Only spaghetti western directed by a woman. Brings a distinctly feminist feel to that most sexist of the subgenres. You tend to forget that the sexy female Europeans imported to Hollywood as co-stars or to add spice further down the credits were actually top-billed stars in their natïve countries and demonstrated a greater range than the American industry allowed.

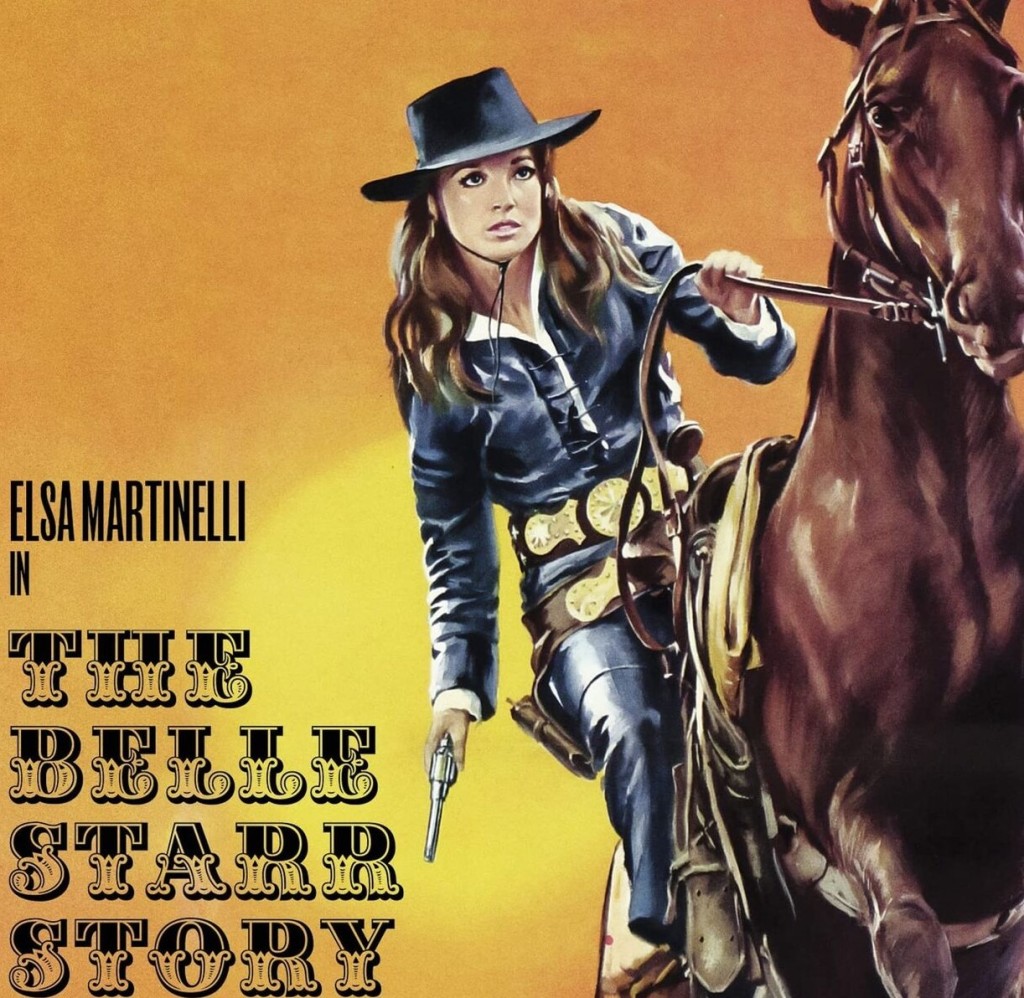

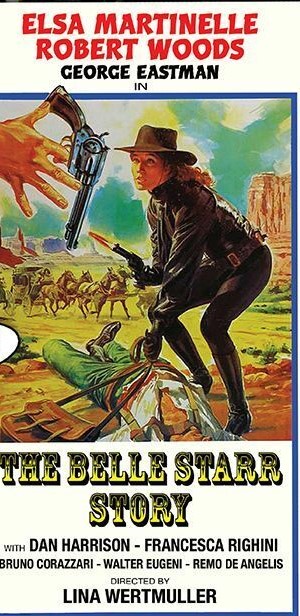

Not only do we have Elsa Martinelli (Maroc 7, 1967) as the leather-clad cigar-smoking titular gunslinger, whose watchword is female independence, but it was helmed by arthouse icon Lina Wertmuller (Swept Away, 1974). There’s a thematic consistency lacking in most Italian-made westerns, for example predating Once Upon a Time in the West (1969) in its water imagery. But any potential for lyricism is undercut by the risk attached to being a lone woman. And there’s a Tracy-Hepburn tone to the endless bickering and battle for superiority in her niggling romance with outlaw Blackie (George Eastman).

And, unusually in that decade, a woman who throws caution to the wind and will even bet her body when the money runs out at the poker table, as twisty a meet-cute as a screenwriter could devise. But thereafter it’s a struggle for dominance between the pair. She won’t take orders from a man. He won’t accept female equality even when she shoots the wooden fence he’s sitting on from under him, making him fall to the ground, and for good measure putting a bullet in his heels.

The first act builds up Belle Starr, cool at the poker table, even cooler in the bedroom, and demonstrating the gunplay that attracted her notoriety. The second act take an odd route, a lengthy flashback that digs deep into feminism, the orphaned Belle Starr running away after being sold into marriage by her uncle to an ugly old rich powerful man, traded, effectively, for political favor.

She returns to save a servant condemned to death for the crime of attacking the uncle when he tried to rape her. Sexual humiliation is a theme. Another outlaw Harvey (Robert Woods), who she regards as a platonic friend, steals her clothes as she swims in a lake, and then, having saved her from a posse, forcibly tries to take his reward.

The third act, like the duel between The Man With No Name and The Man in Black, is a case of double- and triple-cross. She refuses to join Blackie’s gang when he plans a million-dollar jewel heist, but hijacks the concept, recruiting her own gang to beat him to the robbery, and teach him a lesson.

But it backfires. Blackie is waiting. She has inadvertently hired his men. In the subsequence shoot-out he is captured. She rides to his rescue. But with their opposing ideas of a woman’s place in the world part on good terms.

The flashback was more subtly observed in Once Upon a Time in the West, and while she shared with Charles Bronson gunslinging skills he was not at any time viewed as a commodity or a piece of property or a candidate for rape. The flashback here fleshes out for the audience the powerlessness of women. But also the kind of camaraderie that is generally also usually only conferred on male characters.

We are pretty conversant with the notion that the gun rules the West. But less conscious of what happens when you are gun-less. Depriving someone of their fundamental weaponry makes them instantly impotent, as humiliating as denying someone water in a desert.

There are some nice directorial touches, blood dripping from a ceiling onto a dinner table, a saloon door opening to cast sudden light onto a corpse, waterfalls suggest sanctuary whereas open water attracts predatory males, and the finale, as they part, of Blackie, desperate to demonstrate his superiority, shooting off her hat from some distance.

Elsa Martinelli is a revelation as a star working to her own beat rather than playing second fiddle to some Hollywood marquee name. This wasn’t Lina Wertmuller’s first film and she had already made an impact with the Rita the Mosquito series, featuring another rebellious woman. Don’t be fooled by the co-directing credit, she replaced debut director Piero Cristofani after a few days.

It’s somewhat ironic that in a contemporary Hollywood attempt to create a female outlaw leader in Cat Ballou (1965), Jane Fonda was upstaged by Lee Marvin, and that in Bonnie and Clyde (1967), despite taking precedence in the title, Faye Dunaway was not the dominant one in the relationship.

By no means a great western but worth a look to see what Elsa Martinelli can achieve when not slotted in to the Hollywood co-star cliche and to get a preview of what Lina Wertmuller could offer.

Decent print on YouTube.

I might give this a go; you had me at ‘the leather-clad cigar-smoking titular gunslinger, whose watchword is female independence’

So is there any connection to this? Belle Star was a real person, and there were other films? 1941?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Gene Tierney made her name as the original heroine but minus leathers and cigar.

LikeLike