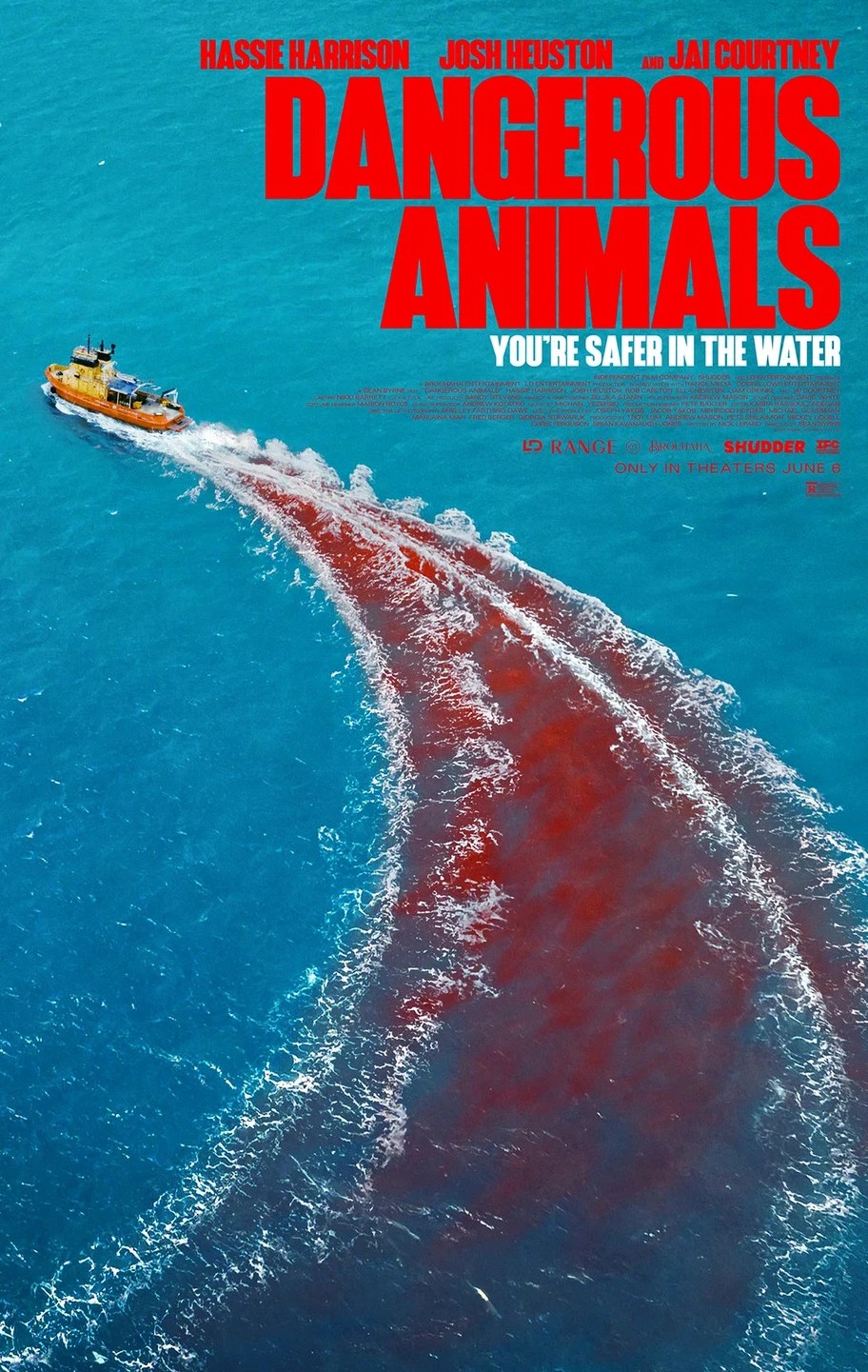

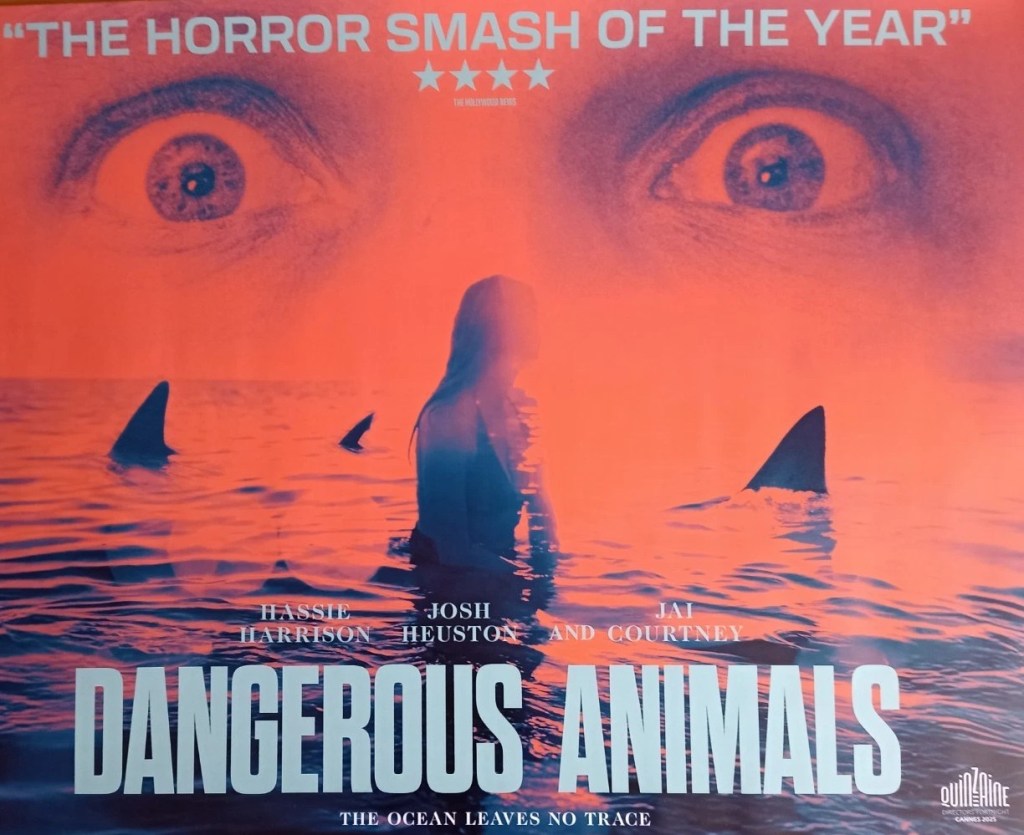

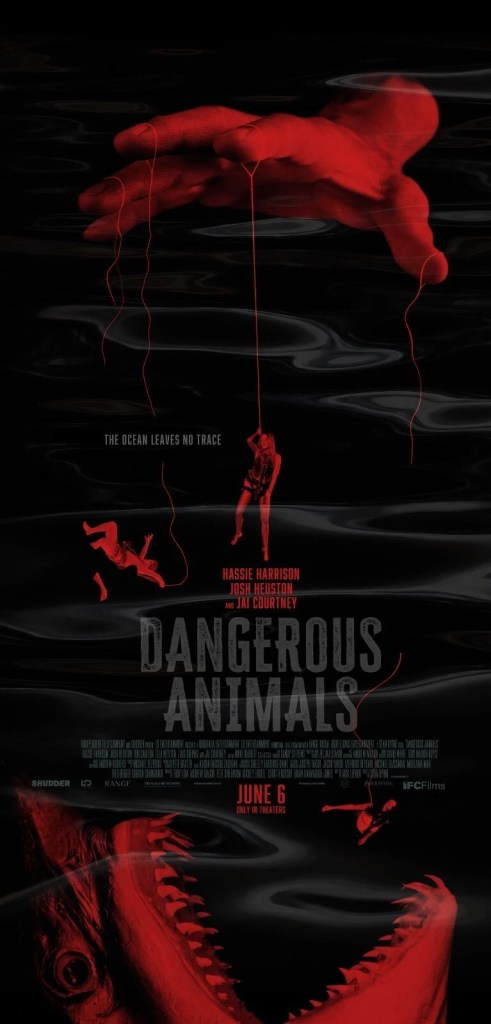

Steven Spielberg made his reputation dangling human bait to sharks and audiences lapped it up. I’m surprised it’s taken this long for a psychotic serial killer to understand the visceral thrill of watching victims die screaming as they are torn apart by sharks and churn up the sea in a froth of blood and guts. As you know I’m partial to a sharkfest and though this isn’t on the same epic scale in terms of destruction as Sharks under Paris (2024), given I was pretty fed up watching the dire Ballerina (let’s hope she’s excommunicated from the John Wick universe), I toddled off to see this without much in the way of expectation.

It’s pretty much in the Old Dark House line of horror pictures, good-looking young men and women imprisoned by a nutcase of the intelligent version of the species that recently surfaced in Heretic (2024). Aussie boat skipper Tucker (Jai Courtney) has a legitimate business taking tourists out shark-watching in a cage. And he’s got a side hustle in picking up vulnerable tourists – on gap years and the like or trying to escape the confines of the past or hiding out from consequence. He either catches his unwitting prey on land or waits till they turn up on his boat singly or in couples and not part of an organized tour from which their absence would be automatically noticed.

Heather (Ella Newton) and Greg (Liam Greinke) fall into the unannounced category. They get the shark experience but then Greg makes more intimate acquaintance with the predators after he’s knifed in the throat and tossed overboard.

Not only does Tucker like to watch he likes other victims to watch – someone dying. In full Spielberg mode he films the deaths. So he goes on the prowl for another victim, kidnapping the more sassy Zephyr (Hassie Harrison) in the middle of the night. She’s got a good deal more fight in her than the hapless Heather and manages to find a device to unlock the handcuffs chaining her to a bed, makes a makeshift shank from a broken piece of plastic and is adept at wielding a frying pan or harpoon or any other device that comes within range.

In between delivering homilies on the wonder of the shark, Tucker indulges in his dangling, the screaming Heather chopped to ribbons while Zephyr, strapped to the best seat in the house, is unwilling witness.

Luckily for Zephyr, she has smitten Moses (Josh Heuston), a one-night stand, and he has more detection skill than the cops who are not really interested in yet another beach bum who’s gone off without telling anyone. He tracks down the boat and invites himself to the party. Turns out between them they have more than a smattering of shark lore and when Josh is lowered into the water knows that the sharks will leave him alone if he doesn’t thrash about.

But drugged and chained up the pair have little chance of escape unless the doughty Zephyr goes full tilt escapologist boogie and gnaws off her thumb off to facilitate the cuffs slipping over her hand.

Unfortunately for her this picture is so full of twists there’s very little chance of a clean getaway and even when she makes it to the shore by swimming Tucker, thanks to a dinghy with an outboard motor, is on top of her.

It’s not as gruesome as it sounds, though you will want to avert your eyes when Zephyr starts gnawing on her thumb, and director Sean Byrne (The Devil’s Candy, 2015) emulates his idol Spielberg by turning less into more, ratcheting up the tension through anticipation and some terrific footage of marauding sharks. It helps that he doesn’t have a lascivious bone in his body, there’s no sexual assault, no drooling over half-naked women, no wet t-shirt nonsense.

Hassie Harrison (Yellowstone, 2020-2024) is the latest in a bunch of feisty women who refuse to conform to the scream queen norm. Jai Courtney (The Suicide Squad, 2021) is exceptionally creepy as the learned soft-spoken psychopath. Written by Nick Leppard in his debut.

Sean Byrne knows how to turn the screws.