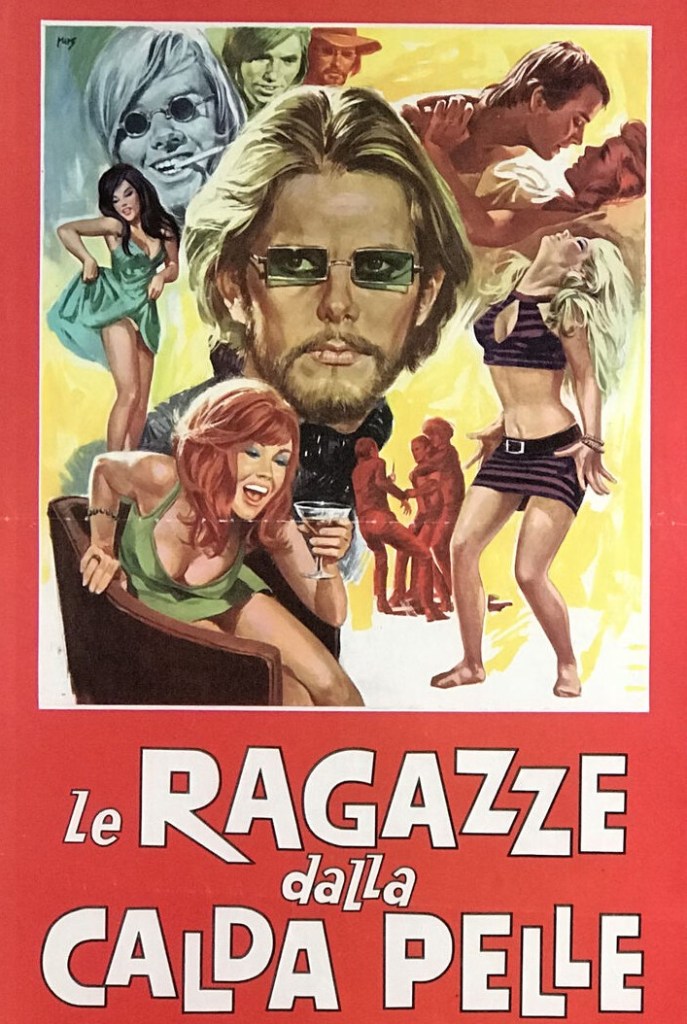

Catholic high school girls in trouble? Call Sam Katzman. Delinquents, crazed by music or booze or sex or drugs (maybe all four), on the rampage? Call Sam Katzman. Thugs, to quote from Johnny Cash, keen to “watch a man die?” Call Sam Katzman. The new generation threatening to swamp the old? Call Sam Katzman. Require a sensuous lass in tight clothes to perform an Ann-Margret-style number? Call Sam Katzman.

Legendary five-and-dime producer Sam Katzman, with over 200 pictures in his portfolio, had put his stamp on everything from the East Side Kids and jungle flicks to horror, westerns and sci-fi. Any new genre with rip-off potential, he’d be first in the queue. Forget knives and guns and fists, music was the most dangerous weapon, over-exciting the young.

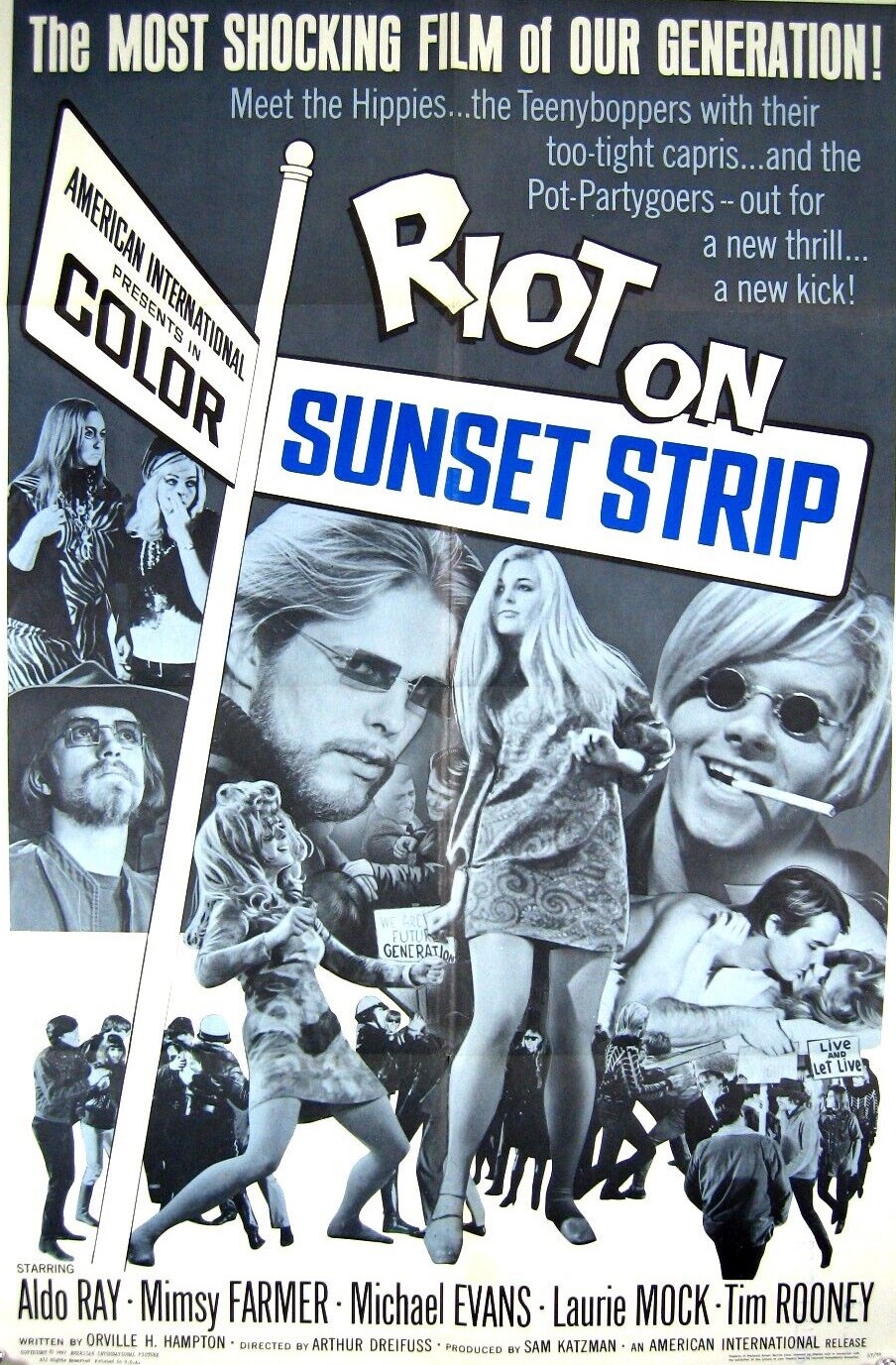

So no surprise then to find the man behind Rock Around the Clock (1955) and Calypso Heat Wave (1957) also responsible for Teenage Crime Wave (1955), New Orleans Uncensored (1955) and Hot Rods to Hell (1967). Or that he’s an exponent of the old bait-and-switch here – no riot here that I could spot.

And probably over-emphasis on earnestness for a potential exploitationer, from the occasional intrusions of a pseudo-documentary voice-over to the grown-ups debating the causes of the latest outbreak of teenage rebellion, long hair, marijuana, popping pills and energetic dancing. That said, it’s even-handed, adults blamed for the divorce plague that leaves youngsters alone and vulnerable, cops too prone to violence, greedy businessmen and characters with right-wing tendencies causing the problem or making matters worse. “They’re just kids,” spouts earnest top cop Lorrimer (Aldo Ray), “they could be your sons and daughters,” not realizing one of them is.

Away from the grown-up talk-fest, the kids sit either numb listening to loud rock bands in far from sleazy clubs or on the dance floor pounding away to the beat, in either case not having much to say to each other, and inevitably ending up out the back door smoking a quiet joint or gathering in some pretty fancy home for a tripping party

Andrea (Mimsy Farmer), a youngster from a broken home living with her drunken mother, falls in with a bunch of teenagers who hang out in these hard-wired locales. Initially, she resists joining in, and perfectly innocent when caught up in a scuffle. But when supposed cool dude Herbie (Schuyler Hayden) spikes her drink with some acid at a party she turns all Ann-Margret, and is allocated a near six-minute slot to shake her stoned booty, leading the aforesaid Herbie to take her upstairs and take advantage. Doesn’t end well for Herbie as she’s under-age.

Turns out, too, Andrea is not so much the long-lost as abandoned daughter of Lorrimer and when he goes into rescue mode she gives him both barrels. “You left me alone for four years, let’s keep it that way,” she snaps. Apprised of her situation, he sets about the youngsters with his fists.

That supposedly leads to the riot. But it’s no more than the mildest of protests as he has to endure a Walk of Shame a la Game of Thrones (though with clothes on) and, bizarrely, becomes the poster boy for both police brutality and for anti-police-brutality. Natch, there’s a tacked-on happy ending but not before the voice-over can intone in apocalyptic manner: “Half the world’s population is under 25. Where will they go? What will they do?”

I had come at this because I was intrigued to discover Mimsy Farmer as the junior minx in Spencer’s Mountain (1963) and as she was overshadowed by Ann-Margret in Bus Riley’s Back in Town (1965) wondered how her career had progressed. Presumably come to a standstill, otherwise she wouldn’t have ended up in a B-picture cul de sac. She puts in a good performance, however, miles away from the lively youngster of the Henry Fonda picture, withdrawn, anxious, not fitting in.

A good chunk of the picture is wasted, from today’s perspective, on no-name bands and not much happening, but the talk-fest aspects prove that little has changed in the way the grown-ups misunderstand the young and much the same arguments for reining in the supposedly out-of-control teenagers are still being trotted out today. But it does point a prescient finger at marriage break-up (the fault of the grown-ups doing much of the blaming) as a root cause of teenage misbehavior and contemporary audiences will only be too familiar with predatory males spiking drinks.

Aldo Ray (Welcome to Hard Times, 1967) would be the marquee name, but you try and compete with a lithe teenager who says more in her six minutes of pent-up emotion and the resultant dancing than all the time spent on earnest debate. Laurie Mock (Hot Rods to Hell, 1967) is the wildest of the females.

Director Arthur Dreifuss was a Katzman regular but was also responsible for the movie version of Brendan Behan’s The Quare Fellow (1962). Screenwriter Orville H. Hampton had a surprising pedigree with Cage of Evil (1960) and Jack the Giant Killer (1962) and Oscar-nominated for One Potato, Two Potato (1964).

More absorbing than I expected and Mimsy Farmer’s trip a lot more interesting than Peter Fonda’s.