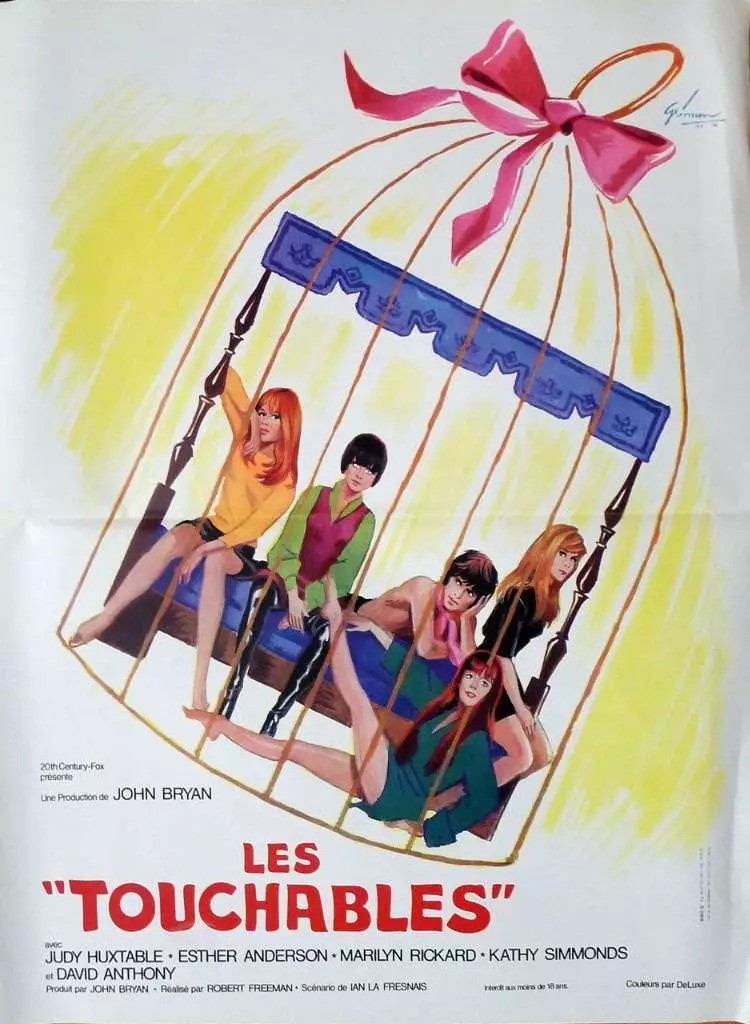

Take a giant bubble, yellow Mini, an abundance of mini-skirts, Michael Caine waxwork, one pop star, four models, a masked wrestler, nuns, table football, a pinball machine, a circular bed, various sunsets, a shotgun and a lass milking a fake cow. And what do you get? Not much? A dry run for Performance (1971), given Donald Cammell’s involvement, but otherwise a largely soporific feature hoping for redemption on the cult circuit. But with the unsavory subject matter, even with a proto-feminist outlook, that might struggle might to win approval from a contemporary audience.

Unlike Privilege (1967) it’s not saved by ironic comment on the music scene or even anything in the way of decent performances and looks more like an attempt to guy up the nascent careers of a bunch of young actresses and get by with a day-glo pop art sensibility. At no point are we invited to disapprove of the model quartet who decide, having tried out their kidnapping skills on a Michael Caine waxwork, that they might as well go the whole hog and abduct pop star Christian (David Anthony) and tie him to a bed and take their turns having their wicked way with him.

This is all purportedly acceptable stuff because a) it’s a gender switch and b) the poor pop singer is only too happy to escape the drudgery of making millions and not have to even consort with groupies and c) is presented as if he is thoroughly enjoying the whole experience. That is, if you ignore him being chloroformed, shot, and whacked over the head, then of course it’s all very pleasant.

Naturally, these being cunning wenches, they hide him in plain sight. Who would think to look for him in a giant transparent bubble?

Although drawn with villainous strokes, as were all the managers in Privilege who put unnecessary pressure on the pop star they have created, it’s hard to view Anthony’s upper class manager Twynyng (James Villiers) as a bad guy for wanting his safe return.

So what happens once the ladies take charge of their victim? Beyond sex, not much, playing with the various items mentioned, not even any jealousy rearing its ugly head, just the kind of cinematography that might well pass for advertising.

It’s hard to see what the point of it all was. Screenwriter Ian La Fresnais (The Jokers, 1967) might have been brought in to add a touch of levity to what otherwise – kidnap, rape – was a dodgy subject based on an original by Donald and David Cammell. Even taking a comedy approach wasn’t going to work if it was saddled with little interaction between characters and nobody, to put it bluntly, who could act.

I would tend to think with the “talent” involved that this was made by a neophyte producer. But, in fact, this is the oddest part of the whole debacle. John Bryson was an Oscar-winner – admittedly for art direction for Great Expectations (1948) – but also an experienced producer, this being the last of the dozen he made. But they included Man with a Million (1954) and The Purple Plain (1954), both toplining Gregory Peck, The Spanish Gardener (1956) with Dirk Bogarde, The Horse’s Mouth (1958) starring Alec Guinness, Tamahine (1963) – reviewed in this Blog – and Peter Sellers in After the Fox (1966).

It didn’t do anything for anyone’s career, which was the least you could expect for the actors forced into such mindless cavorting. Judy Huxtable appeared in a similar lightweight advertising-led concoction Les Bicyclettes de Belsize (1968) and bit parts in the likes of Die Screaming, Marianne (1971) and Up the Chastity Belt (1972). Ester Anderson did somewhat better, female lead to Sidney Poitier in A Warm December (1973), her last movie. For Kathy Simmonds this was her first and last movie, but she was better known as a genuine pop star’s girlfriend, dating George Harrison, Rod Stewart and Harry Nilsson. Only movie of David Anthony. Seems it’s too easy to confuse Marilyn Rickard with German Monica Ringwald so she may or may not have a string of bit parts in sexploitationers. Arts presenter Joan Bakewell put in an appearance as did Michael Chow, later a famous restaurateur and artist, and wrestler Ricki Starr.

Director Roger Freeman made one more picture, Secret World (1969) with Jacqueline Bisset which at least had a decent premise.

File under awful.