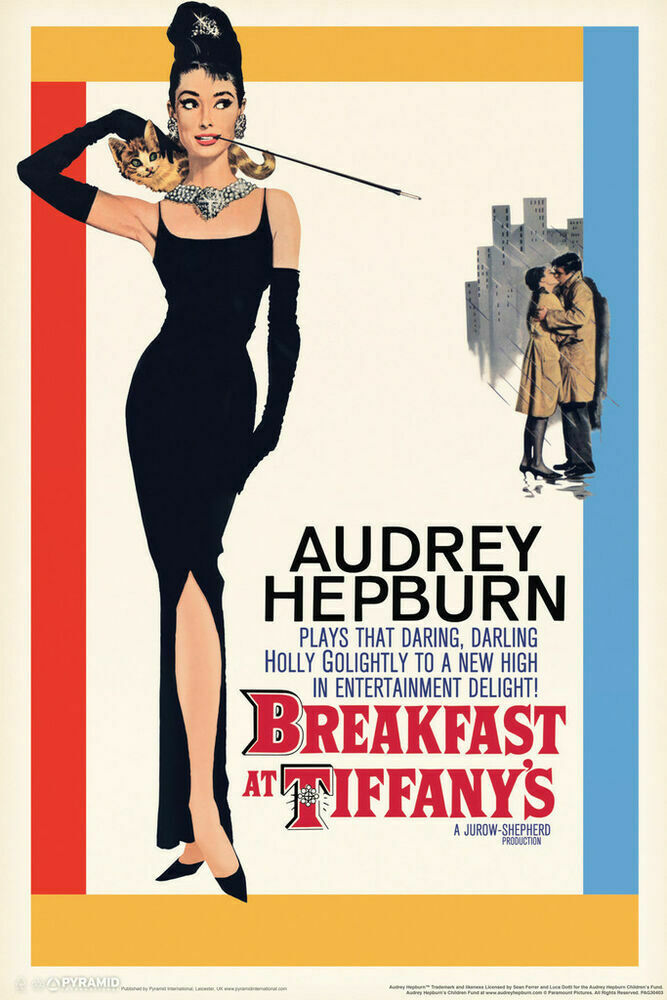

Reassessment sixty years on – and on the big screen, too – presents a darker picture bursting to get out of the confines of Hollywood gloss. Holly Golightly (Audrey Hepburn) is one of the most iconic characters ever to hit the screen. Her little black dress, hats, English drawl and elongated cigarette often get in the way of accepting the character within, the former hillbilly wild child who refuses to be owned or caged, her demand for independence constrained by her desire to marry into wealth for the supposed freedom that will bring, demands which clearly place a strain on her mental health.

Although only hinted at then, and more obvious now, she is willing to sell her body in a bid to save her soul. Paul Varjak (George Peppard), a gigolo, being kept, in some style I should add, with a walk-in wardrobe full of suits, by the nameless wealthy married woman Emily (Patricia Neal), is her male equivalent, a published writer whose promise does not pay the bills. The constructs both have created to hide from the realities of life are soon exposed.

There is much to adore here, not least Golightly’s ravishing outfits, her kookiness and endearing haplessness faced with an ordinary chore such as cooking, and a central section, where the couple try to buy something at Tiffanys on a budget of $10, introduce Holly to New York public library and boost items from a dime store, which fits neatly into the rom-com tradition.

Golightly’s income, which she can scarcely manage given her extravagant fashion expense, depends on a weekly $100 for delivering coded messages to gangster Sally in Sing Sing prison, and taking $50 for powder room expenses from every male who takes her out to dinner, not to mention the various sundries for which her wide range of companions will foot the bill.

Her sophisticated veneer fails to convince those whom she most needs to convince. Agent O.J. Berman (Martin Balsam) recognizes her as a phoney while potential marriage targets like Rusty Trawler (Stanley Adams) and Jose (Jose da Silva Pereira) either look elsewhere or see danger in association.

The appearance of her former husband Doc (Buddy Ebsen) casts light on a grim past, married at fourteen, expected to look after an existing family and her brother, and underscores the legend of her transformation. But the “mean reds” from which she suffers seem like ongoing depression, as life stubbornly refuses to conform to her dreams. Her inability to adopt to normality is dressed up as an early form of feminism, independence at its core, at a time when the vast bulk of women were dependent on men for financial and emotional security. Her strategy to gain such independence is of course dependent on duping independent unsuitable men into funding her lifestyle.

Of course, you could not get away with a film that concentrated on the coarser elements of her existence and few moviegoers would queue up for such a cinematic experience so it is a tribute to the skill of director Blake Edwards (Operation Petticoat, 1959), at that time primarily known for comedy, to find a way into the Truman Capote bestseller, adapted for the screen by George Axelrod (The Seven Year Itch, 1955), that does not compromise the material just to impose a Hollywood gloss. In other hands, the darker aspects of her relationships might have been completely extinguished in the pursuit of a fabulous character who wears fabulous clothes.

Audrey Hepburn (Two for the Road, 1967) is sensational in the role, truly captivating, endearing and fragile in equal measure, an extrovert suffering from self-doubt, but with manipulation a specialty, her inspired quirks lighting up the screen as much as the Givenchy little black dress. It’s her pivotal role of the decade, her characters thereafter splitting into the two sides of her Golightly persona, kooks with a bent for fashion, or conflicted women dealing with inner turmoil.

It’s a shame to say that, in making his movie debut, George Peppard probably pulled off his best performance, before he succumbed to the surliness that often appeared core to his acting. And there were some fine cameos. Buddy Ebsen revived his career and went on to become a television icon in The Beverley Hillbillies. The same held true for Patricia Neal in her first film in four years, paving the way for an Oscar-winning turn in Hud (1963). Martin Balsam (Psycho, 1960) produced another memorable character while John McGiver (Midnight Cowboy, 1969) possibly stole the supporting cast show with his turn as the Tiffany’s salesman.

On the downside, however, was the racist slant. Never mind that Mickey Rooney was a terrible choice to play a Japanese neighbor, his performance was an insult to the Japanese, the worst kind of stereotype.

The other plus of course was the theme song, “Moon River,” by Henry Mancini and Johnny mercer, which has become a classic, and in the film representing the wistful yearning elements of her character.

Found this:

“Paramount Pictures’ feature film adaptation of Truman Capote’s 1958 novella, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, was announced in a 12 Jan 1959 NYT news item, which stated that John Frankenheimer would direct for the producing team of Martin Jurow and Richard Shepherd, who had recently signed a three-year, six-picture deal with Paramount, as stated in the 8 Feb 1959 NYT. John Frankenheimer’s name received no mention in later sources, suggesting that his involvement was short-lived. Meanwhile, Audrey Hepburn’s casting as “Holly Golightly” was first announced in the 30 Jan 1959 DV, which stated that her participation “look[ed] certain.” A conflicting report in the 19 Feb 1959 DV indicated that Brigitte Bardot was under consideration for the role, and another in the 29 May 1959 DV named Marilyn Monroe as the top contender.

Sumner Locke Elliott was initially contracted to write the script, according to a news item in the 4 Feb 1959 DV. However, the 25 May 1959 DV stated that George Axelrod had been hired to write the screenplay, to be filmed later in the year. Elliott received no mention in the item, and was not credited in the final film. Axelrod’s script was completed by 14 Aug 1959, when DV reported that Shepherd and Jurow sent the finished screenplay to Marilyn Monroe, and other leading actress contenders including Shirley MacLaine, Joanne Woodward, Suzy Parker, and May Britt. Audrey Hepburn was named again as the “definite” star of the film in the 22 Apr 1960 LAT, which also reported that Blake Edwards was on board to direct. As mentioned in a 25 May 1960 NYT brief, Breakfast at Tiffany’s was set to be Hepburn’s first production after the birth of her first child with then husband Mel Ferrer, due that summer.

Hepburn eventually confessed in interviews that she had been reluctant to take on the role of Holly Golightly, and continued to question her involvement throughout filming. The actress was quoted in the 16 Jun 1961 NYT as saying, “This part called for an extroverted character. I am not an extrovert… It called for the kind of sophistication I find difficult. I did not think I had enough technique for the part.” In an interview in the 9 Oct 1960 NYT, Hepburn credited Blake Edwards with finally convincing her to take the part, and stated that his directing style emphasized a spontaneity that suited her talents. Nevertheless, Hepburn claimed she lost weight as a result of her anxiety during production.

Several actors were in contention to play Hepburn’s romantic interest, according to items in the 25 May 1960 DV, which noted that Jack Lemmon had been approached but was unavailable, and Robert Wagner was under consideration; and the 7 Jul 1960 LAT, which stated that Steve McQueen was reading for the role. George Peppard’s casting as “Paul Varjak” was announced the following week in the 14 Jul 1960 LAT. With the two lead actors in place, filming was expected to begin in Sep 1960.

The 11 May 1960 DV indicated that talent representative Bullets Durgom, who was in talks with producers regarding a role for his client, Eva Gabor, was unexpectedly approached to play fictional Hollywood agent “O. J. Berman.” Durgom was reportedly told that if he was not interested, filmmakers wanted another real-life talent agent, Irving Lazar, for the part. The character was ultimately played by actor Martin Balsam. Although Fernando Lamas was said to have been cast in the role of “José da Silva Pereira,” in a 27 May 1960 DV brief, the part went to José Luis de Vilallonga, who was credited simply as “Vilallonga.” Olivia de Havilland was also said to have been cast, with Tony Franciosa under consideration for a role, but neither received onscreen credit. Likewise, the 7 Jun 1960 DV named Dean Martin as a potential cast member; the 14 Sep 1960 DV stated that Kay Stevens, a comedienne-singer who recently performed a successful lounge act in Las Vegas, NV, was set to audition for the film; and the 8 Aug 1960 DV named Celeste Holm, Joan Fontaine, and Jane Greer as candidates for the “second female lead.” None of the aforementioned received credit in the final film. According to a 2 Dec 1960 DV article, actor James Garner had been offered a role in the picture but was unable to take it due to a force majeure clause exercised against him by Warner Bros. Pictures.

For the role of “Cat,” 300 felines were brought to an open casting call, as noted in a 5 Feb 1961 LAT item. The winning cat, Putney, appeared in location scenes shot in New York City, while a trained “movie feline” was used during West Coast shooting.

As noted in various contemporary sources, Truman Capote’s novel was altered significantly in the film adaptation. The 9 Oct 1960 NYT indicated that a love story and certain plot elements were added for commercial purposes. Holly Golightly’s promiscuity was also toned down, as was much of the dialogue found in the book. The 6 Jan 1961 NYT listed the following discrepancies in the film: Holly “no longer discusses her experiences with men in detail,” and is shown to be a “patroness of the arts,” a tactic devised by Axelrod to make her more likeable; Paul Varjak, originally “an aloof observer,” is presented as a romantic interest; and, while Capote’s novel offered an unhappy ending in which Holly Golightly disappeared, in the film she reunites with Varjak and her cat instead of fleeing from New York City. Despite the changes, Capote gave filmmakers his blessing, acknowledging that the screenplay was more “a creation of its own than an adaptation,” and that, most importantly, “Holly is still Holly, except once or twice.”

On 7 Jul 1960, DV reported that location scouting was underway in New York City. Two months later, Hepburn arrived in Los Angeles, CA, on 14 Sep 1960, according to that day’s issue of DV, and was set to report to Paramount Studios for costume fittings the next day. Principal photography began shortly thereafter, on 2 Oct 1960, with eight days of location shooting in New York City. The budget was estimated to be around $2 million, as cited in the 9 Oct 1960 NYT and 1 Nov 1960 DV.

Breakfast at Tiffany’s was the first film to shoot at the 123-year-old Tiffany’s jewelry store on Fifth Avenue, according to the 9 Oct 1960 NYT. Other Manhattan locations included the Mall in Central Park, the New York Women’s House of Detention on Tenth Street, a brownstone residence on the Upper East Side, and the exterior of the New York Public Library. Once the New York shoot was completed, cast and crew returned to Los Angeles for filming on the Paramount Studios lot, which was still underway as of 14 Dec 1960, when LAT reported that Hepburn’s six-month-old baby and his nurse were en route to Los Angeles from Hepburn’s home in Switzerland, for a set visit.

In late-Dec 1960, striptease dancer “Miss Beverly Hills,” who played the “Nightclub dancer,” was called back to set to perform additional striptease moves in a nightclub sequence. The 27 Dec 1960 DV explained that Blake Edwards planned to include the extended striptease sequence in an alternate version of the film for European release.

Principal photography ended on 3 Feb 1961, according to a DV item published that day. Martin Jurow’s partnership with Richard Shepherd dissolved upon completion of Breakfast at Tiffany’s and Love in a Goldfish Bowl (1961, see entry), as indicated in the 13 Dec 1960 DV. Jurow planned to vacation before taking up his new post as president of Famous Artists talent agency.

Two sneak previews were held on 7 Apr 1961 at the Golden Gate Theatre in San Francisco, CA, and on 8 Apr 1961 at an unnamed theater in Palo Alto, CA, according to the 10 Apr 1961 DV. The San Francisco preview was attended by Edwards, Hepburn, Mel Ferrer, Paramount production chief Martin Rackin, and composer Henry Mancini, who was also set to debut his score ahead of the film’s release, at a 23 Sep 1961 performance at the Hollywood Bowl amphitheater, as noted in the 1 Sep 1961 LAT. George Peppard engaged in an East Coast publicity tour in support of the film, according to an 11 Sep 1961 LAT item, after requesting time off from Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, with whom he was under contract. The tour included stops in New York City, Philadelphia, PA, and Boston, MA. In another promotional gimmick, Hepburn was slated to attend an actual breakast at Tiffany’s on Fifth Avenue, on her way home to Switzerland following the conclusion of her latest production, The Children’s Hour (1961, see entry), as noted in the 16 Aug 1961 DV.

A 5 Oct 1961 world premiere took place at Radio City Music Hall in New York City, as noted in the 6 Oct 1961 NYT review, with a stage show presentation featuring the New York Naval Shipyard Choir, singer Everett Morrison, the Corps de Ballet with dancer Istvan Rabosky, the Mathurins, and the Rockettes. The same presentation was reportedly offered at subsequent screenings at the venue. In Los Angeles, an invitation-only benefit premiere was held on 17 Oct 1961 at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, followed by a “WAIF Ball” benefitting the World Adoption International Fund. Screenings at Grauman’s Chinese, where the film was booked in an exclusive engagement, opened to the public the following day.

Critical reception was mixed. In a mostly favorable assessment, the 24 Sep 1961 LAT review singled out Mickey Rooney’s portrayal of the “buck-toothed Japanese photographer [Mr. Yunioshi]” as the worst supporting performance and termed it “inexcusable.” Although a separate review in the 19 Oct 1961 LAT called Rooney’s casting “a novelty but that’s about all,” the white actor’s depiction of Holly Golightly’s Asian neighbor gained notoriety over time, as an example of “yellowface,” the offensive portrayal of Asians by white actors. In a 14 Jan 1990 article, Newsday described Rooney’s characterization as “a grotesque parody,” and likened Breakfast at Tiffany’s to Gone with the Wind (1940), Stagecoach (1939), and Casablanca (1943, see entries), as a classic film that nonetheless reflected antiquated social attitudes and prejudices. A 13 Oct 2006 LAT item noted that a clip of Rooney in Breakfast at Tiffany’s was included in The Slanted Screen, a 2006 documentary about the racist portrayal of Asians in Hollywood films.

The picture achieved commercial success, with strong ticket sales in Los Angeles, as reported in a 16 Jan 1962 DV brief, citing a “smashing” $175,000 gross at twenty-five theaters. The 23 Oct 1962 DV listed Breakfast at Tiffany’s as one of 1961’s top thirteen first-run films in Los Angeles, with cumulative earnings of $244,838.

Audrey Hepburn received Best Actress accolades from Film Daily’s annual poll of an estimated 2,000 film reviewers, according to the 15 Jan 1962 NYT. Henry Mancini won an Academy Award for Music (Music score of a dramatic or comedy picture), and Mancini and lyricist Johnny Mercer’s “Moon River” won an Academy Award for Music (Song). Academy Award nominations also went to Audrey Hepburn for Best Actress; art directors Hal Pereira and Roland Anderson, and set decorators Sam Comer and Ray Moyer for Art Direction (Color); and George Axelrod for Writing (Screenplay based on material from another medium). Music from the film won the following five Grammy Awards: Record of the Year (“Moon River”); Song of the Year (“Moon River”); Best Performance by an Orchestra – for other than dancing (Breakfast at Tiffany’s); Best Arrangement (“Moon River”); and Best Soundtrack Album or Recording of Score from Motion Picture or Television. “Moon River” was ranked #4 on 100 Years…100 Songs, AFI’s 2004 list of the top movie songs of all time; and Breakfast at Tiffany’s was ranked #61 on 100 Years…100 Passions, AFI’s 2002 list of the greatest love stories of all time.

A 31 Aug 1961 NYT news brief stated that TransWorld Airline (TWA) planned to screen Breakfast at Tiffany’s as part of its newly launched “midair film projection” program, which had begun on 19 Jul 1961, and had included showings of By Love Possessed, Tammy Tell Me True, Romanoff and Juliet, The Naked Edge, Two Rode Together, and The Last Time I Saw Archie (1961, see entries).

Al Avalon appeared in a scene but was cut from the final film, according to an item in the 2 Sep 1961 LAT, which noted that Breakfast at Tiffany’s would have marked his theatrical motion picture debut.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fabulous. Amazing stuff. Thanks.

LikeLike