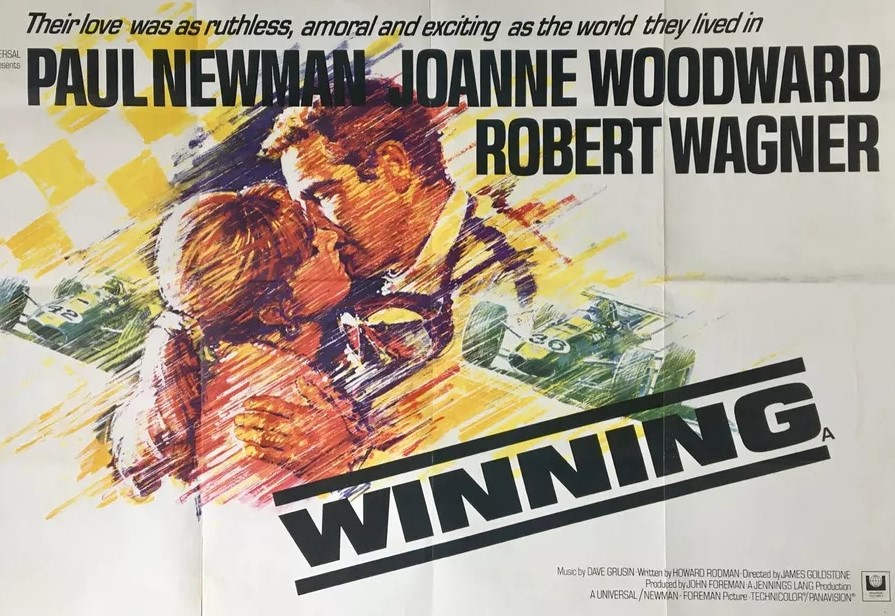

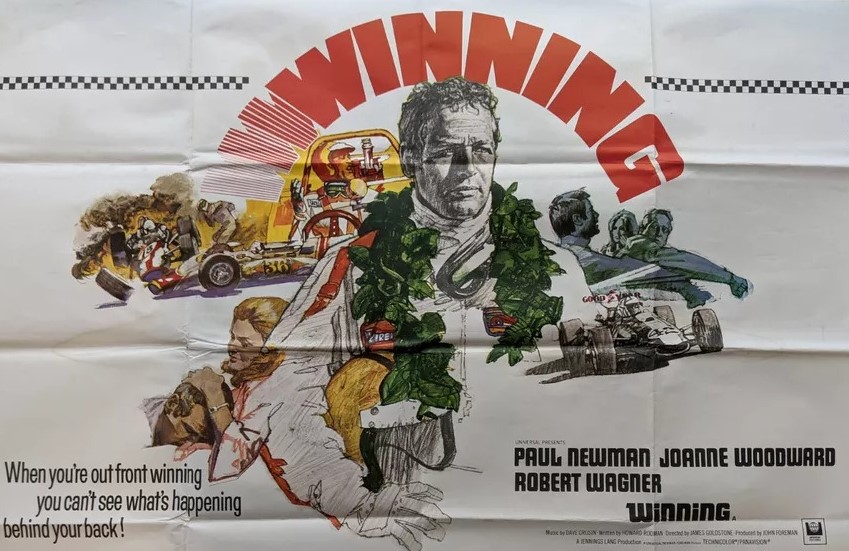

Boasting more marquee firepower than Grand Prix (1966) but less throttle on the track, faces the same problem as all racing pictures, namely, what to do with the cast when the camera’s not watching cars hurtle round and round. The John Frankenheimer Cinerama epic brought audiences much closer to the actuality of the circuit, though it fell down at the box office because U.S. moviegoers were less interested in Formula One than their home-grown variety, and filled up the off-track narrative with a clever concoction of politics, romance and revenge.

Le Mans ‘66/Ford vs Ferrari (2019) is the acknowledged ace of racing pictures, with terrific speed action, detailed engineering background, and the true-life tale of the manufacturing kingpin of America trying to wrest a crown from the European monarch, and with romance kept strictly off screen; I’ve no idea if Carroll Shelby had a wife or kids, that’s how disinterested this picture was in moving away from the central situation.

So what you inevitably have here is, to use the football idiom, a picture of two halves. And from today’s perspective, oddly enough it’s the off-screen maneuvers that take center stage. For the time, the racing sequences would have been interesting, not in the Grand Prix league, but then that didn’t make as much money as MGM would have liked, so it made sense to try and back up the spinning around with a more interesting story.

And this one’s a zinger, and the only reason the picture doesn’t work as well as it should is because the racing keeps on getting in the way of two hard-nosed individuals. There’s nothing particularly unusual about race ace Capua. He’s not of the win-at-all-costs league of Charlton Heston in Number One (1969), there’s no dodgy dealings for example, but he’s got the standard winner’s mindset, everything, including wife, takes second place to achieving his goal which in this instance is winning the Indy 500 (a 500-mile race round the same circular track about 200 times, not the twisting-and-turning racetracks of Grand Prix).

Even when he does win he lacks the champagne’n’sex personality of rival Erding (Robert Wagner) who’s usually got a girl on both arms and both knees and knows how to party. You’re more likely to find Capua wandering alone and drunk through the streets late at night with an empty hotel bed awaiting.

That’s where he meets single mum Elora (Joanne Woodward) shutting up shop (the hours they work!) in a car rental outlet (Avis, if you must know, since presumably they paid for the plug), the type of gal who looks a lot more straight-up than she turns out. She’s happy to dump her son on her mother and hightail off with new lover and he’s so smitten it’s not long before they’re married and she has to come to terms with the fact that he’s a lot more monosyllabic as a husband than a skirt-chasing Romeo.

What should have upset the applecart is her son, Charley (Richard Thomas), but Capua’s taken a shine to the teenager and spends a whole weekend – mum packed off elsewhere – getting to know him. Movies of this era didn’t waste any time on father-son bonding, kids mostly getting in the way of either romance or family life, and played for comedic effect (The Impossible Years, 1968, etc) or already having flown the nest and getting stoned. So this is pretty unusual territory and it’s well done.

But the real twist is Elora. Setting aside that she’s the kind of woman that dumps her son when a handsome hunk hoves into view, she looks like your typical mom, happy to sit on the sidelines and wait for hubby to come home and console him should he be on a losing streak. But Elora’s not that kind of woman at all. She needs attention. And if she doesn’t get it from a husband too wrapped up in his work she’s going to look elsewhere.

There’s an absolutely stunning scene that has little place in a sports picture when said handsome hunk, sporting god, top dog, finds her in bed with Erding. This has got to be Paul Newman’s best ever acting. And cleverly directed. The movie’s been toddling along with a nifty romantic score and that music’s playing as Capua heads home. But it shuts off suddenly when he opens the motel door. Tears brim in Capua’s eyes. The wife reacts from shame. No words are spoken. It’s all in looks.

Consequently, Charley takes against the erring mom and in a fast-forward to contemporary complicated maternal relationships she wants him to be her “friend.”

Of course, with her out of the way, Capua can get down to the serious business of winning, but that still leaves an emptiness inside. You’ll probably remember the famous freeze-frame ending of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), perhaps it’s no coincidence that Newman and producing partner John Foreman were in charge of that as well, because here they resort to the same technique. While, theoretically, this leaves audiences on an edge, it doesn’t at all, it just, as in the western, stops short of spelling things out. Elora’s much more self-aware than Capua, she’s making no moves to welcome a second chance, and you’re pretty darned sure this marriage ain’t going to get over her betrayal.

All the noise and razzamatazz of seeing the Indy 500 on the screen obscured the fine acting. Coming at it now with the racing sequences not appearing half as exciting as they must have been back in the day, and the twisty character of Elora to the fore, plus the exploration of the father-teenage son relationship, this has got a lot more to offer.

My guess is it gets marked down because the racing isn’t up to modern day expectations but ignore that and watch the acting. Joanne Woodward (A Big Hand for the Little Lady, 1966) steals the show, and, except in that one scene, beats Paul Newman (The Prize, 1963) hands down but that’s taking little away from the actor. In his debut Richard Thomas (Last Summer, 1970) shows definite promise, Robert Wagner (The Biggest Bundle of Them All, 1968) better than I’ve seen him. James Goldstone (When Time Ran Out, 1980) directed from a script by Howard Rodman (Coogan’s Bluff, 1968).

That bedroom scene takes some beating.

Time for a reappraisal.

I rememebr this as being a bit less than exciting, for the reasons you suggest; the racing scenes aren’t as exciting as I hoped. Might give this another look on your say-so, maybe the film might have matured or, less likely, maybe I have. Newman made some quite boring films between the iconic classics…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Story is interesting and good acting lift it up.

LikeLike

Filmed during the events of the 1968 Indianapolis 500 (though the start-line crash is from the 1966 race) which is why Paul Newman’s winning car was painted to match that of 1968 winner Bobby Unser (who has a cameo congratulating Newman on his victory). The film offers a great look at the old garages of Gasoline Alley that were torn down after the 1985 race and other elements of the Speedway that have changed dramatically since then. It’s also a reminder of how there was once a time when the Indianapolis 500 was THE undisputed great American race of them all, but sadly it and the Indy car circuit have lost their magic and luster over the last thirty years.

Newman’s love of the sport would lead him to a racing career of his own in the Can-Am series and in the mid-1980s he co-founded the Indy Car race team of Newman-Haas racing that remained a fixture in the sport for the next two decades (chiefly with Mario Andretti) though Newman would never get to experience victory at Indy as a car owner.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Indy does seem to have drifted away. Thanks for the background information.

LikeLike