A great movie is more than the sum of its parts. There’s something indefinable, something as they used to say “in the ether”, or “hits the zeitgeist” or, more aptly “hits the spot” because the area in question can never be defined, yet somehow we know it’s there. A writer from several generations past came up with “only connect.” And that’s a pretty food summation. Audiences are not really interested in movies that connect with critics – we’ve been served up too much dross too often to trust critics, Anora (2024) a recent case in point. When movies scarcely drop any percentage of revenue at the box office in the second weekend it’s not because of a ramped-up advertising budget, but because movies have hit the spot, connected with audiences, acquired that elusive word-of-mouth quality. For sure, this is going to be an Oscar contender, which probably means all the fun will be knocked, as its supporters get all preachy on us about its importance as a social document.

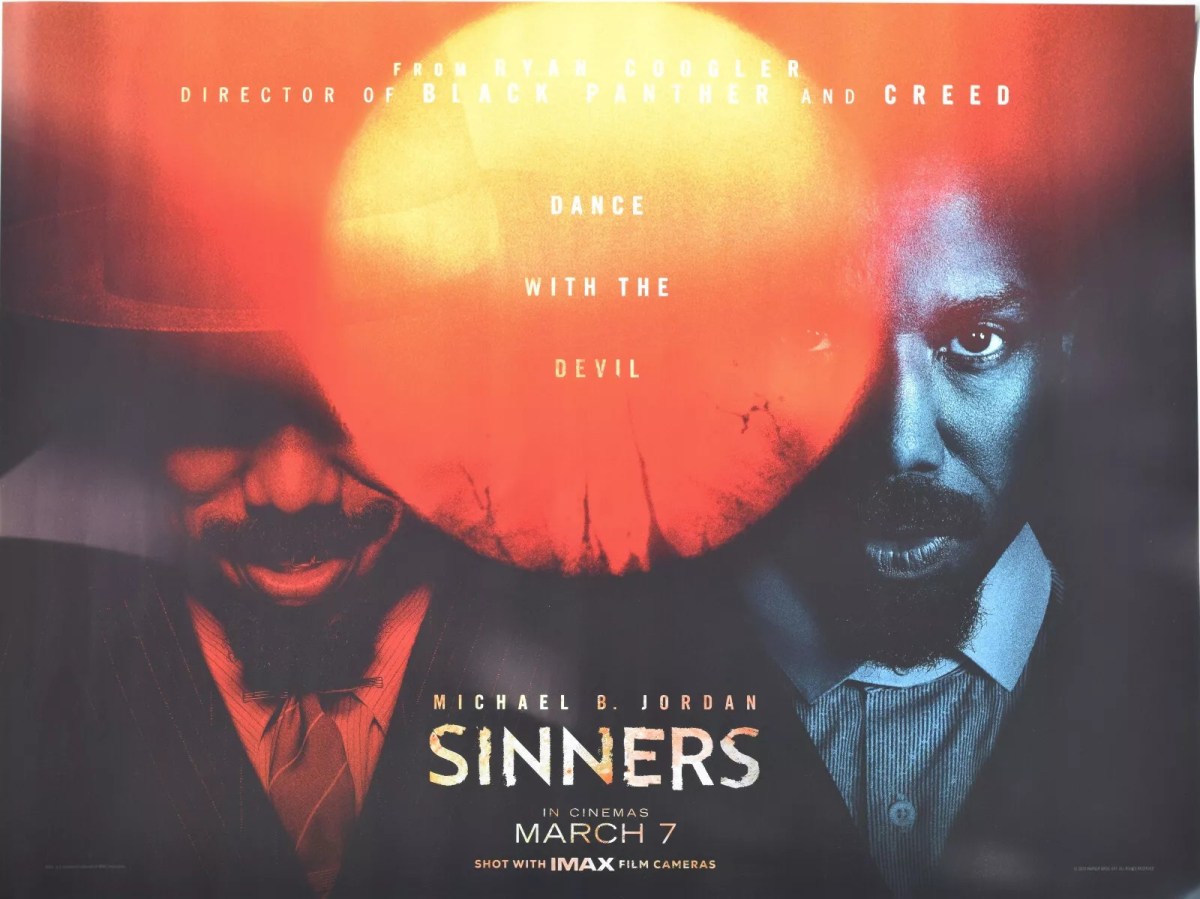

But a great movie comes from nowhere and sets up its own tent, creates its world, its own logic. There were gangster pictures before The Godfather (1972), westerns before The Searchers (1956) or Once Upon a Time in the West (1969) and sci fi before Avatar (2009) but what such pictures owe to their genres is derivative in a minor key. And so it here, Sinners takes the vampire movie and tosses it every which way but loose.

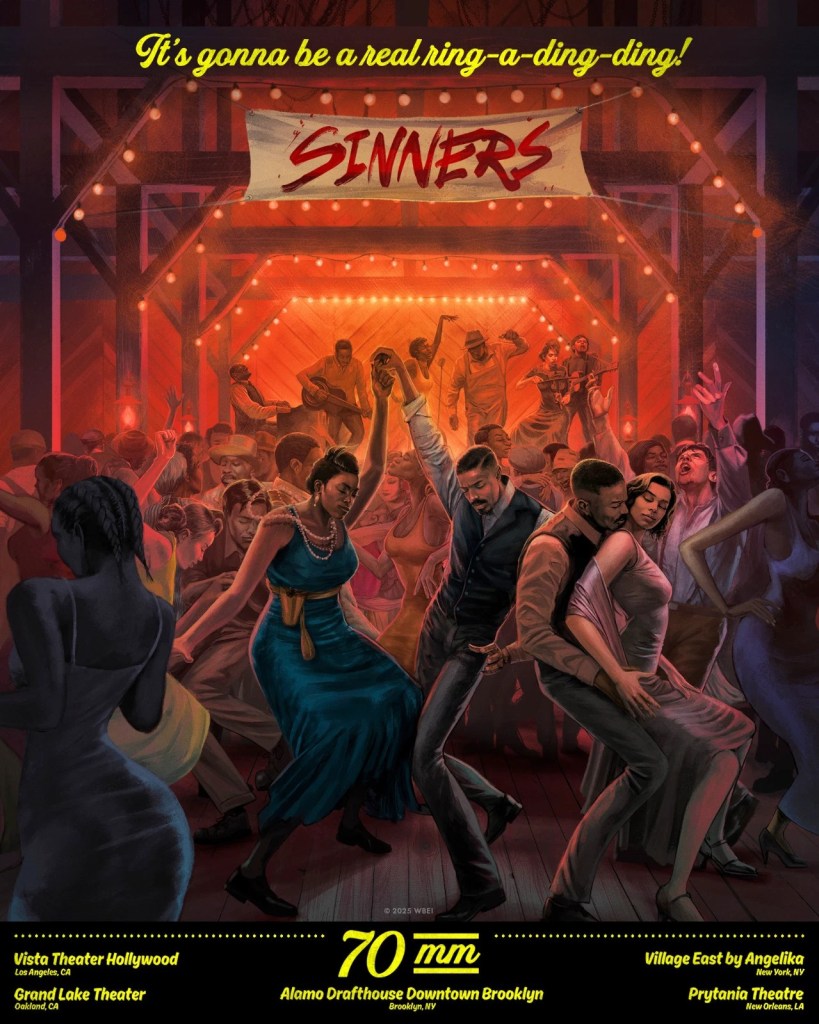

You got the blues, the most appealing vampires you’ll ever come across (and not in the svelte style of another game-changer, The Hunger, 1983), the need for community, the duping of the poor through religion, music than can summon up Heaven and Hell, raw sexuality, belonging, mothers, orphans, genius, cotton, a world where African Americans who fought for their country discovered their country didn’t want to fight for them, where the white man is going to take your money and then, for sport, kill you, and the plaintive despair of never feeling the warmth of the sun again as long as you live – which is forever. And connections – there’s myriad connections that will hit home.

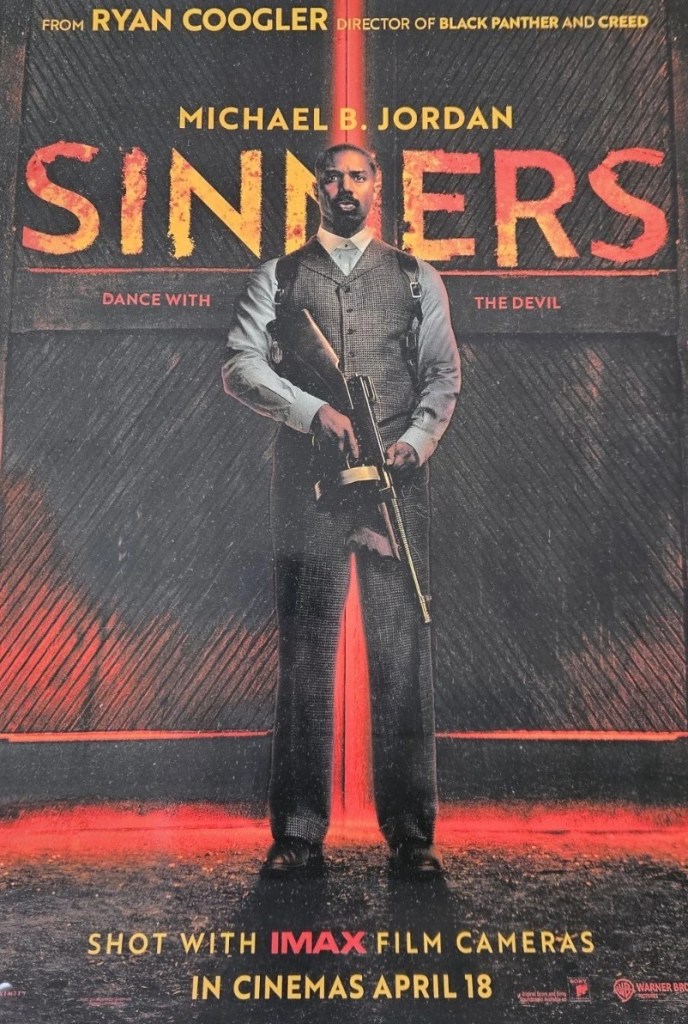

In fact, you might not be aware you’re watching a vampire movie for roughly the first half. You might imagine this is more akin to The Godfather Part II (1974) with gangsters trying to go straight. First World War veterans identical twins Smoke and Stack – I have to confess right till the credits I didn’t realize these were both played by Michael B. Jordan (Creed, 2015) – descend on a small southern town intending to make an honest buck from a dance hall, convinced they have acquired the necessary business acumen. The motley bunch enrolled in this endeavor include neophyte bluesman Sammie (Miles Caton), veteran alcoholic bluesman (Delroy Lindo), singer Pearline (Jayme Lawson), storekeepers Grace (Li Jun Li) and Bo (Yao), bouncer Cornbread (Omar Miller), Smoke’s estranged wife Annie (Wunmi Musaki), who has knowledge of the occult, and Stack’s ex-girlfriend Mary (Hailee Steinfeld). Coming a-calling is Irish immigrant Remmick (Jack O’Connell) recruiting new members for his vampire flock.

The movie doesn’t take flight so much in the unwinding of intertwined lives, or with the rocking action, as with two dance sequences that transcend anything you’ve seen before in the cinema, the first conjuring up music of the past, present and future, the second a routine by the vampires. Trying to save himself from vampires, Sammie begins reciting the Lord’s Prayer only to hear the sacred words echoed by the undead. A guitar is buried in Remmick’s head. And there’s a fascinating coda, if you wait through the credits.

Michael B. Jordan is the obvious pick, striding across both characterizations with immense aplomb (the Oscars will be calling) but Miles Caton in his debut, Delroy Lindo (Point Break, 2025), Hailee Stainfield (The Marvels, 2023), and especially the seductive blood-lusting Jack O’Connell (Ferrari, 2023).

Writer-director Ryan Coogler came of age with Creed and the Black Panther duo but this takes him into the stratosphere, a genuine original talent, not just with something to say but the visual smarts to match. He could have harked on a lot more. Too many worthy pictures have turned virtue-signaling into an art form, but one boring beyond belief. Coogler is much more subtle, he slips in his points.

But all the subtlety in the world wouldn’t count for a hill of beans if he couldn’t tell a story in way that connected big-time with the audience who wanted to tell their friends to go-see.