Dry run for the director Richard Donner’s later Lethal Weapon? A cautionary tale about what might have happened to the revered Rat Pack series had it spluttered on into the vestiges of the “groovy” Sixties? An attempt to emulate the Bob Hope-Bing Crosby joker-crooner concoction? Or Morecambe and Wise, two idiots on the loose? Spy movie spoof? Stuffy Brits in the firing line?

All of the above. If you are comfortable with the sexist agenda that was almost de rigeur for the times, don’t mind the movie’s lurching tone, or the scattergun gag approach, the glib approach to violent death, and don’t cringe at the running racist jokes (making fun of racism, you understand) you might well find enough to like.

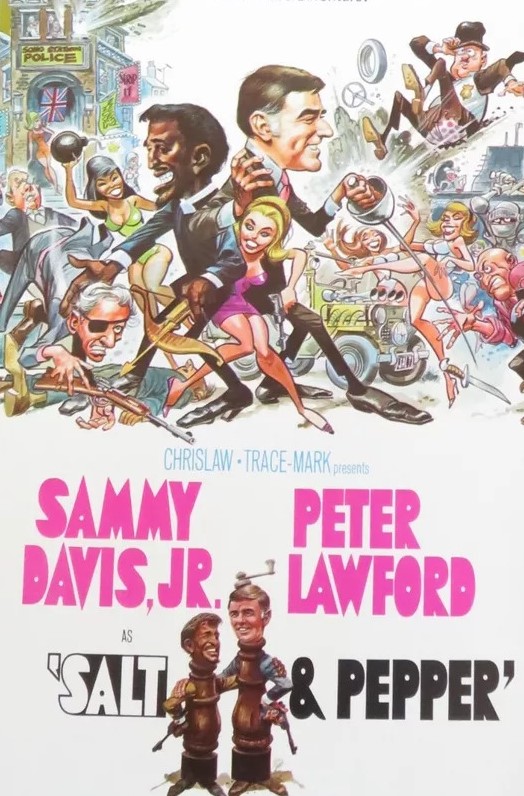

Especially as this was something or an audition. A way to check whether, in Hollywood marquee terms, stars Sammy Davis Jr. and Peter Lawford could cut it. For such a renowned celebrity, this was one of only two films where Sammy Davis Jr. was top-billed. And for Peter Lawford, an eternal supporting actor, this was the highest billing he ever achieved outside of the Italian-made The Fourth Wall (1969).

Salt (Sammy Davis Jr.) and Pepper (Peter Lawford) – that’s your first joke, right there, the names, work it out – are under investigation by the London cops for their Soho night club, which doubles as a gambling joint where the croupiers are not only, unusually, female (strike one for feminism) but topless (strike out for feminism). Both consider themselves lotharios and have a running bet on who will be the more successful (so that’s all right then).

But they’re not that bright when it comes to women (so one in the eye for those James Bond types), as neither could spot a femme fatale is she had those words branded on her forehead (the forehead the last female feature they’re interested in), and the prospect of an inert female lying on the office floor is so inviting to them that it doesn’t occur to them they’re trying to chat up a corpse.

Anyways, the dead woman Mai Ling (Jeanne Roland) is a spy and soon our boys are caught up in an espionage tale that dithers between hard-nosed Soho thugs with requisite scars (and a twitch), posh villain with piratical eye-patch, Downing St and duff British officialdom, real and fake Prime Ministers and Home Secretaries, public schools (and a gag about “fags”) and car chases in a Mini-Moke stacked with standard 007 extras like machine guns and oil-spraying devices.

So it’s one wildly imaginative situation after another, interrupted by stage turns by Sammy Davis Jr. (presumably to remind people this was a Rat Pack rip-off), with the cream of the British character acting fraternity being permitted to go way outside the stiff-upper-lip British box.

Fits neatly into the spy spoof, or the Eurospy spoof (which tended to be overloaded one way or another). Shame about the wayward direction and outlandish script because Sammy Davis Jr. and Peter Lawford do make a fine screen comedy pair, matching each other in ineptitude, and with Davis coming top of the Swinging Sixties Fashion Faux Pas Top Ten, with the kind of outfits that only attention-seeking nutjobs or villains would consider wearing.

Plenty of fun watching the supporting cast play around with their screen personas. John Le Mesurier (Midas Run, 1969), Michael Bates (Hammerhead, 1968), Robertson Hare (All Gas and Gaiters series, 1966-1971), Graham Stark (The Plank, 1967) and Ernest Clark (Arabesque, 1966) are getting paid to have fun. Ilona Rodgers (Snow Treasure, 1968) makes her movie debut.

You kind of get the idea that Michael Pertwee’s screenplay fell into the wrong hands. That it was intended as a vehicle for Morecambe and Wise (Pertwee wrote The Magnificent Two, 1967) and somehow ended up with American stars.

If your familiarity with the 1960s espionage genre runs only to James Bond, Matt Helm, Harry Palmer and that big-budget ilk and your idea of a spy spoof is limited to Casino Royale (1967), this will fill you in on the breadth of inanity tolerated.

Successful enough to generate a sequel, One More Time (1970).