Ever since I’ve started writing this Blog, a film starring a female has taken pole position in the Annual Top 30. And this year is no exception though it has gone down to the wire with Sandy Dennis literally pipping John Wayne at the post. I was somewhat surprised to see some movies that featured on this list last year so prominent again. These include Stagecoach, Fireball XL5, Fraulein Doktor and The Sisters.

- Thank You Very Much/A Touch of Love (1969). Singleton Sandy Dennis comes to terms with pregnancy in London. Ian McKellen is the male lead.

- In Harm’s Way (1965). Otto Preminger war epic based around Pearl Harbor. John Wayne and Kirk Douglas duke it out.

- The Appointment (1969). Unusual Sidney Lumet drama set in Italy with Omar Sharif becoming mixed up with Anouk Aimee.

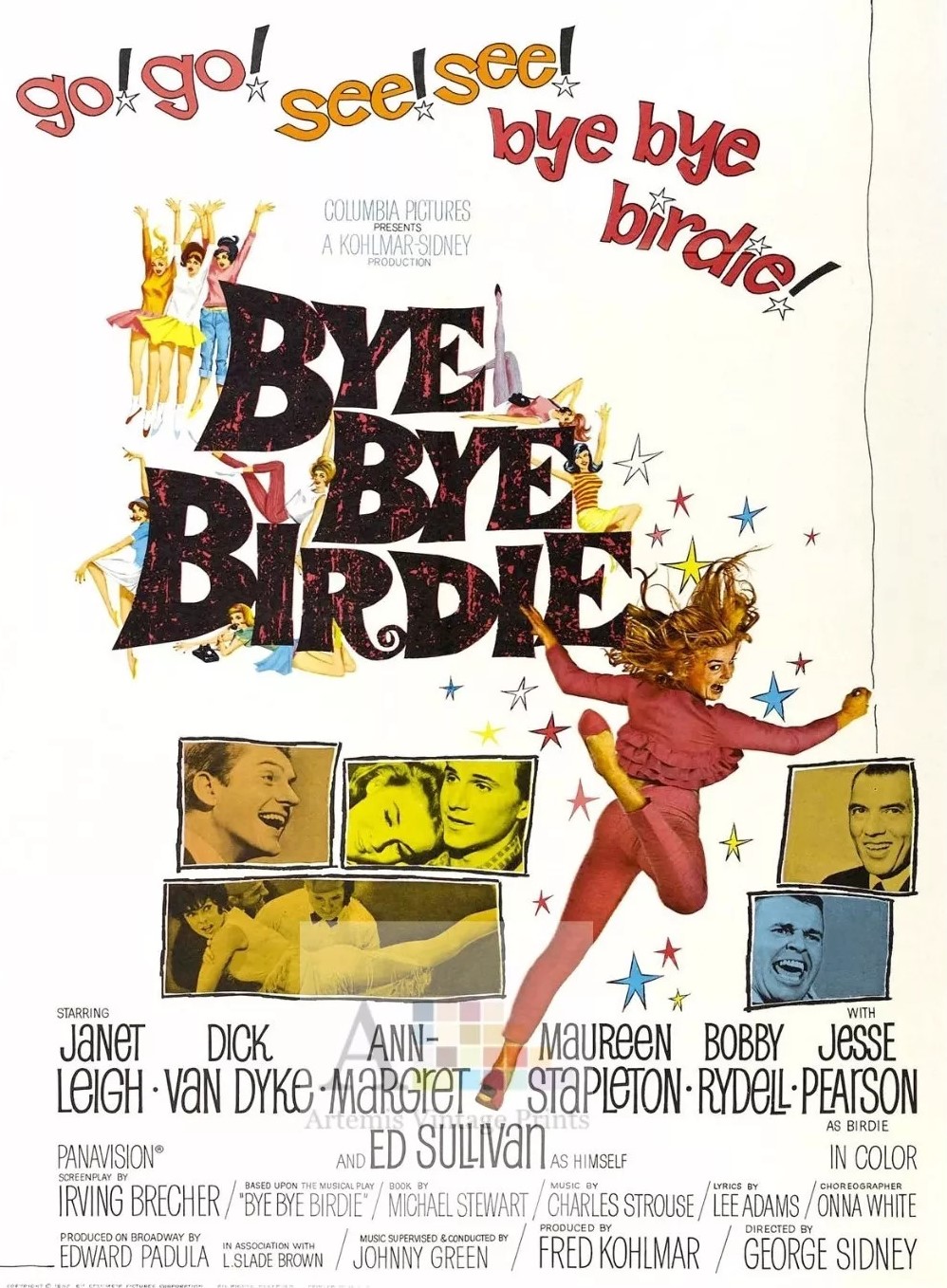

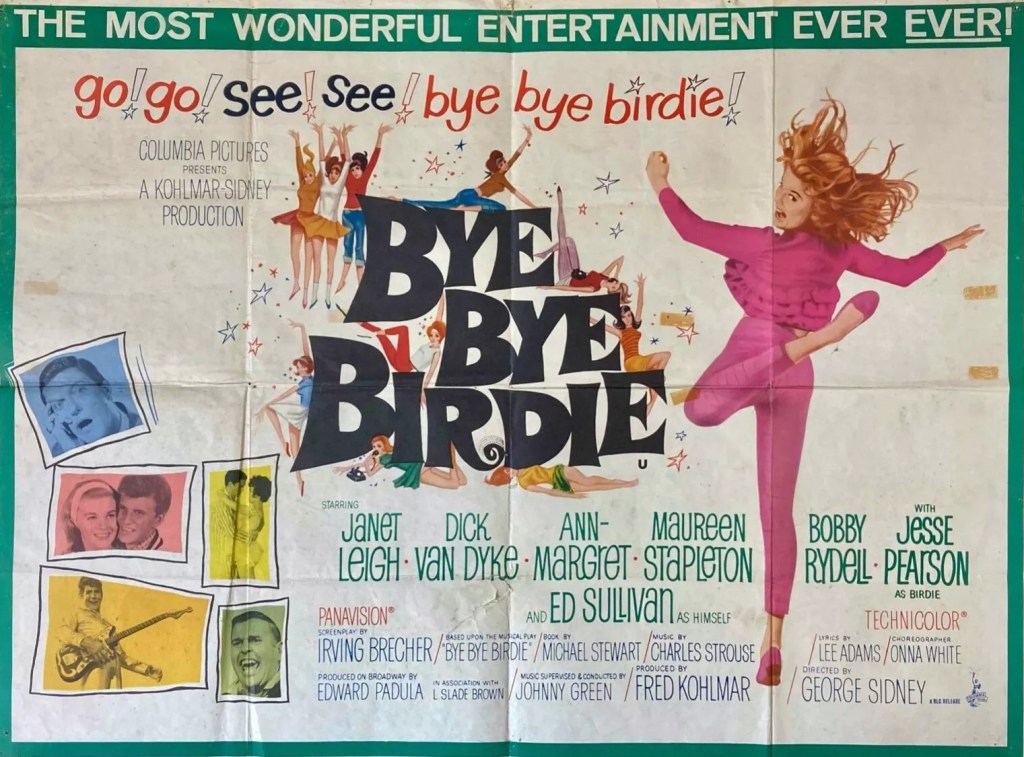

- Stagecoach (1966). There’s no stopping Ann-Margret. Interest remains high in remake of John Ford classic also starring Alex Cord and Bing Crosby.

- Young Cassidy (1965). Talking of John Ford, he was meant to direct this biopic of Irish playwright Sean O’Casey but took ill, leaving Jack Cardiff in charge. Rod Taylor and Julie Christie star.

- Diamond Head (1962). Charlton Heston as hypocritical racist landowner in Hawaii. Co-stars George Chakiris and Yvette Mimieux.

- Prehistoric Women/Slave Girls (1967). Martine Beswick is no Raquel Welch in One Million Years B.C. knock-off.

- The Chalk Garden (1964). Hayley Mills sheds her puppy fat as wild child brought to heel by Deborah Kerr as a governess with a secret past. Co-stars John Mills and Edith Evans. Directed by Ronald Neame.

- Fireball XL5. The colorised version of the Gerry and Sylvia Anderson futuristic classic British television series.

- Pharoah / Pharon (1966). Polish epic – religion vs state in ancient Egypt.

- Go Naked in the World (1961). Gina Lollobrigida finds out how difficult it is for a sex worker to fall in love. Fine Ernest Borgnine turn as a doting father.

- The Swinger (1966). Ann-Margret again. She sings, she dances – she writes? Who cares about a barmy plot when she shakes her booty.

- The Beekeeper (2024). Jason Statham kicks off a new action franchise with scintillating turn as black ops operative brought out of retirement. Jeremy Irons tries to keep the peace.

- La Belle Noiseuse (1991). French drama in which Jacques Rivette explores relationship between painter Michel Piccoli and model Emmanuelle Beart.

- Baby Love (1969). Teenager Linda Hayden unintentionally causing turmoil in dysfunctional middle class family in London.

- Pressure Point (1962). Psychiatrist Sidney Poitier coming to terms with racist patient Bobby Darin.

- Farewell Friend / Adieu L’Ami (1968). Charles Bronson had to go to France to find stardom in this heist thriller co-starring Alain Delon.

- Fraulein Doktor (1969). Suzy Kendall’s finest hour as World War One German spy outwitting Kenneth More.

- Immaculate (2024). Sydney Sweeney dons nun garb and encounters horror in Italian convent.

- The Count of Monte Cristo (2024). Splendid adaptation of the classic Dumas novel of a wrongly-imprisoned man seeking revenge.

- Fear No More (1961). Mentally disturbed Mala Powers mixed up in murder plot.

- Woman of Straw (1964). Gina Lollobrigida takes on Sean Connery in Hitchcockian thriller.

- Claudelle Inglish (1961). Thwarted bride Diane McBain exploits male desire in the Deep South.

- Carry On Up the Khyber (1968). Innuendo gets a cloak of satire as the team make light work of the British in India.

- The Trouble with Angels (1966). Hayley Mills again, another wild child, this time challenging Mother Superior Rosalind Russell in convent school.

- Lilith (1964). War veteran Warren Beatty bewitched by troubled Jean Seberg at a mental institution.

- The Sisters / My Sister, My Love (1969). Another French drama with Nathalie Delon and Susan Strasberg too tangled up with each other to bother with the likes of Giancarlo Giannini.

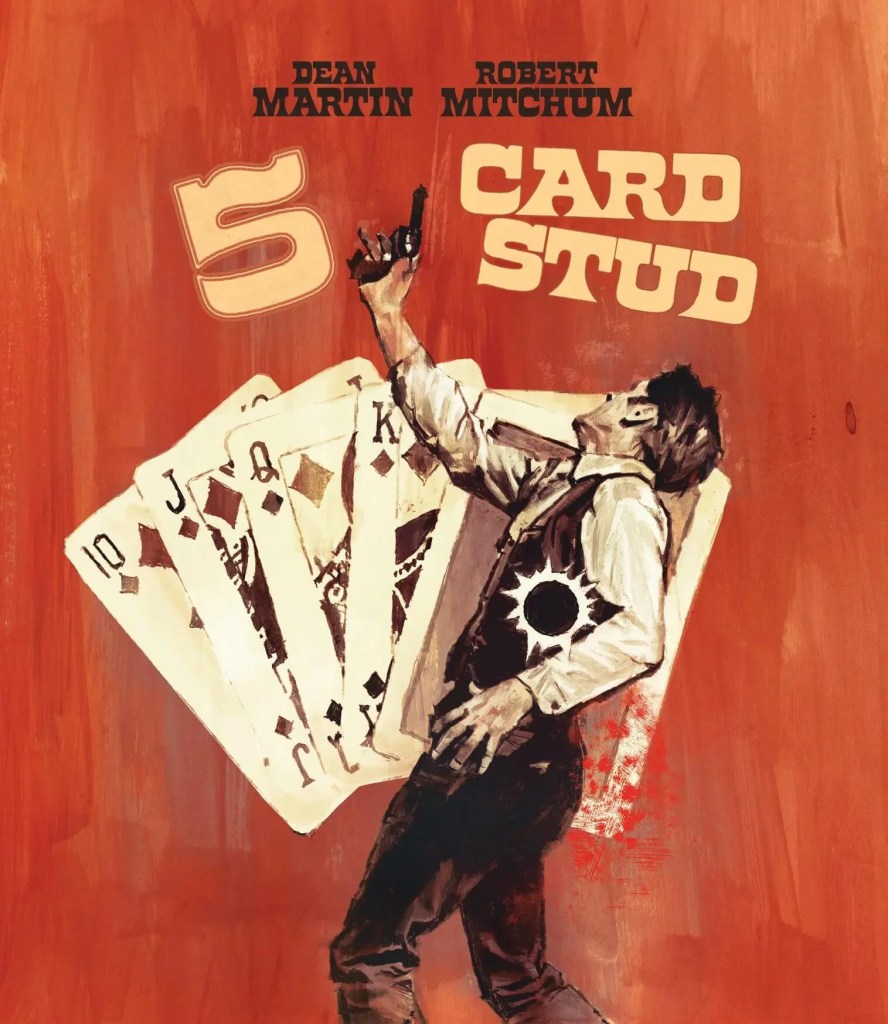

- Five Card Stud (1969). Poker player Dean Martin turns detective as the body count mushrooms in Henry Hathaway western co-starring Robert Mitchum and Inger Stevens.

- The Undefeated (1969). John Wayne chases defeated Confederate Rock Hudson into Mexico.

- Villain (1971). Heist thriller with Richard Burton and Ian McShane as bisexual gangsters.