Funny how you remember the circumstances of seeing a film for the first time. This was important for me because it was the start of me digging into the vast heritage of the movies rather than watching just what was showing at my local cinema. I can’t pin down the exact date, but I have a feeling I was still at school, though in the advanced stage of that academia. I saw this on a 16mm print in a terraced house sitting on the hard kind of seats you used to get in assembly halls.

The location was the Scottish Film Council, the predecessor of the Glasgow Film Theatre, which was located in the city’s West End. The occasion was the final film in an eight-movie retrospective of Elia Kazan pictures. Either before or after I attended a similar Fellini retrospective. Certain more controversial films were omitted, so no Gentleman’s Agreement (1947), Pinky (1948) or Baby Doll (1956) and although this was the early 1970s no room for Splendor in the Grass (1961), America, America (1963) or The Arrangement (1969). Afterwards, there was a cup of tea and a biscuit and a discussion hosted by John Brown, who in my memory smoked small cigars, later a television and screen writer.

It was an introduction for me to the power of the retrospective, to view a huge number of a director’s films back-to-back (the screenings were weekly) and to understand the thematic symmetry of their work. Kazan predated the New Hollywood of the late 1960s and 1970s, so, although his movies usually challenged existing norms, these days they are often viewed as more stolid than of the first rank, his cause not helped by revelations that he named names at the anti-Communist hearings of the 1950s.

Wild River is one of those films that plays completely differently now thanks to the intervening decades. A contemporary audience is unlikely to sympathize with hero Chuck Glover (Montgomery Clift) whose job is to persuade farmers in the early 1930s to clear out of the way of land that is going to be swamped with water to supply a new dam that would serve to both control the catastrophic flooding in the Tennessee Valley and bring electricity to an impoverished area.

These days ageing landowner Ella Garth (Jo Van Fleet) would attract massive publicity in her fight to avoid being shifted from land that had been in her family for generations, especially as she claims that dams go “against nature.”. And no matter how sympathetic a character like Chuck might be to her circumstances he would be viewed as a more well-meaning-than-most government apparatchik.

And in some respects, this plays much better as one of the few movies exploring the plight of the African American at the hands of the racist authorities. Chuck incites local hostility when he recruits Blacks to work alongside Whites, in the end conceding that they should work in separate crews. But he comes unstuck when he sticks to the principle that they should be paid the same, more than double the going daily rate for Blacks.

In consequence he is beaten up and, worse, a gang of thugs attack the house inhabited by his lover Carol (Lee Remick) and her two young children and the cops, when they arrive, are apt to condone the violence.

Ella takes a maternal attitude to her Black workforce and while certainly nobody received abusive treatment at her hands she has a patronizing manner, though in the end she encourages them to leave.

Despite his democratic and anti-racist views, Chuck comes over as a clever dick, thinking his smooth eastern charm can convince the reluctant woman to move and for the racists to abandon their inherent racism.

I’m not sure about the widowed Carol either, she almost seems to be throwing herself at the first decent man who comes her way. While she is already being courted by a local fellow, who is more decent than the rest, that is clearly going to be a marriage of convenience, but what exactly makes Chuck so much more an attractive proposition is never made entirely clear except that, for narrative purposes, it creates a romantic deadline – is she just a fling, thrown over when he heads home – and a whiff of tension.

However, marriage to the other man would have made her just a passive housewife, whereas she realizes that in many ways she is smarter than Chuck, more grounded, and she would have more freedom in this kind of match.

Oddly enough, there’s a Hitchcock vibe here. At several points the camera tracks Glover in longshot as he appears to be heading for trouble.

The racist elements give this its bite rather than any ecological issues. The acting is certainly of high quality, Montgomery Clift (The Misfits, 1961), less mannered than in some of his work, in one of his last great roles. It’s an interesting part. At one point he wishes he could once in a while win a physical fight, and it’s Carol who is more likely to show the venom required in battle.

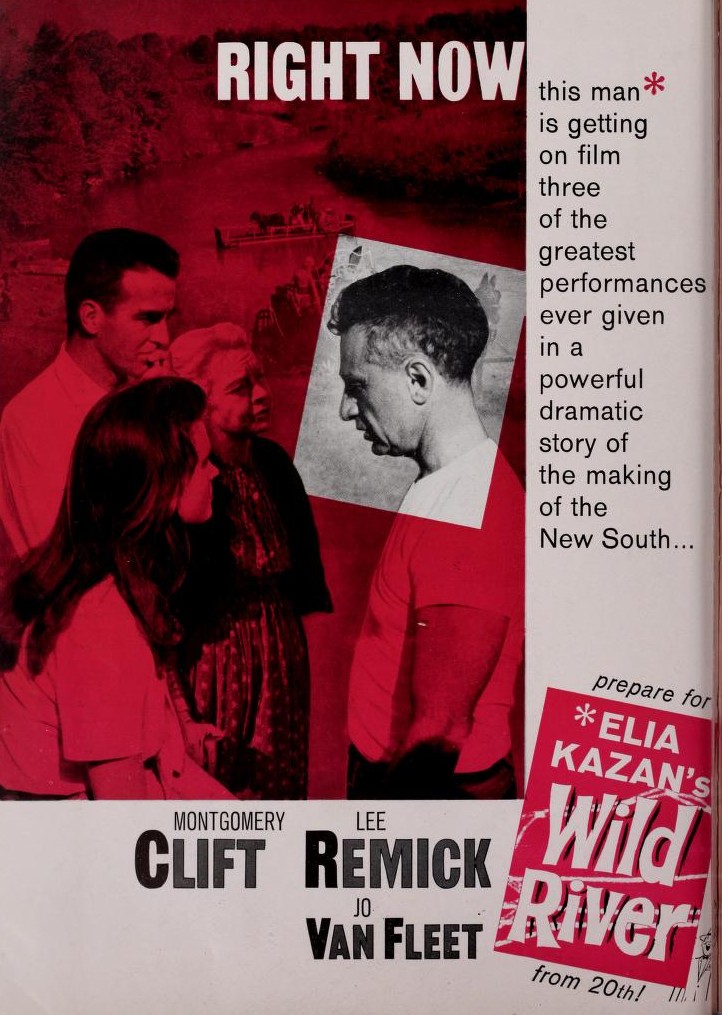

Lee Remick (No Way To Treat A Lady, 1968) continued to build on her exceptional promise. Jo Van Fleet (Cool Hand Luke, 1967) gets her teeth into the kind of role most actors dream of. You can spot Bruce Dern (Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, 2019) in his first role.

An unusual approach to the screenplay, too, by Paul Osborn (The World of Suzie Wong, 1960). Like The Towering Inferno (1974) a decade later, this derived from two novels – Dunbar’s Cove by Borden Deal and Mud on the Stars by William Bradford Huie (The Americanization of Emily, 1964).

Despite my ecological reservations, still stands up..

Something for you:

“The working titles for this film were Mud on the Stars, Time and Tide, The Swift Season and As the River Rises. When initial grosses for the film fell below Twentieth Century-Fox’s expectations, the title was temporarily changed to The Woman and the Wild River to accompany an advertising campaign emphasizing the love affair between the characters portrayed by Montgomery Clift and Lee Remick. Both of the novels on which the film was based, William Bradford Huie’s Mud on the Stars and Borden Deal’s Dunbar’s Cove, examined the impact of progress on the rural South in the decades preceding World War II. Wild River was the first film based on a work by Huie, whose novels had earlier been deemed too controversial for the screen. In a NYT interview dated Feb 1960, Huie noted that six films based on his work were currently in production, including Wild River, a situation made possible by “the recent liberalization of the industry’s self-censorship code.” The 1962 film The Outsider (see above) and the 1964 film The Americanization of Emily (see above) were also based on Huie’s works.

The film’s prologue consists of black-and-white footage of a raging flood and the devastation left in its wake, followed by a newsreel-style interview with a survivor. An offscreen narrator provides the film’s historical background, stating that on 18 May 1933, Congress created the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), a massive public works program designed to end the loss of life and property caused by the overflowing of the Tennessee River. According to a modern source, the black-and-white opening footage is taken from Pare Lorentz’s 1930 documentary, The River. Although reviews for Wild River list Robert Earl Jones’s character as “Ben,” his character’s name in the film is “Sam Johnson.” Wild River marked Bruce Dern’s motion picture debut.

DV news items dated Aug 1957 and Sep and Oct 1958 reported that first Ben Maddow and then Calder Willingham had been signed to adapt Mud on the Stars for Elia Kazan. However, these writers are not credited onscreen and the extent of their participation in the finished film has not been determined. A modern source reports that Kazan had hoped to write the script himself, but after a number of unsuccessful drafts, worked closely with Maddow and Willingham before hiring Paul Osborn. Nine drafts of the script were written and additional working titles reportedly included God’s Valley, The Coming of Spring and New Face in the Valley. According to DV and HR news items dated Mar 1959, Marilyn Monroe was scheduled to play the female lead. In his memoirs, Kazan recounted that Twentieth Century-Fox executives urged him to hire Monroe, an idea he called “absurd.” Kazan added that he never considered anyone for the role but Lee Remick, whom he had directed in his 1956 film A Face in the Crowd (see above).

Wild River was shot entirely on location in Tennessee, in the towns of Cleveland, where the cast and crew were lodged, and Charleston, and on Lake Chickamauga and the Hiwassee River. The large set used for the Garth farmhouse took two months to construct at a cost of $40,000 and was subsequently burnt down for one of the film’s final scenes. Eighty percent of the film’s approximately fifty speaking parts were filled by locals with no previous acting experience. According to an article published in LA Mirror-News in Nov 1959, Kazan sparked a controversy in Cleveland after he hired extras from a slum known as “Gum Hollow” to play Depression-era Southerners. A number of prominent townspeople were angered by Kazan’s casting choice and allegedly claimed that the “white trash” of Gum Hollow did not accurately depict the area’s Depression unemployed. Kazan reportedly had to reshoot a few scenes, this time using “respectable, legitimate unemployed” in place of the “squatters.” According to information in the production file on the film in the AMPAS Library, during filming, Remick’s husband, television producer William Colleran, was in a serious auto accident and Remick returned to Los Angeles, causing production to shut down for one week. That delay, coupled with bad weather, put the shoot one month behind schedule.

Wild River received a number of positive reviews and was voted eighth runner-up for best picture of 1960 by the National Board of Review. A number of critics, however, felt that the romantic plot distracted viewers from the film’s powerful social themes, while the HR review declared that Wild River’s exploration of racial conflict “put the real story out of focus.” Other reviewers focused their criticism on Clift, with Films in Review declaring that Clift was “no longer capable of acting” and that “his tense form and visage devitalize[d] every scene he [was] in.” In his memoirs, Kazan termed the film a commercial “disaster” and placed part of the blame for its poor showing at the box office on Twentieth Century-Fox, which, Kazan alleged, did not distribute the film widely and pulled it too quickly from the theaters. Nevertheless, the film remained one of Kazan’s favorites and has received praise from modern critics, one of whom termed it Kazan’s “finest and deepest film.”

According to a modern source, Kazan’s earliest inspiration for Wild River came after a visit to Tennessee in the mid-thirties and a stint working for the Department of Agriculture in 1941. In his autobiography, Kazan stated that he had planned for many years to make a film which would be “an homage to the New Deal,” but that by the time he began working on the script, he had developed sympathy for the anti-progress stance represented by the character of Ella Garth, making Wild River his most ambivalent film in terms of its treatment of political and moral issues. A modern source reports that Kazan wanted Marlon Brando for the male lead, but he was unavailable. Kazan, who had directed Clift in a 1942 production of the play The Skin of Our Teeth, was at first adamently opposed to hiring Clift because of the actor’s drinking problem. Clift reportedly promised Kazan that he would stay sober for the duration of the shoot and he was accompanied to Tennessee by a secretary assigned to keep an eye on him. With the exception of one brief binge near the end of production, reported Kazan, Clift kept his promise.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely fascinating. Thanks.

LikeLike