I kept waiting for Deborah Kerr to turn up and it was a good 20 minutes before I realized that the actress had so immersed herself in the dowdy Ida Carmody that she was turning in what would be recognized as an Oscar-nominated performance. I was less convinced by Robert Mitchum’s Oirish accent but after a time, he, too, buried his normal screen persona under a feckless wanderer. And I was expecting some meaningful point-making stuff from director Fred Zinnemann given he had nursed home such purposeful features as High Noon (1952), From Here to Eternity (1953), A Hatful of Rain (1957) and The Nun’s Story (1959) and would soon be heading back in that virtue-signalling direction with Behold a Pale Horse (1964) and A Man for All Seasons (1966). However, like Day of the Jackal (1973), though for other reasons, this is very much an outlier in the Zinnemann portfolio.

It’s groundbreaking work from the stars. In the first place, Deborah Kerr does the unthinkable for a star of her magnitude – five Oscar nominations so far and a string of hits including From Here to Eternity, The Proud and the Profane (1955) opposite William Holden, The King and I (1956) top-billed ahead of Yul Brynner, An Affair to Remember (1957) opposite Cary Grant and Heaven Knows, Mr Allison (1958) leading Robert Mitchum a merry dance. Here, she is shorn of make-up. Her freckles are everywhere and her cheekbones look as if they are there from hunger not for reasons of fashion. These days, that down-to-the-wire approach would suggest an actress desperately trying to revive her career – Demi Moore in The Substance (2024) or Pamela Anderson in The Last Showgirl (2024) – rather than a star at the top of her game.

Robert Mitchum, too, dumps his screen persona, and provides his most relaxed and naturalistic performance.

The story is pretty straightforward. Ida wants to settle down, husband Paddy (Robert Mitchum), a born drifter, does not. Paddy enjoys drinking and gambling and wandering through the Australian Outback and ekes out enough as a drover to keep them solvent. The plot, therefore, is episodic. But what could have been a series of loosely-linked sequences is held together by a concentration of the reality of an existence revolving around sheep – droving, shearing, rearing – and trundling along in a horse-drawn caravan, putting up a tent at night, cooking over an open fire, other aspects bordering on the primitive. You can be sure that every minor triumph will be torpedoed.

You could be forgiven for thinking that Wyler had set out to make a western what with the preponderance of sweeping location. Make it sheep instead of cattle and you have Red River (1948) in a minor key with the usual shenanigans once the drover makes his destination.

Livening up proceedings are equally responsibility-resistant itinerant Rupert Venneker (Peter Ustinov), whose more basic skills including pugilism belie his posh accent, and innkeeper Mrs Firth (Glynis Johns) who makes a good stab at trying to hold onto him.

The bulk of the emotion plays through the eyes of Ida, desperately trying to save up enough money to buy a house. A bushfire that temporarily separates the couple unexpectedly acts to strengthen their relationship. While Ida is helping deliver a baby, Frank is getting roaring drunk. The tension between the pair is also a metaphor for growing civilization out of a wilderness, the men who tamed the land becoming redundant, a new educated class taking over. Ida wants to be settled to provide her ambitious son Sean (Michael Anderson Jr) with an education as much as she doesn’t want to be a traveller in her old age.

Offers much about a civilization in the making still relying on the old-timers to put in the hard yards while the guys doing all the work don’t have the sense to seek greater or more stable reward. What’s life if it doesn’t go wrong once in a while? Freedom is its own reward. As Paddy points out, he has no restrictions, the entirety of Australia is his bailiwick.

Wyler makes much of what he’s got, the tensions between the couple undercutting the strength of their affection for each other, and just when it looks as if Ida has got her way Paddy manages to cut loose and destroy her dreams.

There’s drama a-plenty, not just the terrifying bushfire, but a pretty engrossing horse race or two. Paddy’s idea of heaven is to hold court in a saloon singing old Irish songs. Sometimes Ida has little but heartbreak to nurse her along.

And while the various episodes make it a tidy drama, really it’s what one critic described as “a no-story movie – an observation of life” and in that regard more concerned with fallibility and vulnerability. Had it been made by a European director, it would remain one of the most talked-about movies of the decade.

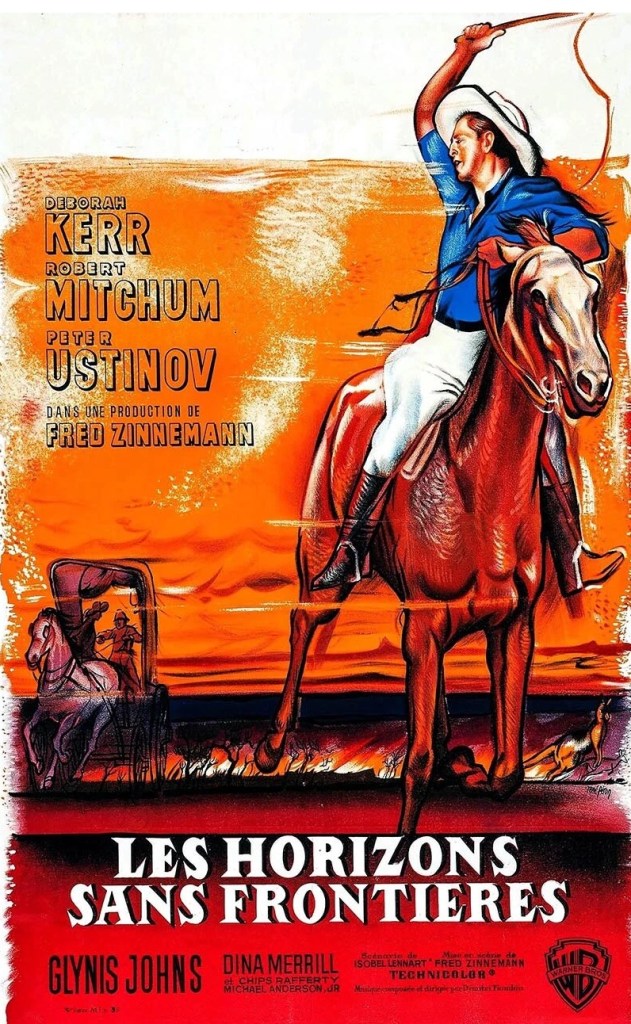

Wyler keeps up a tidy pace. Deborah Kerr (The Arrangement, 1969) steals the show and her peers agreed, putting her up for an Oscar, but it was a close-run thing because Glynis Johns (The Cabinet of Caligari, 1962) was also nominated. Peter Ustinov (Topkapi, 1964) was equally impressive, as was Robert Mitchum (El Dorado, 1967). Wyler was also nominated as was screenwriter Isobel Lennart (Fitzwilly / Fitzwilly Strikes Back, 1967) adapting the Jon Cleary bestseller.

I caught this on Amazon Prime.

Thoroughly involving.

Such a fine film in all respects.

For you:

“Although most reviews state that the running time is 133 minutes, the film’s copyright record and the NYT review list the duration as 141 minutes. The studio’s production notes for The Sundowners report that portions of folk songs “Lime Juice Tub,” “The Overlanders” and “Moreton Bay” were sung or played in the pub scenes.

Although a 6 Dec 1954 HR news item reported that producer Joseph Kaufman had taken an option on the Jon Cleary novel, his contribution to the final film, if any, has not been determined. According to a Dec 1959 NYT article, producer-director Fred Zinnemann’s inspiration to film The Sundowners came from lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II’s Tasmanian-born wife Dorothy, who urged him to make a film about Australia, a country that had rarely been featured in international films. Mrs. Hammerstein sent Zinnemann and his wife books with an Australian setting, among them, Cleary’s The Sundowners. After settling on The Sundowners, Zinnemann had to convince Warner Bros. to shoot the film in Australia, rather than a less expensive location site, such as Arizona or California. Eventually, according to Zinnemann’s autobiography, Jack Warner agreed to “follow the production pattern” of the successful Warner Bros. film The Nun’s Story (See Entry), by basing the film in London, and allowing some exteriors to be shot in Australia.

According to a May 1957 HR news item, Zinnemann was planning to produce and direct the film under his F.R.Z. Company and signed Aaron Spelling to write the screenplay. Although an Aug 1957 HR news item stated that Spelling would write the second draft of The Sundowners, according to Zinnemann’s autobiography, Spelling was replaced by Isobel Lennart.

HR production charts add Max Obiston and Mercia Barden to the cast, and HR news items add the following actors to the cast: Barbara Llewellyn, Gerry Duggan, Leonard Teale, Peter Carver, Ken Broadbent, John Fegan, Gwen Plumb, John Tate, Alex Kelleway, Jackie Knott, Frank Taylor, Robert Leach, Cliff Neat, Betty Lucas and Mavis Magnamara. None of the above-named actors’ appearance in the film has been confirmed. Although a Sep 1959 HR news item adds Lionel Jefferies to the cast, he did not appear in the film.

In an Oct 1959 LAT article, Zinnemann’s wife Renee stated that she played a nun at the railway station. Although she is too far away to be identified, two nuns appear in the sequence depicting the arrival of the “Carmodys” and “Rupert Venneker” in Cawndilla. A modern source adds Ray Barrett and Alister Williamson to the cast. Sixteen-year-old Michael Anderson, Jr., who portrayed “Sean,” was the son of noted British producer and director Michael Anderson, and had appeared previously in British films and television shows.

According to Zinnemann’s autobiography, champion jockey Neville Sellwood was Anderson’s horse riding double. Modern sources add the following crew members: Robert Lennard and Gloria Payten (Casting), Keith Batten (Sd mixer), Skeets Kelly (2d unit dir of photog), Gerry Fisher and Nicolas Roeg (Cam op), Elaine Schreyeck (Cont) and Ron Whelan (Loc mgr).

The film’s production notes state that interiors were shot at Associated British Pictures Corp. studios iin Elstree, England and exteriors were shot in Australia at Cooma, Nimmitabel and Jindabyne of New South Wales and in Port Augusta, Whyalla, Quorn, Iron Knob, Hawker and Carriewerloo in South Australia. The Sundowners was shot in a 1.85:1 frame ratio, because, according to Apr and May 1959 HR news items, Zinnemann believed that the large screen process did not “adapt to closeup work.”

The Sundowners received six Academy Award nominations: The film was nominated for Best Picture and Zinnemann was nominated for Best Director, but in both cases lost to United Artists’ The Apartment. Deborah Kerr and Glynis Johns were nominated for Best Actress and Best Supporting Actress, respectively, but lost to Elizabeth Taylor in Butterfield 8 and Shirley Jones in Elmer Gantry. The Sundowners was also nominated for Best Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium, but lost again to Elmer Gantry (see entries above for winning films).

Kerr and Mitchum appeared together in two other films, the 1957 Twentieth Century-Fox film, Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison, which was directed by John Huston (see above), and the 1961 Universal film The Grass is Greener, which was directed by Stanley Donen (see AFI Catalog of Feature Films, 1961-70). They also appeared together in the 1985 television movie, Reunion at Fairborough, which was directed by Herbert Wise.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Am doing a Behind the Scenes tomorrow.

LikeLike