“Producers must become real businessmen,” said Al Zimbalist, “and settle down to cutting corners.” [1] And he set about giving an object lesson in the art of cutting corners in producing Valley of the Dragons.[2] First of all the source novel by Jules Verne, Hector Servadac or The Career of a Comet, was out of copyright, in the public domain, so nothing was spent on that. Secondly, it just so happened that Columbia had a “magnificent” jungle set standing by, built at the cost of half a million bucks for The Devil at 4 O’Clock (1961), but now, that Spencer Tracy-Frank Sinatra effort complete, standing empty and to a producer with a persuasive tongue available at no cost.[3]

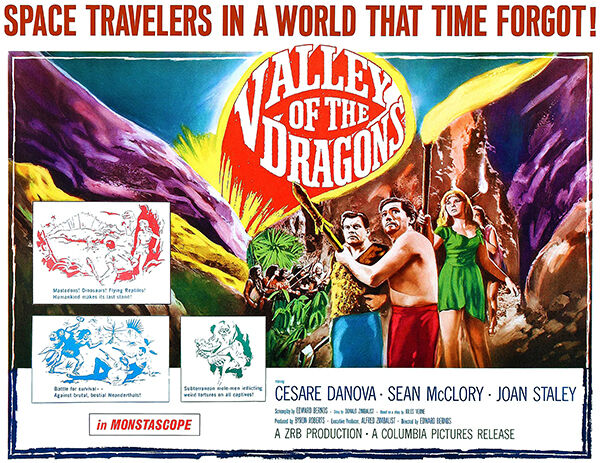

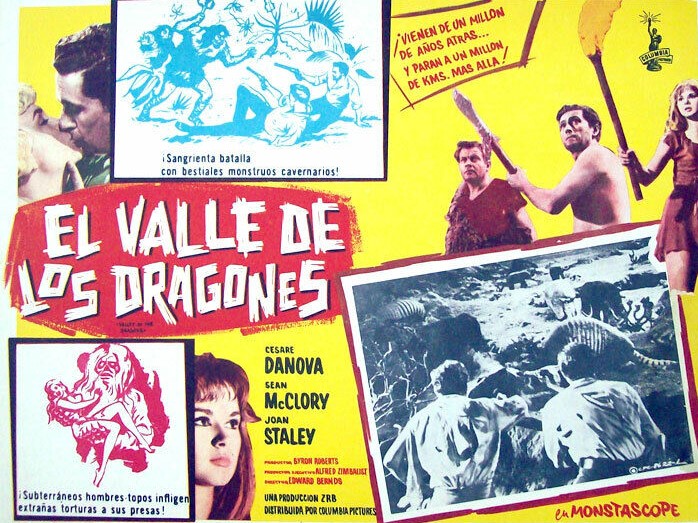

Thirdly, such a persuasive producer could convince Columbia to put a ceiling on the overhead they attached to any picture to cover their general office costs. Fourthly, he had acquired the rights to One Million B.C. (1940) and could plunder that picture for stock shots of prehistoric monsters. And fifthly, with budget limited in any case to $125,000,[4] he couldn’t afford to pay anybody much anyway and so was inclined to offer no more than $6,000 for the script.

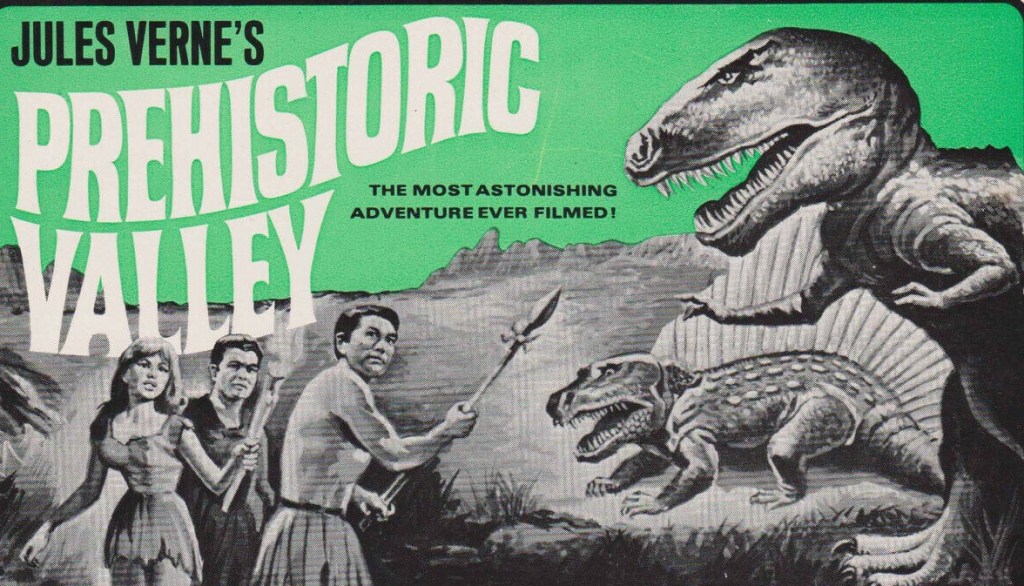

As it happened, Zimbalist could possibly afford to spend more given he was sitting on a $3 million worldwide haul from Baby Face Nelson (1957).[5] With partner Byron Roberts, he had just inked a multi-picture deal with Columbia, Valley of the Dragons the first product. Also on his slate: The Well of Loneliness based on the controversial novel by Radclyffe Hall, The Willie Sutton Story to star Tony Randall, a biopic of Bugsy Siegel and four television projects.[6] Zimbalist didn’t hang about. Valley of the Dragons went in front of the cameras on January 30, 1961, and was scheduled to hit U.S. cinemas in May[7] though ultimately it was delayed till the fall. Unfortunately, there was a surfeit of “dragon” pictures on the market what with Goliath and the Dragon and The Sword and the Dragon.

Zimbalist specialized in B-movies like Cat-Women of the Moon (1953), King Dinosaur (1955) and Tarzan the Ape Man (1959) in which Cesare Danova was second-billed. Baby Face Nelson, helmed by Don Siegel, was his best-made and most successful picture. Director Edward Bernds was cut from the same B-picture cloth with titles like Space Master X-7 (1958), Queen of Outer Space (1958) with Zsa Zsa Gabor and Return of the Fly (1959).

“Science takes a beating,” commented the director of the movie’s premise, explaining that it was not only unscientific but “utterly ridiculous.” The book, he claimed, had never been published in the U.S. because it was “viciously anti-Semitic” and it was brought to the producer’s attention by his son Donald, on vacation in London, who happened upon a second-hand copy in a bookstall. Although given a story credit – and thus some residuals – that was the only part Donald played in the making of the movie. The basic story was “shaped” by the stock footage. Bernds knocked out a 10-page treatment that Zimbalist shopped to Columbia. Although the budget was tiny, the producers would be due to pay for any overages.[8]

“The Jules Verne name meant box office at the time,” recalled Bernds.[9] Added Zimbalist, “Jules Verne was as big a name as Marlon Brando” with the advantage that “Verne never had a flop…with Verne you don’t need Marilyn Monroe.”[10] To help promote the movie, Zimbalist sent out on tour 50ft replica monsters and advertised it as being made in “Living Monstascope.”[11]

The special effects didn’t always go according to plan. While the giant spider’s jaws were spring-loaded and snapped shut thanks to magnets, the legs, operated by motors, did not always work and it was largely down to the actors to give the impression of an intense fight.[12] The rest of the special effects were simpler to achieve. An alligator given an extra dimension did duty as the dimetrodon, the T Rex was a giant blue iguana, a white nosed coati was passed off as the megistotherium, an Asian elephant covered in wool for the mastodon, while the pterodactyl came from the stock footage. “The cast was good, we had a reasonably fast cameraman…we didn’t have to spend a single day on location…and we did the impossible – brought the picture in on budget,” said Bernds.[13]

While the picture proved to be first run material, it didn’t top the bill, except in cinemas that gobbled up product, so initially it went out as support in 1961 to William Castle’s Mr Sardonicus (1961) but also played second fiddle to Mysterious Island, Weekend with Lulu and The Mask. [14] Results were mixed: a “fair “ $11,000 in Boston, “bright” $20,000 from five houses in Kansas City, “sluggish” $5,000 in Portland and “good” $13,000 in San Francisco.[15] It must have done well enough for it was revived the following year and topping a bill in Chicago that included Eegah (1962)[16] while an exhibitor in Texas deemed it a “nice surprise…will do good business for a Saturday playdate.[17]

Zimbalist didn’t realize his ambitions with Columbia. None of those projected movies materialized, nor did an anthology television series based around the works of Jules Verne.[18] He was quick off the mark to register the title Lucky Luciano after the gangster’s death in 1962,[19] but that didn’t translate into a movie. In 1964 he lined up a $2 million slate with Allied Artists including King Solomon’s Mines, Planet of the Damned, Jules Verne’s Sea Creature and Young Belle Starr.[20] But none of that quartet reached the screen either and his final pictures were Drums of Africa (1963) with MGM and the indie Young Dillinger (1965) which prompted an outcry over the violence.

Byron Roberts enjoyed a longer career, with credits for The Hard Ride (1971), Soul Hustler (1973) and The Gong Show Movie (1980). For good or bad, Bernds was rewarded for his efforts on Valley of the Dragons by becoming the go-to director for The Three Stooges, helming The Three Stooges Meet Hercules (1962) and The Three Stooges in Orbit (1962) before sidling off for the animated version of their antics.

[1] “Varied Guesses on IA’S New Wages & Small Pix,” Variety, February 8, 1961, p3.

[2] “Another Jules Verne Yarn To Be Made Into Pic,” Box Office, May 1, 1961, pW!.

[3] Tom Weaver, Interviews with B Science Fiction and Horror Movie Makers (McFarland), p62-64.

[4] Weaver, Interviews, p62-64

[5] “Varied Guesses.”

[6] “Zimbalist, Roberts Pact with Columbia Carried Video Angle,” Variety, January 18, 1961, p17.

[7] “Monsters in Droves,” Variety, February 15, 1961, p4.

[8] Weaver, Interviews, p62-64.

[9] Weaver, Interviews, p62-64.

[10] Murray Schumach, “Hollywood Mines Gold in Jules Verne,” New York Times, February 3, 1961.

[11] “Monsters in Droves.”

[12] Weaver, Interviews, p51-52.

[13] Weaver, Interviews, p62-64.

[14] “Back St Holds Pace in 2nd Detroit Week,” Box Office, November 20, 1961, pME4; “Hawaii and Commancheros Neck-and-Neck in Seattle,” Box Office, December 4, 1961, pW3; “Hawaii Is Hartford Favorite a 2nd Timer,” Box Office, December 11, 1961, pNE1; “Mysterious Island Tops,” Box Office, January 8, 1962, pSE8.

[15] “Picture Grosses,” Variety: November 1, 1961, p8; November 8, 1961, p10; November 29, 1961, p15; December 6, 1961, p9.

[16] “Picture Grosses,” Variety, June 6, 1962, p9.

[17] “The Exhibitor Has His Say,” Box Office, July 2, 1962, pB6. This was at the Galena Theater.

[18] “Zimbalist-Roberts 3 Vidfilm Skeins,” Variety, April 5, 1961, p30.

[19] “Dead, Lucky Luciano Looks Sure for Filming,” Variety, January 31, 1962, p1.

[20] “Zimbalist Finances, 12 Go Allied Artists,” Variety, June 10, 1964, p4.