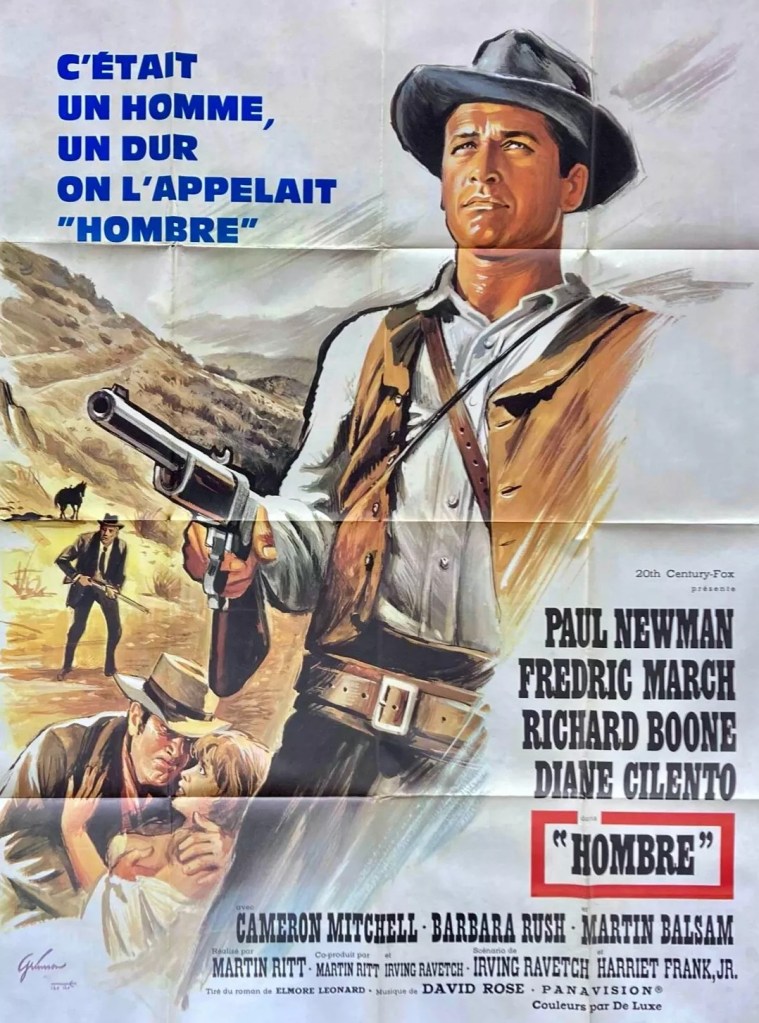

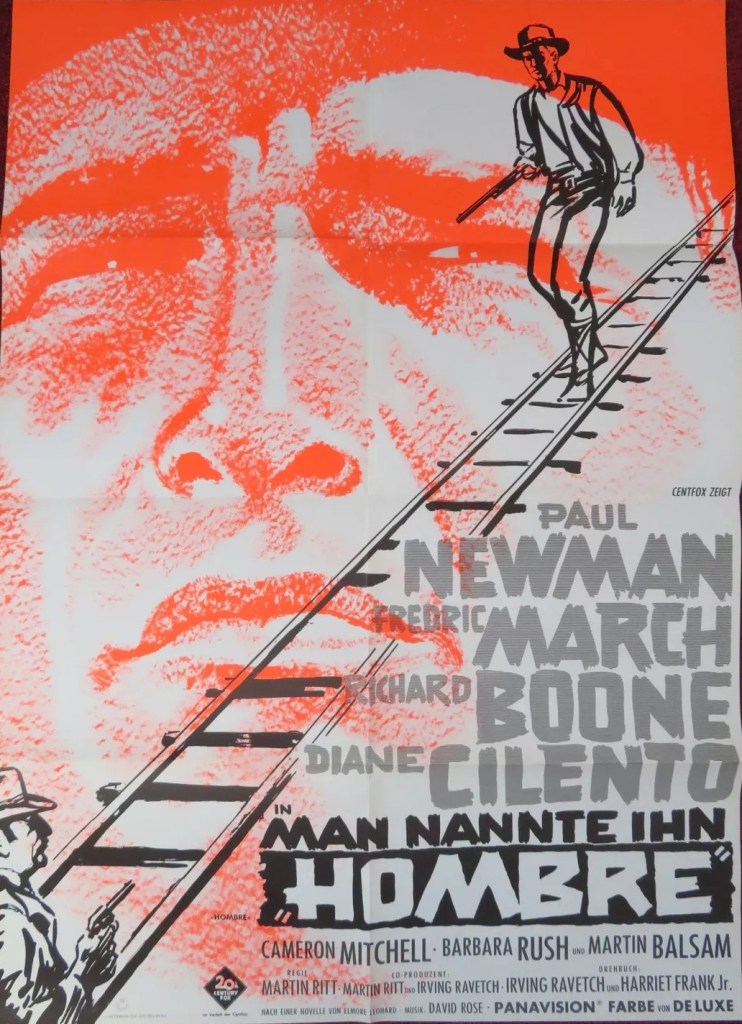

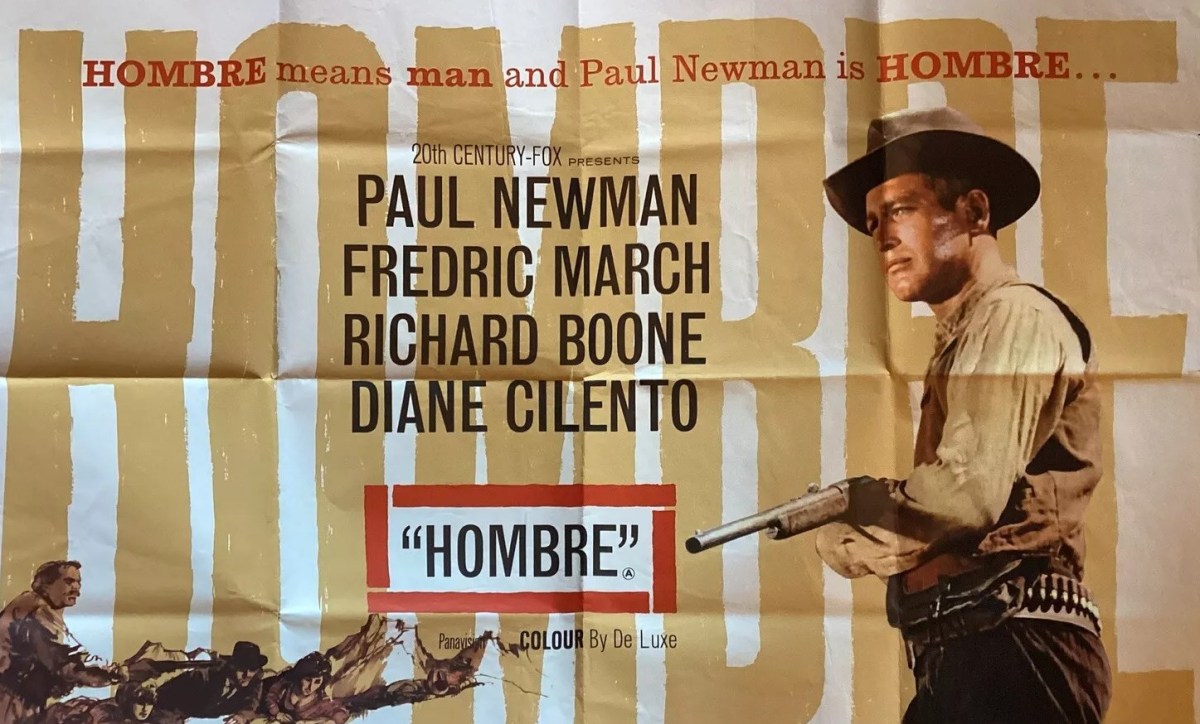

Shock beginning, shock ending. In between, while a rift on Stagecoach (1939/1966) – disparate bunch of passengers threatened by renegades – takes a revisionist slant on the western, with a tougher look at the corruption and flaws of the American Government’s policy to Native Americans. Helps, of course, if you have an actor as sensitive as Paul Newman making all your points.

The theme of the adopted or indigenous child raised by Native Americans peaked early on with John Ford’s The Searchers (1956) but John Huston made a play for similar territory in The Unforgiven (1960) and, somewhat unexpectedly, Andrew V. McLaglen makes it an important element of The Undefeated (1969).

This begins with a close-up of a very tanned (think George Hamilton) Paul Newman complete with long hair and bedecked in Native American costume. Apache-raised John Russell (Paul Newman) returns to his roots to claim an inheritance – a boarding house – after the death of his white father. That Russell is a pretty smart dude is shown in the opening sequence where he traps a herd of wild horses after tempting them to drink at a pool. He decides to sell the boarding house to buy more wild horses.

That puts him on a stagecoach with six other passengers – Jessie (Diane Cilento), the now out-of-work manager of the boarding house, retired Indian Agent Professor Favor (Fredric March) and haughty wife Audra (Barbara Rush), unhappily married youngsters Billy Lee (Peter Lazer) and Doris (Margaret Blye), and loud-mouthed cowboy Cicero (Richard Boone). Driving the coach is Mexican Henry (Martin Balsam).

Getting wind that outlaws might be on their trail, Henry takes a different route. But the cowboys still catch up and turns out Cicero is their leader. He takes Audra hostage, though she appears quite willing having tired of her much older husband, steals the thousands of dollars that the corrupt Favor has stolen from the Native Americans, and, also taking much of the available water, leaves the stranded passengers to die in the wilderness.

The passengers might have lucked out given Russell is acquainted with the terrain but they’ve upset the Apache by their overt racism, insisting he ride up with the driver rather than contaminate the coach interior. And the outlaws, having snatched the loot, and Cicero his female prize, should have galloped off into the distance and left it to lawmen to chase after them.

But Russell, faster on the uptake than anyone expects, manages to separate the gangsters from the money, forcing them to come after it. Russell wants the cash to alleviate the plight of starving Native Americans as was originally intended, but he has little interest in doing the “decent thing” and shepherding the others to safety. Ruthless to the point of callous, he nonetheless takes time out from surviving to educate the entitled passengers to the plight of his adopted people.

A fair chunk of the dialog is devoted to Russell explaining why he’s not going to do the decent thing and giving chapter and verse on the indignities inflicted on his people, and that alone would have given the picture narrative heft, especially as the corrupt Favor is more interesting in retrieving the money than his wife.

But in true western fashion, Russell is also a natural tactician and manages to pick off the outlaws when they come calling, impervious to the cries of Audra staked out in the blazing sun as bait. Eventually, against his better judgement, Russell gives in to the entreaties of Jessie and attempts to rescue the stricken women only to be cut down by the gunmen. I certainly didn’t expect that.

So, it’s both action and character-led drama. Paul Newman (The Prize, 1963) is superb (though not favored by an Oscar nod), especially his clipped diction, and oozing contempt with every glance, and the whiplash of his actions which is countered by shrewd judgement of circumstances. But Diane Cilento (Negatives, 1968) is also better than I’ve seen her, playing the foil to Newman, sassy enough to deal with him on a male-female level, but with sufficient depth to challenge his philosophy. Strike one, too, for Martin Balsam (Tora! Tora! Tora!, 1970) in a lower-keyed performance than was his norm. Richard Boone (Rio Conchos, 1964) and the oily Fredric March (Inherit the Wind, 1960) are too obvious as the bad guys. Representing the more calculating side of the female are Barbara Rush (The Bramble Bush, 1960) and movie debutant Margaret Blye.

The solid acting is matched by the direction of Martin Ritt (The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, 1965). Prone to preferring to make picture that make a point, he has his hands full here. But the intelligent screenplay by Irving Ravetch and Harriet Frank Jr. (Hud, 1963), adapting the Elmore Leonard novel, make the task easier, offsetting the potentially heavy tone with some salty dialog about sex and married life.

Thought-provoking without skimping on the action.

One of my favorite western movie. Martin Ritt is almost forgotten but he was such a great director.

LikeLiked by 1 person

He would be considered too serious these days but he had a very wide range. Generally, I enjoy his pictures and the opening long tracking shot of The Molly Maguires is amazing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Found this:

“During this time, Ritt began pre-production and set out to hire the supporting cast. Items in the 1 Nov 1965 and 11 Nov 1965 DV reported that Trini Lopez and Don Grady were in early negotiations to star, while 29 Dec 1965 Var and 6 Apr 1966 LAT briefs included Barry Sullivan and Alma Beltran among the cast. None appear in the final film. Janice Rule was originally signed as “Audra Favor,” but a 31 May 1966 LAT article explained that she requested to be relieved from the picture because she felt the character necessitated rewrites. A conflicting report in the 9 Mar 1966 Var claimed that this report was false, as Rule actually walked out during rehearsals due to problems over the “housing situation” on location. The same article named Dana Wynter as her replacement, but the role was filled by Barbara Rush, who previously worked with both Ritt and Newman in No Down Payment (1957, see entry) and The Young Philadelphians (1959, see entry). The 27 Apr 1966 Var stated that Martin Balsam received a $50,000 paycheck against the film’s total budget, which the 7 Feb 1966 DV estimated at $3.5 million.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating. Thanks.

LikeLike

Some More:

Principal photography began 28 Feb 1966 in Tucson, AZ, according to the 26 Apr 1966 LAT. Approximately two weeks later, an 11 Mar 1966 DV announced that the unit had completed work at the Old Tucson Studios movie studio-theme park and relocated to the Gold King Mine in Jerome, southeast of the city, while additional work took place at the Coronado National Forest. Shortly after, Newman fell ill with the flu, and a 6 Nov 1966 NYT article stated that he spent five days recuperating in the hospital. Additional problems arose when the 26 Apr 1966 DV reported that production had stalled again when Diane Cilento suffered a throat infection caused by a dust storm. NYT claimed that winds reached speeds of sixty miles per hour, and the temperatures often exceeded 100 degrees Fahrenheit. Defective color plates reportedly ruined an entire week’s worth of footage, and cameras ran out of film during the shooting of certain key sequences. The 1 Jun 1966 Var also detailed an incident in which Newman and company electrician Tommy Hayes saved Ritt from being hit by a 300-pound lamp when his camera dolly malfunctioned in the Santa Rita Mountains.

The 20 Apr 1966 Var figured that the production contributed $400,000 to the local Tucson economy, and the 2 Jun 1966 Los Angeles Sentinel stated that the cast and crew also participated in a benefit baseball game that raised money for the Tucson Camp for Underprivileged Children, and the Watts Happening Coffee House and American Theatre of Being, both located in the Watts-Compton neighborhood of Los Angeles, CA.

As a result of the complicated shooting conditions, production moved to Las Vegas, NV. According to an 8 Jun 1866 Var item, the unit set up headquarters at the Mint Hotel, but spent their days filming at Dry Lake near the town of Jean, NV. Although filming was expected to continue for at least another week, the 13 Jun 1966 DV announced that the remaining eighteen days would take place at the Fox studio backlot in Los Angeles. The NYT article indicated that additional scenes were shot at Bell Ranch in the Santa Susana Mountains of California. For the final few weeks, Joseph E. Rickards replaced assistant director William McGarry, who was forced to fulfill a prior commitment. In total, the original six-week shooting schedule was stretched out over nearly five months. The 30 Jun 1966 DV estimated that production of Hombre ran six weeks over schedule and $1 million over budget. Newman was reportedly compensated with an overtime pay rate of $75,000 per week.

A 20 Jul 1966 Var article revealed that Steven North, son of film composer Alex North, was offered a job as Ritt’s second assistant director on the project, but the Directors Guild of America (DGA) refused to hire him because he was not a member at the time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are a fount of fascinating information. Another fascinating background article. Thanks.

LikeLike