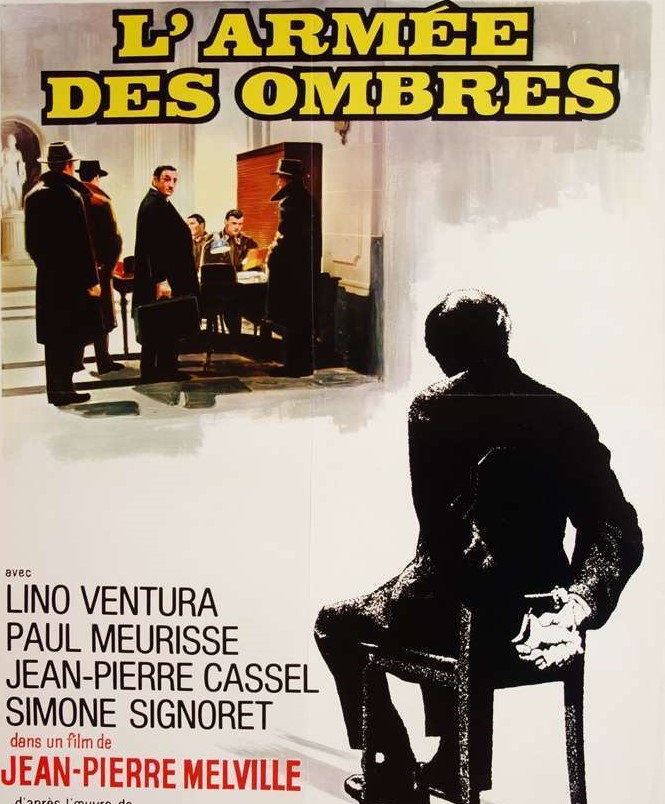

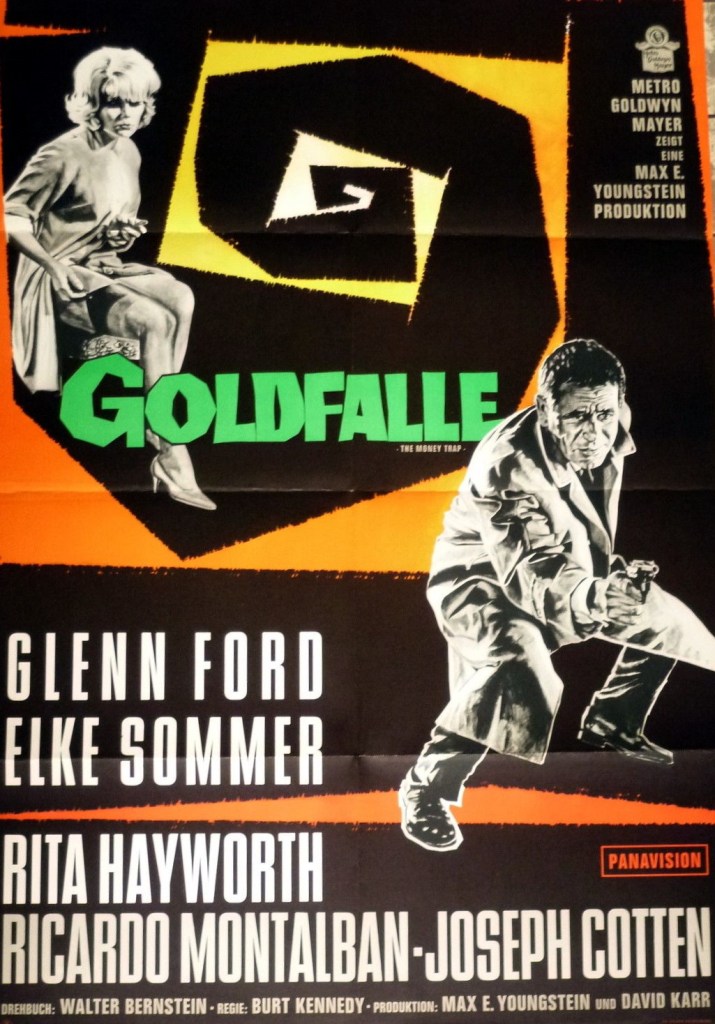

Film noir morality play. Highly under-rated, especially unfair since all four principals put in excellent performances, plus a nifty screenplay, and generally erratic director Burt Kennedy on very solid cinematic ground, even if he has a predilection for showing legs, and not just of the female variety.

Film noir is at its best when the plot is simple, usually good guy inveigled into taking a wrong turn through avarice, revenge or a femme fatale. This takes an unusual route. Idealistic cop Joe (Glenn Ford) worries beautiful wealthy spendthrift wife Lisa (Elke Sommer) will abandon him for a richer guy since her allowance has dried up.

Assuming she is already making her play, Joe has a one-night stand with old flame Rosalie (Rita Hayworth), a lush married to a murdered burglar. His partner Pete (Ricardo Montalban), envious of his buddy’s wealth, blackmails him into robbing the safe of Mafia doctor Van Tilden (Joseph Cotten) who, in self-defence, killed the burglar. Meanwhile, as contrast, the pair are investigating the murder of a sex worker trying to earn extra money to shore up her husband’s miserable income.

While it’s got all the requisite of film noir, atmospheric use of light given it’s shot in black-and-white, that unusual footage of legs, and feet, especially when Rosalie is followed by Tilden’s thug Matthews (Tom Reese), cunning villain, the unexpected twist, neither of the femmes it transpires is much of a fatale, greater backbone than you might expect.

But mostly, it focuses on decision and consequence. Will Joe accept he could lose his wife, will Lisa make the jump into a lower standard of living in order to hold onto her husband, or will Joe distrust that his wife can change and find a way to bring the loot he thinks will keep her satisfied? Lack of trust all round proves their undoing.

There’s the usual, silent, heist, though quite where Joe and Pete acquired their safecracking skills is never discussed. It is the perfect robbery, a dodgy doctor unlikely to call in the cops, especially as they might get suspicious as to just why he is such a common burglary target. Except it’s not. For what’s in the safe is too hot for any cop and Van Tilden, more streetwise than the police, is always one step ahead. Instead of it being the greedy Lisa who could ruin their otherwise stable and loving marriage, it’s Joe.

There are a handful of clever twists, not least that Joe’s dalliance with Rosalie signs her death warrant, but I won’t give those away. It’s too tightly told to spoil it. That’s part of the beauty here, it’s a neat 90 minutes, short and to the point, temptation and consequence.

If ever there was an actor under-rated during this decade it’s Glenn Ford (Rage, 1966). He was hardly ever cast in a big-budget picture except as part of an “all-star cast”, and mostly, given the extravagances elsewhere, in A-pictures whose budgets in reality turned them into B-pictures, and he ended the decade in a rut of westerns, all as under-rated as him. But he brought a tremendous intensity to every role, equally believable as romantic hero and potential heel, and in action, as here, he moves with lethal speed. He had a unusual gift as an actor – you always knew he was thinking. And was very likely to be saying one thing and thinking or meaning another.

Here he acts his socks off. You wonder just what has he got to live in such a fancy house with a rich gorgeous damsel and it doesn’t take long to find out his attraction to him, that right stuff that would rarely come an heiress’s way, more likely to trundle her way through endless marriages and affairs seeking a stability that wealth does not bring.

Elke Sommer (They Came To Rob Las Vegas, 1968) is a revelation, mostly because the script builds her a proper character, loving wife temporarily distracted by potential loss of wealth, but knowing enough about her husband to recognise she’s be better off with him than without him.

Rita Hayworth (The Happy Thieves, 1961) makes the most of her last meaningful role, not lit to shimmering glory by a black-and-white camera, but while shown at her blowsy physical worst redeemed by mental strength. Ricardo Montalban (Cheyenne Autumn, 1964) , usually relegated to a supporting role, provides not only the narrative impetus, but his character twists and turns throughout. Joseph Cotten (Petulia, 1968) has cold blood running through his veins.

This is early-promise Burt Kennedy (Dirty Dingus Magee, 1970) and with a tight script by Walter Bernstein (Fail Safe, 1964) delivers a surprisingly effective very late period film noir.

Terrific acting, by twisty plot held in check by realistic consequence.