Arthouse noir? Cross between an Ingmar Bergman movie, except that the protagonist acts on her repression, and a Claude Chabrol with a character harboring festering desire. Certainly a bold choice for star Jeanne Moreau, excepting Brigitte Bardot France’s biggest female star, to play someone so malignant with scarcely a redeeming feature. Bold, too, in the setting, not the picturesque French village peppered with bright boulangeries and patisseries and with restaurant gatherings knocking back the wine. This is the reality of country life, ruled by religion and officialdom, little sign of ooh-la-la, and distinctly xenophobic – the minute anything goes wrong, blame the foreigner, in this case an itinerant Italian woodcutter.

It’s a distinctly arthouse notion to let the audience know straight off who the villain is while the villagers themselves are left in the dark about who caused two recent fires, their suspicions landing on Manou (Ettori Manni), the forester who arrives once a year so not quite an unknown entity, and too keen on seducing the local women.

We don’t know who the arsonist is, yet, either, but we might get a good idea from the opening sequence where some annual religious pageant, involving blessing fish caught in the river, is disrupted after a woman in high heels and black lace gloves opens a dyke, allowing a torrent of water to flood a farmyard, nearly drowning the animals, only the priest and a few boys left to continue the parade once the adults have raced back to the farm to save the livestock.

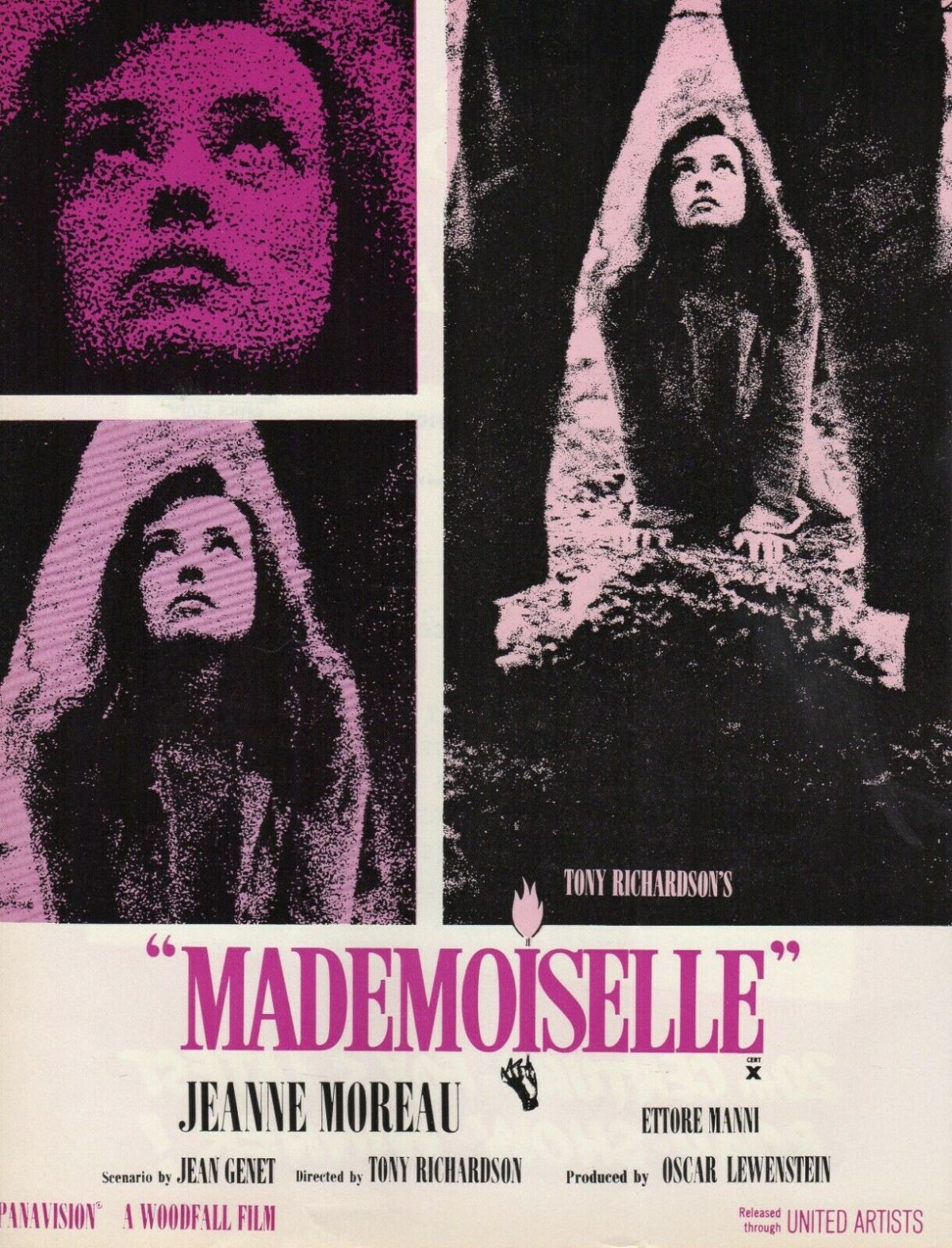

The woman is careful to wipe her high heels clear of grass as she places them in a wardrobe on a high shelf that contains other high-heeled shoes. We soon learn she is not just the schoolteacher but also volunteers her typing skills to the police, therefore keeping fully abreast of any investigation, and that she is held in such high esteem in the village that she goes by the name of Mademoiselle (Jeanne Moreau). While she defends Manou against accusations thrown around by the police, she victimises Manou’s son Bruno (Keith Skinner), ridiculing his clothing, making him stand in the corner or against a tree in the playground.

Turns out she’s the fire-raiser and in a small farming village there’s no shortage of houses with adjacent barns stacked full of straw that it only takes a match and a spill of flaming paper to set aflame. Foreigner Manou doesn’t act like an outsider, but dives in to help, at one point needing to leap to safety himself from a burning building. He doesn’t give his son much leeway either, ridiculing him and belting him across the face.

Only the camera catches Mademoiselle’s brooding intensity, the villagers intent on seeing only the upstanding part of her nature, judging her by the job that in an impoverished ill-educated area elevates her to a position of some standing in local society. Nobody dares come a-wooing. Maybe there’s a local squire somewhere around who might fit the bill. And certainly, she won’t lower herself like certain of the younger village females to make the first move.

As the fires grow more common, greater suspicion falls on Manou whom she secretly desires. Contrary to expectation, given the real power she wields in the classroom, and the secret power she wields over the community, her sexual hankerings run in the opposite direction. She wants to be debased, kissing the shoes of Manou when at last she makes her feelings known, howling like a dog, submitting to his domination which includes being spat upon and her clothes torn. You get the impression this might just be her playing out a fantasy except when she returns to the village with her clothes ripped and the women presume she has been raped she points the finger at Manou.

There’s no climax. We don’t see Manou being chased by a baying mob or being arrested as the film ends with her being driven away in a taxi, presumably to move onto the next village where she can continue her life of crime.

So, very much a character study. It’s hard to know when it’s set, but then raw village life hardly changes from one century to the next. Director Tony Richardson (The Loved One, 1965) makes no attempt to evoke sympathy for her. A few decades on when audiences took a liking to serial killers played by terrific actors (Silence of the Lambs, 1991, for example), moviegoers would have been more rapt by her exploits, almost willing her on, but this decade followed a different morality, filmgoers expecting villains of either gender to be punished.

Those sullen sulky features that Moreau previously used as part of her undeniable sexuality now seem turned-in, as defining of incipient evil as deformity was back in the early days of Hollywood.

Sensational performance by Jeanne Moreau (Viva Maria!, 1965) and also by Ettore Manni (The Battle of the Villa Florita, 1965) who proves far more sadistic than your run-of-the-mill seducer with attitudes to women that wouldn’t be out of place in the later giallo genre.

You might feel short-changed that there’s no resolution and that, in a sense, just like Bitter Harvest (1963), the director has skipped the third act and that there’s no real detection of her crimes, no cat-and-mouse between sleuth and villain. But it’s all the better for leaving out those elements. Written by Jean Genet (The Balcony, 1963).

Brooding and pitiless.

Thought I’d seen most of Richardson’s stuff, which is a bit hit or miss; this shound like one of the misses, but probably worth a look by your description; got Chabrol’s Le Boucher in my in tray…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Have to confess I didn’t think this would work and the reason why is down to the baleful Ms Moreau, adrift in her own vindictive island. Ditto Le Boucher.

LikeLiked by 1 person