Still astonishing that the two movies that rocked sci-fi to its core came out the same year. Initially beloved mostly by dopeheads 2001: A Space Odyssey quickly achieved ultra-academic status. But it’s difficult to ignore the fact that that Planet of the Apes had the greater long-term effect, given it spawned umpteen sequels and two sets of remakes.

You could also argue that the concept is even bolder than the Kubrick, not just man’s treatment of animals, but the idea of man being subject to a superior species, and inside an action-packed picture there’s plenty of time to digest the unimaginable and engage in debate about the nature of man. The elevator pitch might have been: “Take Hollywood’s strongest hero and torture him one way or another.”

Part of the movie’s genius is the unsettling opening, swirling, almost deranged, camerawork, a discordant score, the confident occupants of a spacecraft heading into the unknown finding the kind of unknown that fills them with dread rather than awe. Two thousand years into the future a spaceship doesn’t gently touch-down on a strange planet, but crashes into it, luckily landing in a lake, the three survivors escaping the sinking craft.

The audience knows a great deal more than they do, that the arid desert in which they find themselves stretches everywhere. But then they realize, with supplies that will last only three days, the soil here will not support life. But they are quickly upbeat when they find a small plant followed by substantial greenery. The sight of crucified figures on a hill is put to one side when they hear running water and rush to dive naked into a pool, confidence restored that they won’t die of thirst and should at least be able to eat vegetable matter.

The pool is a clever reversal. Usually open water is there for a female to disport herself. Now we’re seeing Charlton Heston’s bare backside. And another reversal: when clothes disappear it’s usually so a female has to come out of the water exposed.

But from the sight of the crucified apes, for the next seven minutes, their world is completely turned upside down. Chasing after their clothes they find inhabitants, automatically assumed to be inferior because they are mute and dressed like cavemen. But then the tribe hears a noise and panics. We see horses hooves, the tops of the flailing sticks used to beat prey out from the undergrowth, rifles, the natives, like dumb beasts, being driven into nets.

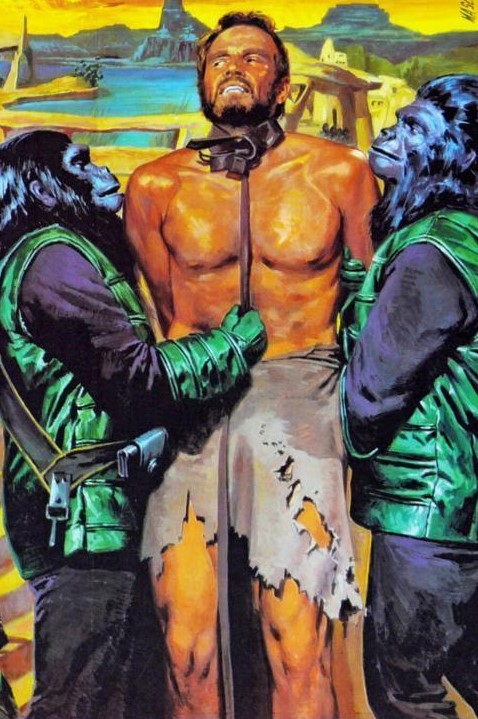

Then the first sight of an ape astride a horse wielding a gun. There can’t have been a more astonishing image, not even from the mind of Stanley Kubrick, in the whole of Hollywood sci-fi. Man is not just an alien in a world ruled by apes, but treated like an animal and only kept alive for scientific experiment. That man is rendered mute is hardly surprising because the apes don’t expect their captives capable of uttering an intelligent word.

From then on we’re in familiar and unfamiliar territory. There’s little more cliched than a captive trying to escape, success and failure the next beats. There’s little more cliched than a captive striking up a relationship with an imprisoned female, the pair contriving to achieve freedom.

Where this breaks new ground is that, in addition to making a connection with Nova (Linda Harrison), Taylor (Charlton Heston) woos a female ape scientist Zira (Kim Hunter) who tries to help him become accepted by her people. In the opening section, Taylor had opined, “somewhere in the universe there must be something better than man” but in the arrogance of humanity had assumed he be treated as an equal rather than an inferior.

So it becomes a duel of words. Taylor forced into being told how terrible humans are, and it’s hard to argue with the ape conclusion, while at the same time making the case for mankind, and especially himself, as a special type of species. There’s more than enough meat in the script, riddled with brilliant lines, to make audiences think deeply about the impact of man on the world. You could cast your mind back to the slaves of Spartacus (1961), trying to be accepted as equals, forced into revolt when that is denied. And to some extent that’s the imagined set-up here: Taylor will escape and establish some kind of resistance movement.

But that’s not what director Franklin J. Schaffner (The War Lord, 1965) has in mind at all. He’s been leading us by the nose to the most stunning ending in all of sci fi, and one of the most astonishing climaxes in the entire history of the movies, a shock wrung through with irony.

The movie is a supreme achievement, in springing its multitude of audience traps, turning the world upside down. Jarring soundtrack and discomfited camerawork add to the stunning images. The ape world is revealed as complex, filled with engaging characters.

Outside of Number One (1969), this is Charlton Heston’s best performance as he moves through a range of emotions, cocky, puzzled, confident, baffled, captive, pleading, arguing the case for humanity, before spilling out into straightforward heroic mode of escapee. For the first time ever Hollywood now had a genuine box office star to headline sci-fi pictures and Heston would carry the torch for The Omega Man (1971) and Soylent Green (1973)

At every level a masterpiece.

Great review of a genuinely iconic movie that still holds up magnificently. You are very much on the mark about it being much more a zeitgeist movie than “2001” at the time which makes its current status as little more than yet another over-milked IP at best (and tired “Simpsons” reference for dimwitted middle-aged fanboys at worst) so appalling.

Have you read the coffee table-sized making-of book that came out about five years ago? It’s a fascinating read and a perfect example of how the best way to adapt a book is to sometimes rethink it from the ground up.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I had the book but loaned it out and never got it back.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sorry, just read your message but as I commented in today’s post, “There’s a special place in hell…

Thanks for writing about this film. It really deserves a lot more love.

Get Outlook for Androidhttps://aka.ms/AAb9ysg ________________________________

LikeLiked by 2 people

A great film, obviously, but the latest trilogy did the core idea proud IMHO. I wish I could have seen this with an audience in 1968, I’m imagining Sixth Sense levels of shock at that ending. An easier film to digest than 2001, and while it’s apples and oranges, they’re both stone cold classics. Apes probably has more wit, and comparisons to the Boulle novel indicate what a radical re-think it got here…

LikeLiked by 1 person

The latest trilogy was more sympathetic to the apes but there’s nothing to beat the original and you will never top that ending.

LikeLike

Your review is so accurate about that great adptation. That was a real pleasure to revisit the film through your words. Pierre Boule wrote a masterpiece and Schaffner did its best to not betray the original book. That leads us to this tremendous final. The next version made by Burton is forgettable. After that, I skipped. So, for me, the Schaffner is the best of all.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Agreed. It’s a long time since I read the novel and I’m itching to see how much was changed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Found this:

“The film’s opening credits begin after a sequence in which Charlton Heston, as “George Taylor,” records his thoughts during the long space voyage and then puts himself into suspended animation, along with the rest of the crew. The ending credits include the following written acknowledgment: “The Producers express their appreciation to the National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior, for its cooperation in the production of this motion picture.” In 1964, news items reported that the screen rights to Pierre Boulle’s popular science fiction novel, La planète des singes (Planet of the Apes), had been purchased by Warner Bros., with the film to be directed by Blake Edwards and produced by Arthur P. Jacobs. Rod Serling completed the screenplay by Nov 1964, according to an 8 Nov 1964 NYT news item. On 10 Mar 1965, DV reported that due to “budgeting and production problems,” the project was being postponed, thereby excluding Edwards from the project, as Edwards was about to embark on a six-picture contract with The Mirisch Corp.

On 17 Oct 1966, HR and DV announced that the film would be a joint venture between Jacobs’ independent production company, Apjac Productions, and Twentieth Century-Fox. Although a 24 Oct 1966 HR news item announced that Charles Eastman had been signed to work on the screenplay, he is not mentioned by other contemporary or modern sources, and it is doubtful that he contributed to the completed film. According to a 1998 documentary on the making of the “Planet of the Apes” series, Edward G. Robinson was initially cast as “Dr. Zaius” in the first film but dropped out of the cast because he was too ill to undergo the lengthy makeup applications. The documentary also noted that James Brolin tested for the part of “Cornelius,” and that Joe Canutt served as Charlton Heston’s stunt double.

According to contemporary sources, location sites for the film included Utah and Page, AZ, with the some filming being done at the Malibu Creek State Park in California, which used to be part of the Twentieth Century-Fox Ranch. According to a 25 Jun 1967 LAT article, the “capital city of the simian nation” was constructed at the Fox Ranch after “a year’s work by architects and artists.” The base of the Statue of Liberty was created at nearby Zuma Beach, according to the 1998 documentary, while the rest of the statue was superimposed using special effects matte paintings. Throughout the picture’s shooting schedule, numerous articles commented on the secrecy surrounding the set in order to protect the “shock value” of the elaborate ape makeup, as noted by a Jun 1967 HCN article. According to the HCN article, no actor was permitted to leave the set while in makeup. A 15 Jun 1967 DV article reported that no publicity stills of the sets or actors would be distributed until the film’s release. The DV article added that it took three to four hours to apply the ape makeup, with another hour required to remove it. The 25 Jun 1967 LAT article noted that of the film’s five million dollar budget, one million dollars was being spent on the makeup.

Although the onscreen credits “introduce” actress Linda Harrison, who played “Nova,” she had appeared in minor roles in several earlier films. Planet of the Apes received Academy Award nominations for Best Costume Design and Best Original Score. John Chambers received an honorary Oscar for his “outstanding make-up achievement” for creating the film’s complex makeup. In 2001, Planet of the Apes was selected for inclusion in the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry.

Four more films based on Boulle’s characters were produced by Twentieth Century-Fox, with the series becoming one of the most profitable and popular science fiction series in film history. All of the films in the series were produced by Jacobs. The second film, 1970’s Beneath the Planet of the Apes (see entry), was directed by Ted Post, starred James Franciscus and Kim Hunter, reprising her role as “Zira,” and was the only entry in the series not to feature Roddy McDowall. In 1971, the studio released the third film, Escape from the Planet of the Apes (see entry), directed by Don Taylor and again featuring McDowall and Hunter in their original roles as they traveled back in time to an Earth still ruled by human beings rather than apes. The series’ fourth entry, 1972’s Conquest of the Planet of the Apes, was directed by J. Lee Thompson and starred McDowall as “Caesar,” the full-grown offspring of Zira and Cornelius, who leads domesticated apes into a revolt against their human oppressors. Battle for the Planet of the Apes, released in 1973, was also directed by Thompson and starred McDowall and Claude Akins as opposing factions within the ape community, trying to resolve their differences and their animosity toward humans. The series spawned a highly successful variety of merchandising items. A May 1974 DV article reported that the toys, games, dolls and other articles inspired by the series were expected by the studio to gross one hundred million dollars by 1975.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Once again, thanks for your excellent contribution.

LikeLike

I am glad you like them. If you like newspaper movie ads(1931-1979), check out my X.com page – Michael Dalton@OldMovieAds. I add four new ones everyday.

LikeLike