Contemporary audiences will be familiar with the jukebox picture. Moviegoers attending biopics of Queen or Elton John can be guaranteed a greatest hits package and if the narrative isn’t driven by problems facing rock superstars nobody is really bothered by an over-confected storyline such as Mamma Mia (and sequel) as long as the soundtrack is filled with beloved classics. On top of that we have the modern phenomenon of Event Cinema where cinemagoers pay to see a live performance, mostly plays, but Andre Rieu taking care of anyone who requires live music.

Song without End is more liberal than most when it comes to the music choices. As well as focusing on the tunes of Hungarian composer Franz Liszt, it also takes time out for snatches of Chopin or Wagner. These days a star like Dirk Bogarde would be a shoo-in for an Oscar nomination for all the training he put in to prove he could actually play the piano – and in demonic style – rather than showing him knocking out a couple of chords before cutting away to his face or any other shot of the piano except one involving his fingers.

And that’s both the plus and minus point of the movie. Plenty sequences of the maestro at the piano to satisfy the most ardent fan, plenty shots, too, in cutaway, of audiences, that element mostly boring until we are shown the rabid female fans who created the term “Lisztomania.” But the music comes at a price. Unless you are a big fan of the composer you’re faced with the same scene over and over again. Yes, he plays different compositions, and not always his own, and although the fingers move to different keys on the instrument, still it’s nothing but a guy sitting at a keyboard for ages.

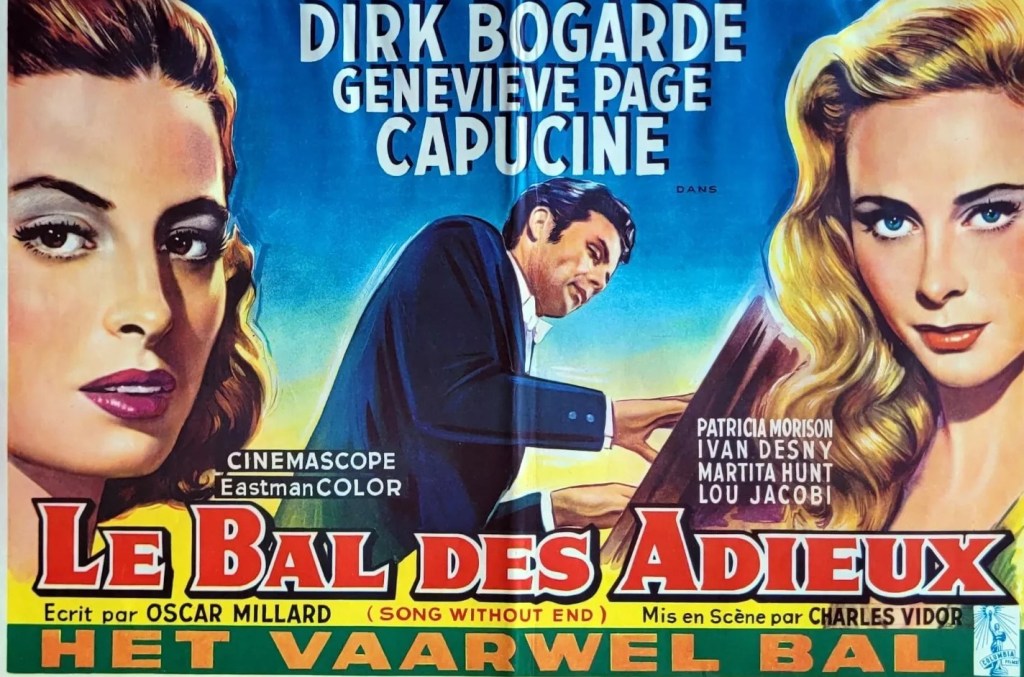

So, if the music does it for you, a joy. Otherwise, not so much going on or could be explored in any great depth at the time. Franz Liszt (Dirk Bogarde) was a bit of a lad – when the picture opens he’s living with married woman Marie (Genevieve Page), a countess, and is about to dump her for married Carolyne (Capucine), a Russian princess. Outside of his adultery, the main storyline is him making the transition from pianist to composer. And he helps along newcomer Richard Wagner (Lyndon Brook) – they became great friends until Wagner married Liszt’s daughter, though that’s outwith the movie’s remit.

But he’s something of a contradiction – zest for the high life with buddies Chopin (Alex Davion) and George Sand (Patricia Morison) countered by religious ideals (not shared, it transpires, by the countess). Liszt is very much the “artiste”, given to flouncing around, and having a hissy fit with the Czar of Russia for keeping him waiting. You could surmise that Tom Hulce modelled his portrayal of Mozart in Amadeus (1984) on this kind of charismatic character. Slap him in a pair of tight-fitting trousers, and given his good looks and flowing locks, and you’d have a modern day rock god. .

You’ll not be surprised to learn the movie gives a wide berth to the way he developed music; he was credited with several technical innovations. If you knew what you were looking for, probably you’d pick them out from his performances. He fair batters that piano as if trying to extract every last conceivable note.

This was something of a departure for British star Dirk Bogarde (Victim, 1961). His standard screen person was more prim, tight-lipped, straight-laced, repressed, so this feels like a monumental release, a cathartic moment. He’s certainly put in the work to come across as a proper piano player. The head-tossing and flouncing and heart-breaking is a doddle by comparison.

Columbia French starlet Capucine (The 7th Dawn, 1964), an MTA, made her debut with the kind of icy performance that became her fallback.

Columbia had been trying to make the picture for a decade and it nearly fell at the final hurdle. Director Charles Vidor, who had helmed A Song to Remember (1945) about Chopin, died soon after filming began. George Cukor (Justine, 1969) took over, adding trademark lushness and altering the ending, but, critically, giving Vidor sole credit. Oscar Millard (The Salzburg Connection, 1972) handled the screenplay.

Bogarde is pretty good, especially on the piano stool, and the music is terrific. So, ideal for music lovers not expecting much else. Bit of a let down for the general audience with not so much in way of narrative to get your teeth into.

Jukebox triumph.

Found this:

“The film’s working titles were Crescendo, A Magic Flame, The Franz Liszt Story The Life of Franz Liszt, and The Story of Franz Liszt. The film’s title card reads “Song Without End The Story of Franz Liszt.” The opening and closing cast credits differ slightly in order. The name of Georges Sands is misspelled as “George” in onscreen credits. George Cukor’s onscreen credit reads: “Grateful recognition of his generous contribution to this film is herewith extended to Mr. George Cukor.” Cukor took over the film’s direction from Charles Vidor when Vidor died on 4 Jun 1959 after completing about fifteen percent of the picture. The film’s onscreen credits acknowledge the works of the following composers following the words “the music of” George Frederick Handel, Frédéric Chopin, Ludwig van Beethoven, Richard Wagner, Felix Mendelssohn, Johann Sebastian Bach, Giuseppe Verdi, Niccolo Paganini and Robert Schumann. Selections of their works are heard interspersed throughout the film.

Franz Liszt (22 Oct 1811–31 Jul 1886) was a virtuoso pianist and composer born in Raiding, Hungary. A child prodigy, by the time he was middle-aged in the late 1840s, Liszt had created the musical form of the symphonic poem, a new and elastic single-movement form, which many subsequent composers embraced. As in the film, Liszt was involved in a relationship with Marie D’Agoult from 1835-1844. Unlike the film, however, they had three children, who were raised by Liszt’s mother after the couple’s relationship failed. In 1847, Liszt met Princess Carolyne and retired from the concert stage. In 1848, he settled in Weimar, where he developed the symphonic poem. Carolyne and Liszt attempted to marry in 1860, but on the eve of their wedding, their plans were thwarted by her unsubmitted divorce papers. Liszt , a devout Catholic, retired to Rome in 1861 and joined the Franciscan order in 1865.

According to a Dec 1956 LAEx news item, Columbia studio head Harry Cohn had wanted to make a film dealing with Liszt’s life since 1952. Starting in 1952, a number of writers attempted to tackle the thorny issues of Liszt’s life. In Jun 1952, a Var news item noted that Oscar Saul was to write the script and William Dieterle was to direct. A Dec 1952 LAT news item noted that Gina Kaus was to write the script. By Feb 1954, an LAEx^ news item announced that Jerry Wald, at that time an executive producer at Columbia, was preparing a story idea for the film and had hired Emmett Lavery, a Catholic, to write the script. In Apr 1954 a DV news item announced that Irving Shulman was to write the script and that Robert Cohn was to replace William Fadiman as producer.

A Dec 1955 HR news item noted that all of the scripts for the film would be turned over to Gottfried Reinhardt to produce. Although a May 1956 HR news item stated that Reinhardt was in Los Angeles to confer with Cohn over the completed script, an Oct 1956 HR news item noted that Columbia had hired Andrew Solt to write the screenplay. According to information contained in the film’s file in the MPAA/PCA Collection at the AMPAS Library, from Mar 1953-Sep 1954, Cohn entered into correspondence with Joseph Breen, head of the PCA, about how to portray Liszt’s controversial life. In those letters, Breen continually insisted that the idea of Liszt being “pure of heart” be deemphasized and stressed the need for proper technical advice in dealing with the film’s religious angles.

A Jun 1959 LAT news item noted that Victor Aller, the film’s musical coordinator, spent three weeks tutoring Dirk Bogarde on how to look as if he were playing the piano. Although the article stated that Sidney Kaye was to play Wagner, the musician was played by Lyndon Brook. According to a May 1958 LAEx news item, pianist Van Cliburn, the young American who had recently won the Tchaikovsky competition in Moscow, was considered to play the Liszt score. A Mar 1959 DV news item noted that Song Without End marked the first time that the L.A. Philharmonic was used to orchestrate a film. Modern sources add Ray Foster and Leola Wendorff to the cast.

An Aug 1959 HR news item noted that the film was shot in Vienna after the Soviet Union banned the producers from filming in Hungary, their location of choice. According to a May 1959 NYT news item, the court concert sequence was filmed at the Shonbrunn Palace in Vienna, the former summer residence of Emperor Franz Josef. The article noted that location shooting was also done at the Schloss Theatre and Esterhazy Castle in Vienna. Production material in the film’s production file at the AMPAS Library added that location shooting was also done at the Berndorf and Scala theaters in Vienna.

ISong Without End marked the screen debut of Capucine and the American film debut of Dirk Bogarde. The film won an Academy Award for Best Music, Scoring of a Motion Picture. According to a Jan 1961 DV news item, Joy Burns, the heir to writer and musician Theodore Kolline, sued Columbia for plagiarism, claiming that in 1946, Kolline had submitted three scripts to the studio based on the life of Liszt, and charging that Song Without End was based on those scripts. In Jan 1966, a Var news item noted that the court ruled in favor of the studio.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just fabulous stuff. You have amazing sources.

LikeLike