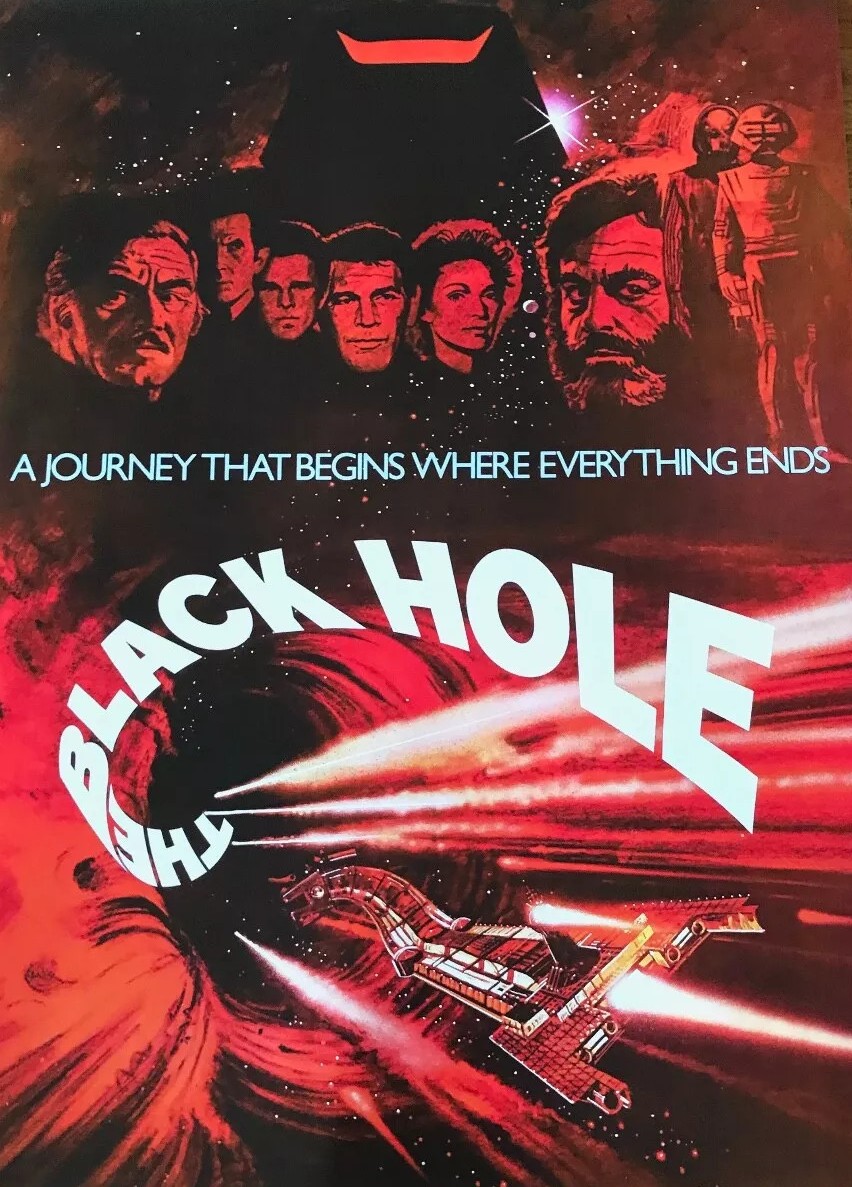

Think of this as having been made before Star Wars (1977), Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Alien (1979), heck even Star Trek (1979), changed the sci fi world forever and imagine it’s a huge advance SFX-wise on the 1950s vanguard of sci fi pictures and you’ll probably come away very happy. A lot to admire in the matte work and some groundbreaking effects and actually the story – mad scientist lost in space – has a bit more grit than was normal for the genre.

But it’s laden down with talk and the action when it comes resembles nothing more than a first draft stab at the light sabers of Star Wars and clunky robotic figures that come across like prehistoric Stormtroopers. A bit more light-hearted comedy than in the other three mentioned, various quips at the expense of the robots.

Scientists aboard space ship USS Palomino, a research vessel looking for life in space, is astonished to discover, hovering on the edge of a black hole, a missing spaceship USS Cygnus and are even more astonished to find out it’s not uninhabited, still on board is heavily-bearded Dr Hans Reinhardt (Maximilian Schell) and an army of robots that he has miraculously fashioned during his time lost in space.

This is a bit of an emotional blow to Dr Kate McCrae (Yvette Mimieux) whose father had been part of the crew of the Cygnus. Dr Reinhardt seems kosher enough except for his idea of, in the true spirit of space adventure, blasting off through the black hole. Although Reinhardt has been exceptionally clever in monitoring the invasion from the visitors and nullifying any threat with a blast from invisible laser, once they are on board that monitoring capability appears to vanish, allowing the visitors to search the ship where they find out that Reinhardt’s story doesn’t seem to add up.

Apart from Dr McCrae, the other personnel from the Palomino comprises Capt Dan Holland (Robert Forster), Dr Durant (Anthony Perkins) – the most inclined to follow Reinhardt into the greatest danger in the universe – quip merchant Lt Pizer (Joseph Bottoms) and dogsbody Harry (Ernest Borgnine). Plus there’s a cute robot Vincent (Roddy McDowall) constructed along even more rudimentary lines than R2-D2.

Vincent turns out to be a whiz at a basic version of a computer game, something between Space Invaders and Kong. But his main task is to wind up the crew with a head teacher’s supply of wisdom, spouted at the most inopportune moment. Except for the chest-bursting appearance of Alien, this might have garnered more kudos for the creepy mystery element – Reinhardt has lobotomized his crew members, turning them into these jerky robots, after they mutinied in revolt against his plan to dive into the black hole. Dr McCrae nearly joins the lobotomy brigade. And once she’s rescued it’s a firefight all the way. A stray meteor is on hand to add further jeopardy. And in the end the good guys are forced to plunge into the apparent abyss of the black hole, only to be guided by some angelic light and come out the other end unscathed, no worse for enduring the kind of phantasmagoric light show Stanley Kubrick put on in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

By this point Maximilian Schell (Judgement at Nuremberg, 1961) was an accomplished bad guy, covering up inherent malignancy with charm and scientific gobbledegook. Joseph Bottoms (The Dove, 1974) is the pick of the incoming crew but that’s because he’s been dealt a stack of flippant lines. Anthony Perkins at least gets to waver from the straight-laced. But everyone else is a cipher, even Yvette Mimieux (Light in the Piazza, 1962) who might have been due more heavy-duty emotion.

This was the 1970s version of the all-star cast, all the actors at one point enjoying a spot in the Hollywood sun, but now all supporting players. Schell was variably billed in pictures like St Ives (1976), Cross of Iron (1977) and Julia (1977). Robert Forster (Medium Cool, 1969) hadn’t been in a movie in six years. Anthony Perkins was waiting for a Psycho reboot to reboot his career – only another four years to go. Yvette Mimieux had only made four previous movies during the 1970s including Jackson County Jail (1976). The most dependable of these dependables was Ernest Borgnine (The Adventurers, 1970), for whom this was the 24th movie of the decade, including such fare as Willard (1971), The Poseidon Adventure (1972) and Hustle (1975).

It didn’t prove a breakout picture for director Gary Nelson (Freaky Friday, 1976), Screenplay credits went to Jeb Rosebrook (Junior Bonner, 1972) and female television veteran Gerry Day.

Sci fi the Disney way.