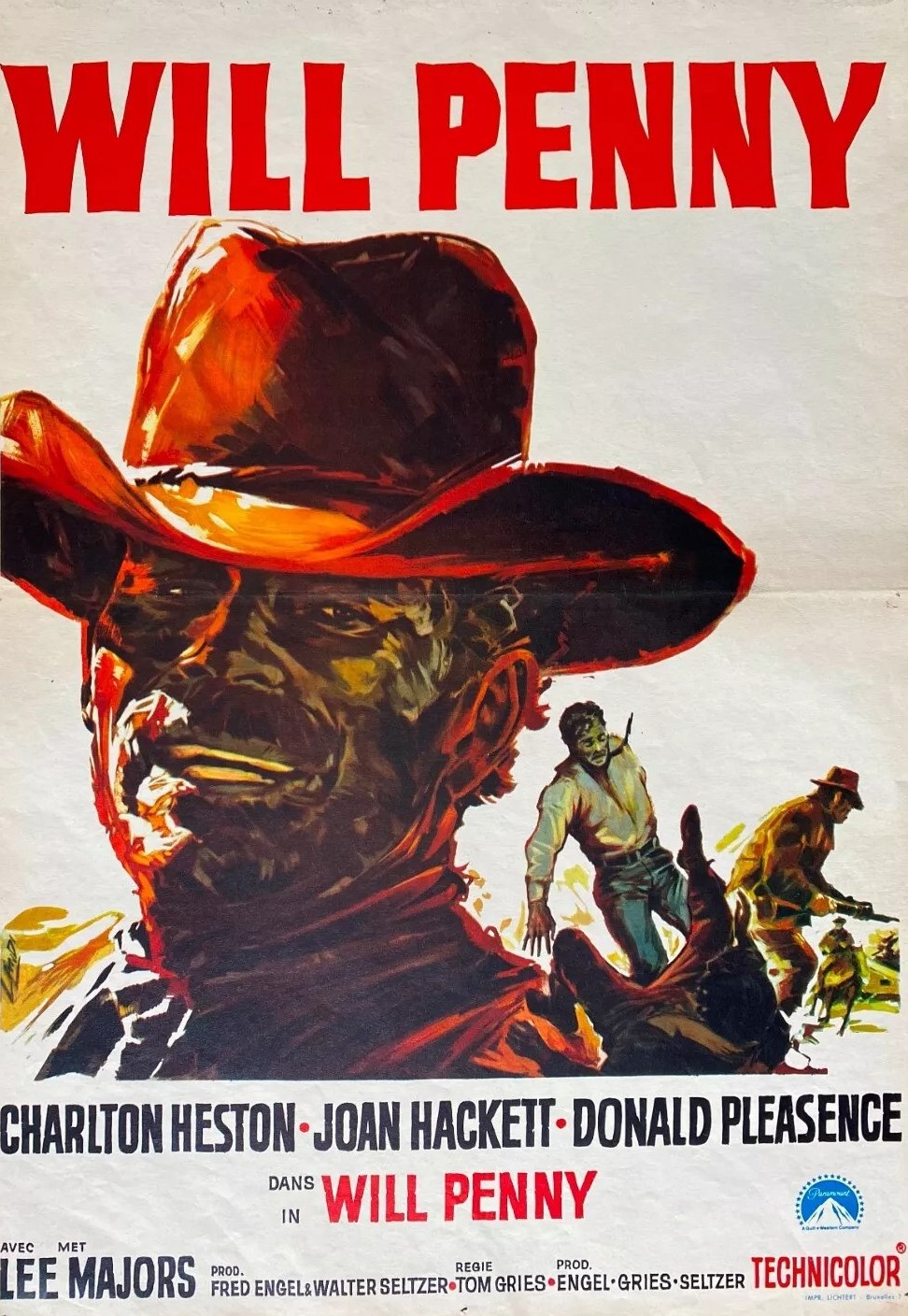

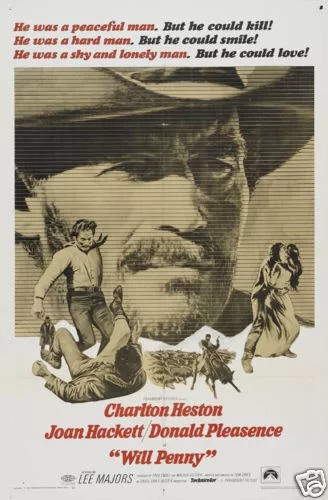

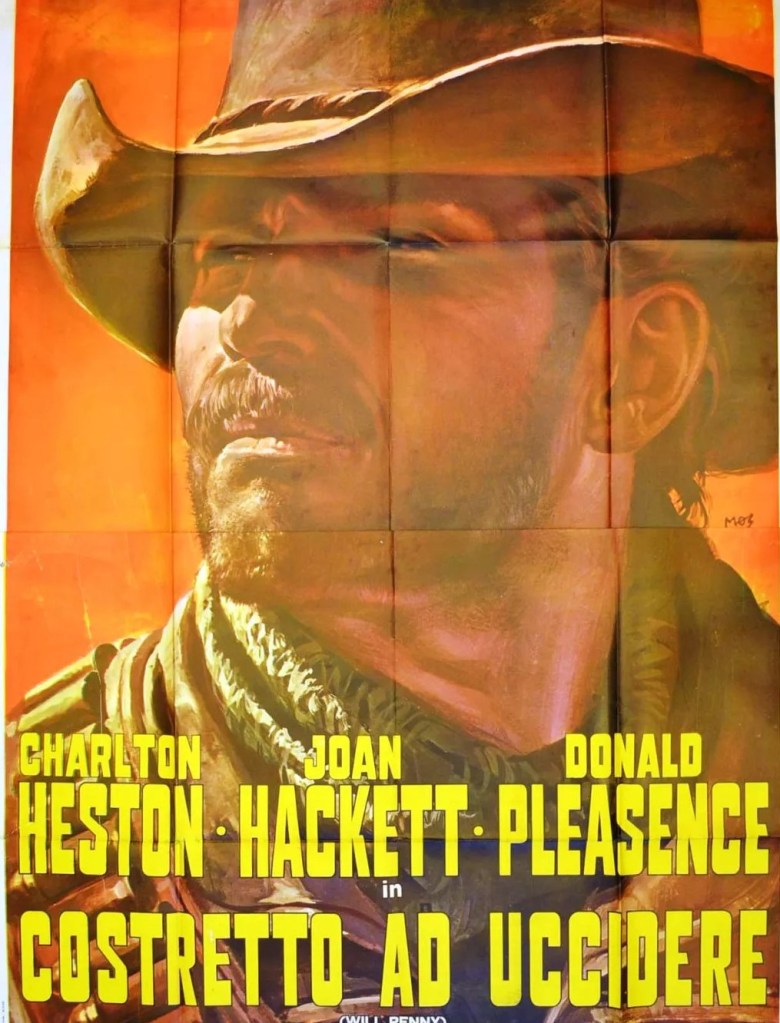

Tom Gries was a jobbing television director who had written a script he wouldn’t sell except with the proviso that he also direct. Sylvester Stallone with Rocky (1976) and Matt Damon and Ben Affleck with Good Will Hunting (1997) used the same ploy to ensure they were given the starring roles. In August 1966, the script reached Charlton Heston. “I read the first forty pages of a damn good western,” he noted in his diary, “if the rest is up to the beginning it could really be something.”

He had envisioned a director of the caliber of John Huston or William Wyler coming on board until his longtime producer Walter Selzer pointed out “the catch”. Gries was attached. Heston was on the point of declining but swiftly changed his mind. “The script’s so good, there’s really nothing else to do but give him a go at it.” The script became Will Penny, although Heston’s first reaction to the title was “that won’t do.”

This wasn’t Tom Gries’ movie debut though it was certainly a step up from the quartet of B-pictures he had directed in the previous decade – Serpent Island (1954) with Sonny Tufts, Hell’s Horizon (1955) starring John Ireland, The Girl in the Woods (1958) headlined by Forrest Tucker and Mustang! (1959) featuring Jack Buetel. But television was his beat, he’d even won an Emmy in 1964 for an episode of East Side/West Side with George C. Scott as a social worker.

Will Penny was based on his script for a 1960 episode of The Westerner called Line Camp. In preparing to write the movie, Gries spent two years researching “language, customs, fighting techniques and other aspects of the period” to provide the movie with an authentic feel. When it came to direction, he ensured the cowboys used antique weaponry rather than stock rifles and guns.

First call for funding was United Artists. The board turned it down “three to two.” Heston was “shocked” that the studio didn’t “recognize the value of this.” At that point, Heston was also putting together what became Counterpoint (1967), was in initial talks for Planet of the Apes (1968) and was also trying to get Pro/Number One (1969) off the ground.

Twentieth Century Fox was next to give Will Penny the thumbs-down. It was the same story all round Hollywood until Lew Wasserman of Universal showed an interest. But then rejected it. Finally, Selzer made a deal with Paramount, his first movie there since The Pigeon That Took Rome (1962).

Finding an actress willing to play the lead proved troublesome. Top of the agenda was Lee Remick (The Hallelujah Trail, 1965). Heston had two reservations. He considered her “too contemporary” and didn’t think “she’d be much help at the box office.” (She hadn’t had a hit since Days of Wine and Roses in 1962). She was the studio’s choice and although Heston’s contract allowed him to veto her casting, he couldn’t bring himself to do it. In the end, he didn’t have to take any action at all. After “all the fuss,” Lee Remick turned the part down. (Following The Hallelujah Trail she didn’t work again for three years.)

Next choice was Jean Simmons (Rough Night at Jericho, 1967), not as plain as the woman called for in the script, but a “helluva good actress.” Paramount chief Robert Evans was less keen. In the event Simmons was unavailable, so they turned to Eva Marie Saint (Grand Prix, 1966), “closer physically to our frontier woman.” But she rejected the script, too. They settled in the end on the less experienced Joan Hackett (The Group, 1966).

Meanwhile, Heston was trying to get into character, beginning with his clothing. “The look is the beginning, then you dig for the center.”

Filming started on February 8, 1967, on location in Bishop, California, shooting for around a month in the high altitudes. Heston was accommodated in a “not-quite-large-enough apartment.” It was slow going, Gries quite a one for the close-up especially in the action sequences. Some shots such as Heston milking a cow were edited from the final version. When the snow melted, bare patches of land were covered with detergent foam, “satisfactory enough in close angles, but we can’t cover enough for a long shot (and)…too slippery to work in for fight scenes.” A further fall of snow arrived five days later, the location covered in six inches of snow, ensuring that the previous week’s work required reshooting. But the “lovely snow” melting away every day created a deadline, calling for careful selection of which scenes to shoot on location and which to leave for the studio, consequently managing to finish location work only marginally over schedule.

To get the reaction he required from Heston and Lee Majors to drinking rotgut whisky, Gries plied them with straight gin. “If Wyler (famous for many takes) had been shooting it, we’d have been unconscious by the time he got a print,” noted Heston. This was an example of Gries’ inexperience. A good drunk scene was better played sober.

After two decades in the business, Heston had a technique that worked. “Since what you’re aiming for in a performance is the illusion of the first time, I like to start on takes as early as possible. I don’t forget lines, so I can nail down the necessary physical matches, then try to reach some truth in playing the scene.”

He was enough of an old hand, too, to ascertain when a scene wouldn’t work. “The scene (when the Quints captured the pair in the cabin) with Joan wasn’t really valid as written,” he pointed out. “To talk intimately within earshot of the Quints was unreal. We finally arrived at a concept of the scene where the Quints allow her to talk to Will so they can overhear and bait them.”

Sometimes, though, with an inexperienced director it was only failure that convinced. For the scene where Will pours sulfur down the chimney (to smoke the Quints out of the cabin), “I told Tom (Gries) we should begin with the acting scene and do the pickup shots with the sulfur later on, but he wouldn’t listen. I was right.” However, he conceded, “I saw Tom’s point. He wanted to shoot in sequence.”

On viewing the initial cut, Heston confided to his diary, “We may have something very worthwhile on our hands.”

Heston complained that Paramount, favoring movies instigated by the new management, “more or less buried the film.” But that wasn’t true. In the first place, this was made under the aegis of the new production team headed by Robert Evans. More importantly, Paramount made a determined effort to sell it as a serious picture, initial ads promoting positive critical response, leading with the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner claim that it was “quite possibly a classic.” However, its release was flawed. It was launched in Britain first, pitched out, again despite excellent reviews (“Gries…deserves an Oscar” proclaimed the London Evening News), in general release in January 1968 after a short run the West End. It may have suffered from the choice of premiere venue. Except for this one year, the Cambridge in cambridge Circus had operated as a venue for stage shows. It had been co-opted into becoming a cinema because so many other cinemas were tied up showing roadshows.

In the US, it was sent out in “selected engagements” in March 1968 but without hitting the box office target so that by the time it reached New York Paramount had ditched the “artiest campaign of the year” and reverted to more action-oriented marketing, dispensing with a Broadway first run in favour of a showcase (wide release) outing which generated an “okay” $189,000 from 31 theaters in its first week and $144,000 from 28 in its second.

Overall tally came to $1.8 million in rentals, placing it 44th in the annual chart, far below the sixth place and $15 million in rentals accrued by Planet of the Apes (1968) which didn’t appear till later in the year. Had release dates been swapped, and Will Penny sold off the back of the success of the sci-fi epic, it might have done better. In general, it was hampered by the downbeat ending and the overacting of the villains. Although initially touted for Oscar glory, all the movie won was the annual Wrangler Award, for best western of the year handed out by the National Cowboy Hall of Fame.

Despite not making quite the anticipated impact, nonetheless it set Gries up as a movie director. His next project, for Columbia, Fugitive Pigeon, based on a Donald Westlake novel, didn’t reach the screen.

Despite tabbing Gries “gifted, mercurial, oddly unpredictable and somewhat childlike”, Heston lined him up to direct Number One/Pro (1969) and The Hawaiians (1970). In fairness, Heston conceded that “given the right material, Gries was excellent.” Gries directed two more westerns, 100 Rifles (1969) and Breakheart Pass (1975).

SOURCES: Charlton Heston, The Actor’s Life, Journals 1956-1976 (Penguin, 1980); “Heston To Star,” Box Office, October 17, 1966, pW1; Advert, Kine Weekly, January 6, 1968, p2; Advert, Variety, March 6, 1968, p20; Advert, Box Office, March 18, 1968, p8; “Big Rental Films of 1968,” Variety, January 8, 1969, p15; “Rex Reed Case Histories,” Variety, February 19, 1969, p22; “Will Penny Winner of Wrangler Award,” Box Office, April 21, 1969, pSW2.