups.

Hill was in greater demand than Mirisch anticipated, juggling four separate projects – Period of Adjustment, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich for MGM (never made), and the $2.5 million A Bullet for Charlemagne starring Sidney Poitier (not made) as well as Toys in the Attic.

Jason Robards, star of the play, was the obvious contender for the movie role. But he lacked box office cachet, so he was bypassed in favor of Dean Martin, “an attractive motion-picture figure.” However, in the time it took the movie version of the play to reach the public, Robards was potentially a screen star. He had bought himself out his stage contract after 37 weeks – paying $3,950 for the privilege – having been offered second billing on By Love Possessed (1961) opposite Lana Turner, and in Twentieth Century Fox’s ambitious mounting of Tender Is the Night (1962) opposite Jennifer Jones. While Robards would never become as big a star as Dean Martin, he was the superior actor, later adding two Oscars and one nomination to his name.

In addition to being much better known to cinema audiences than Robards, “we felt he (Martin) would bring humor to it” – Martin having originally made a splash as part of the Martin-Lewis comedy team of the 1950s – “as well as an audience that might expand the normal constituency of that type of film.” Trade magazine Box Office agreed with the decision, viewing Martin as a “good choice for the haunted show-off.”

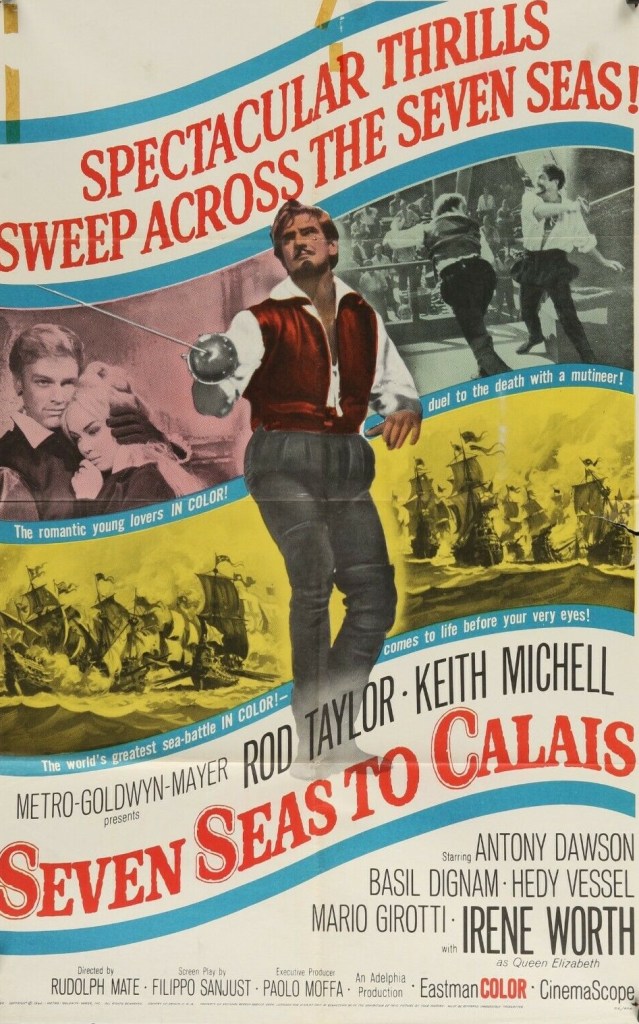

The play’s other stars – Oscar nominee (and later winner) Maureen Stapleton (The Fugitive Kind, 1960) – and Irene Worth (Seven Seas to Calais, 1962) – were ignored in favor of Geraldine Page, who incidentally scored an Oscar nomination in Summer and Smoke, and Wendy Hiller (Sons and Lovers, 1960), who already had an Oscar. Shooting began on September 16, 1962. Hill tried to “inject more suspense, more action, more melodrama into the movie version,” without cheapening the material. He was convinced the hiring of Martin was inspired, and would prove a personal turning point, as he gives “the best dramatic job of his career.”

Titles didn’t matter so much on Broadway, plays sold on the name of the writer or the star. Mirisch feared Toys in the Attic would either mean nothing to a general audience ignorant of the picture’s origins or be considered so obscure as to serve to confuse them. So, they planned to rename it Fever Street or “some sensational substitute.” Hill was furious, pointing out the “violence of his feelings” to this title. He complained that “others will assume that it is an exploitation title…a cheap gimmick to get people into the theater (cinema) … automatically puts the picture in a low budget quickie picture category that might be appropriate for 42nd St all-night houses or a second feature at Loews 86 St.”

Hill felt changing the title would demonstrate that Mirisch was “ashamed to have bought the play Toys in the Attic, have no faith in the picture, are resorting to panic tactics to get some money out.” And that Fever Street would have the opposite effect, and “keep people away in droves.” His impassioned plea worked, and the original title remained.

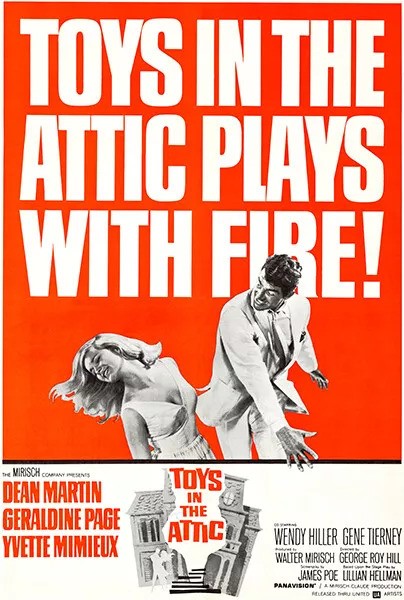

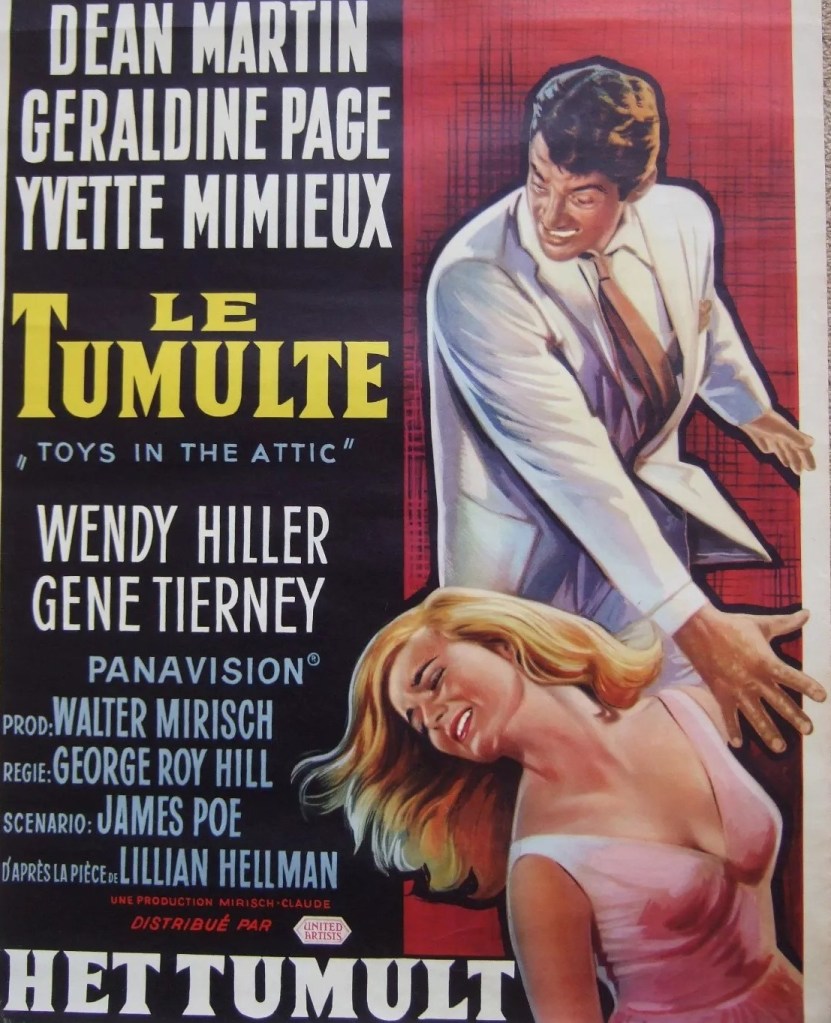

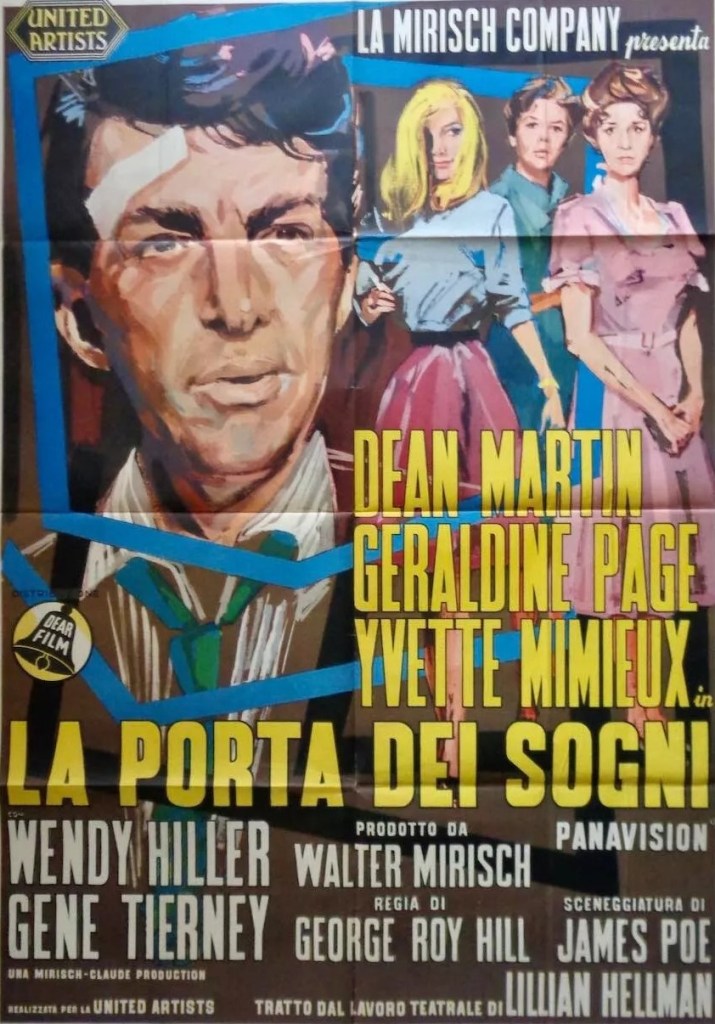

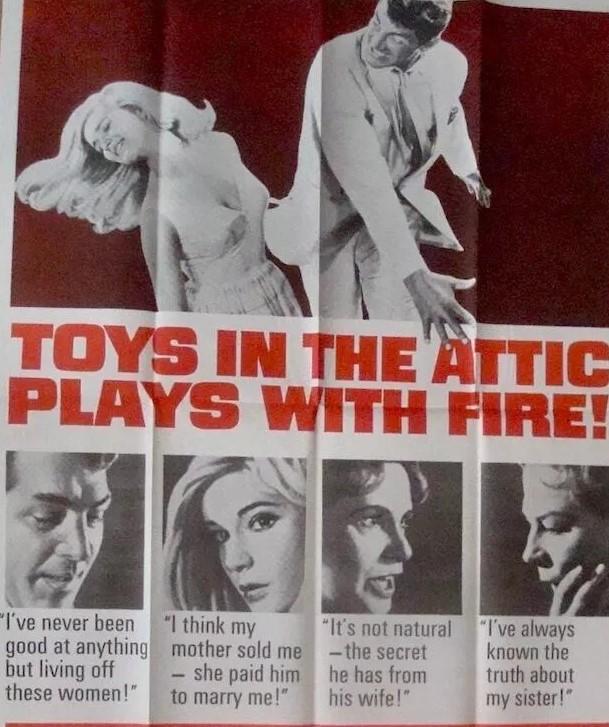

While backing down on the title, Mirisch veered towards the exploitative in the main poster which showed Dean Martin slugging Yvette Mimieux.

However, United Artists remained in two minds about the release policy. Despite the prestige of being chosen for the San Sebastian Festival, United Artists opted to open it in New York as part of a “showcase” run. That was a relativelynew distribution notion, a version of regional wide release. It would eventually be refined to allow several weeks in prestigious first run venues first, but inclusion in this release pattern meant first run was simultaneous with an opening in – in this case – another 20 New York neighbourhood cinemas. Had UA had more faith in the project, it might have benefitted from an opening just in first run. The $55,000 first week from two first run houses on Broadway was judged a “wow” result by Variety. First run in other major cities suggested a prestige title – “very stout” $15,000 in Boston, a “sock” $14,000 in Washington D.C., “neat” $14,000 in Buffalo, while it was “bright” in Kansas City ($8,000), Los Angeles ($10,000) and Chicago ($18,000).

Hill’s concerns about United Artists’ ability to sell the picture were mirrored in the result. “It did not turn out well,” concluded Walter Mirich, “It’s a grim story. It was not well reviewed and was not financially successful.” Part of the reason for its failure, he argued, was that it “probably appeared at the end of a cycle” of American Broadway adaptations of heavy Tennessee Williams dramas.

While the movie came in $70,000 below the $2.1 million budget, the savings were put down to the fact that it was filmed in black-and-white rather than color, as had been originally envisioned. The box office followed a common, but disturbing, trajectory, a big hit in the big cities, mostly ignored elsewhere. But it was not as bad as all that. Mirisch tallied the domestic box office as $1.7 million with another $900,000 from the overseas box office. By its estimation, once marketing costs were considered, it was facing a loss of $183,000. But that was before television revenue entered the equation and that should have at the very least, made up the difference. There were various pickings later on, too, picked up by CPI under the “Best of Broadway” label in 1981.

SOURCES: Walter Mirisch, I Thought we Were Making Movies, Not History (University of Wisconsin press, 2008) p157-159. Leon Goldberg, “Office Rushgram: Final Cost on Toys in the Attic, May 13, 1964, United Artists Files, Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research; “Mirisch Pictures Box Office Figures,” UA Files; Letter,” George Roy Hill to Walter Mirisch, March 15, 1963, UA Files; “Lillian Hellman Could Mop Up if Toys Clicks,” Variety, February 4, 1960, p103; “Toys Exit,” Variety, January 18, 1961, p72; “George Roy Hill To Direct Toys for Mirisch Co,” Box Office, January 22, 1962, pE8; “Hollywood Report,” Box Office, February 22, 1962, p16; “George Roy Hill Announces First Film on UA Deal,” Box Office, March 19, 1962, p16; “Bloomgarden Had Varied Fortune,” Variety, August 29, 1962, p49; “Toys in Attic Chosen for San Sebastian Festival,” Box Office, June 10, 1963, pE8; “Premiere Showcase,” Variety, July 31, 1963, p22. Box office figures from Variety issues dated August 7, August 14, August 21, September 4, September 11 and October 23.