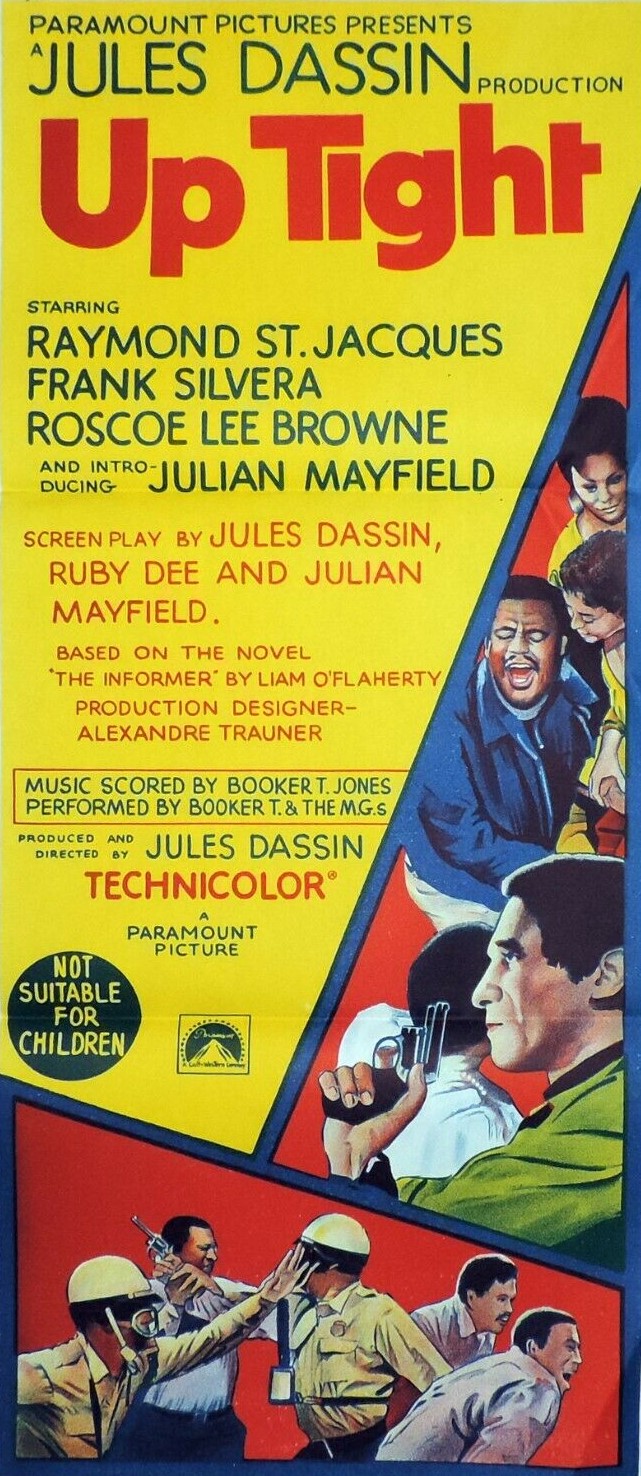

While a misplaced attempt to relocate John Ford’s Oscar-winning The Informer (1935) to Cleveland, Ohio, after the funeral of Martin Luther King, director Jules Dassin more than makes up for it with his exploration of black militancy and racial conflict. The basic story of unemployed alcoholic Tank (Julian Mayfield) trying to regain the favor of local activist committee led by B.G. (Raymond St Jacques) is less interesting than the revolutionary backdrop.

Dassin was suited to uncovering the seamy side of life having helmed film noirs Brute Force (1947) and The Naked City (1948) and while mostly concentrating on dramas he remained best-known for heist pictures Rififi (1955) and Topkapi (1964) so it was almost a given that this movie would feature a robbery. Tank was supposed to be part of a team, led by Johnny Wells (Max Julien), hijacking guns, but he’s too drunk to help, and during the robbery after a guard is killed the finger points at Johnny.

Assailed for his lack of maintenance by Laurie (Ruby Dee), mother of his kids, who subsists on welfare and prostitution, Tank considers informing on Johnny and picking up the $1,000 reward. So the story becomes a question of whether he will succumb to temptation.

But that’s really just a MacGuffin for an insight into the problems facing the poverty-stricken black population and the armed response many feel is the only way to resolve such issues. Several outstanding sequences depict the raw emotions of people trapped in this lifestyle. The opening scene, showing the funeral of Martin Luther King, became a clarion call for violence. Laurie is humiliated by the welfare officer. Police attempting to arrest Johnny are met with a fusillade of bottles.

The case for armed insurrection is made abundantly clear. The black population is continually oppressed, not just by police violence, but being told they lack the skills for a rewarding job. “When you’re born black, you’re born dead.” B.G. rejects the offer of assistance of white civil rights activists.

Not all the locals are underdogs. Clarence (Roscoe Lee Brown), with an apartment lined with bookshelves and wearing fine clothes, does very well out of his arrangements with the police and the black welfare officer clearly gets a kick out of his power to possibly disbar Laurie from receiving welfare.

While it might have proved more incendiary at the time, it’s impossible to miss the injustice portrayed. It was almost a wake-up call for the ruling authorities that there existed a growing underground force determined to achieve equality through violence if necessary. The idea of an organized group, rather than a shambolic mob, is the other clear message.

Any actor would balk at the prospect of matching the Oscar-winning performance of Victor McLaglen in the Ford original and surely no director would entrust the task to an inexperienced actor like Julian Mayfield whose only previous screen credit was a decade before in Virgin Island (1958). Mayfield finds it impossible to conjure up the pathos required and mostly appears as a bumbling fool.

This is despite the movie going out of its way to make Tank appear more sympathetic. He could easily claim he was blackmailed into informing by wealthy stool pigeon Clarence who holds compromising photographs. But, equally, the brotherhood, should it become aware of Clarence’s activities, would surely come down on him hard. Johnny absolves Tank of responsibility for not participating in the robbery, recognizes that while the man’s bulk was useful in the past, he lacks the mind-set for robbery. And he must stay away from Laurie otherwise she will lose her welfare.

But the rest of the cast is outstanding. Raymond St Jacques (If He Hollers, Let Him Go, 1968) stands supreme as an imposing Malcolm X figure. Roscoe Lee Brown (Topaz, 1969) is persuasive as confident gay informer. Activist Ruby Dee (The Incident, 1967) is good, too. And there is strong support from Frank Silvera (Guns of The Magnificent Seven, 1969), Max Julien, best known later for The Mack (1973), and in her movie debut Janet MacLachlan giving a hint of the acting skills that would win her an Oscar nomination for Maurie (1973)

Perhaps the most important element of the picture was the screenplay, a collaboration between Julian Mayfield, Ruby Dee and Jules Dassin, the involvement of the first two ensuring that the main targets were well and truly hit. With Dassin at the helm, the movie never loses its way, tension kept high by the hunt for Johnny, the personal dilemma of Tank and the various confrontations with B.G.

This is a movie that still stands up, not just because of its fearless delineating of the times, but from the suspicion that not enough has changed in the abject poverty to which so many are condemned.

Delivers a social sting.