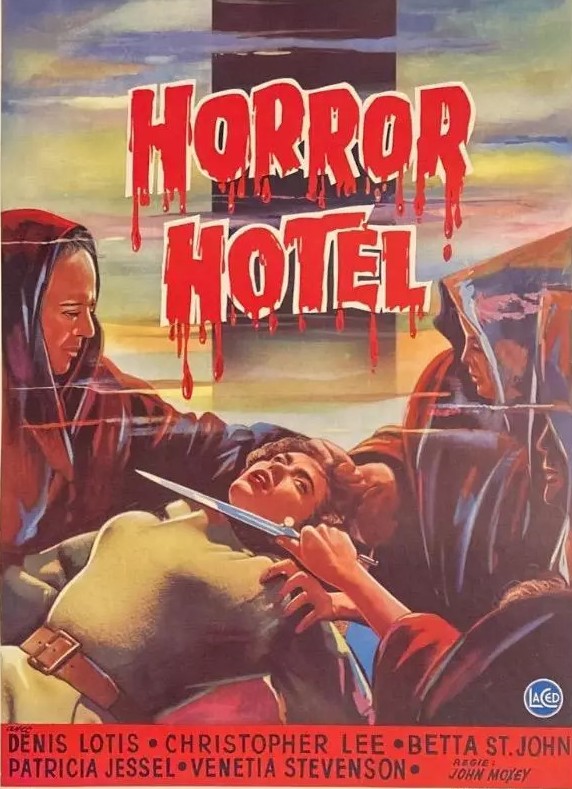

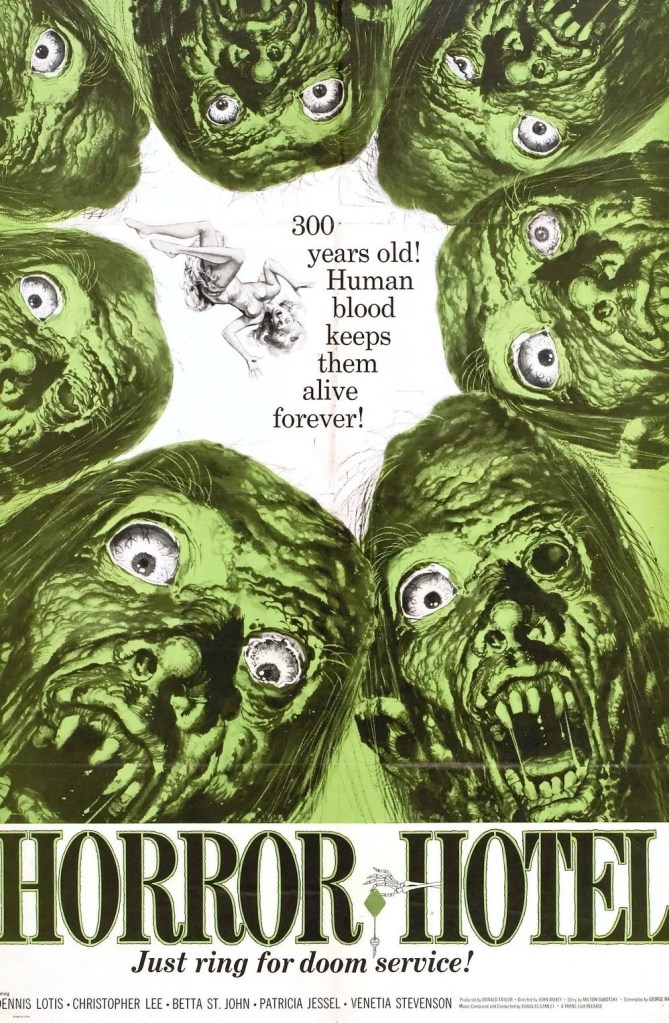

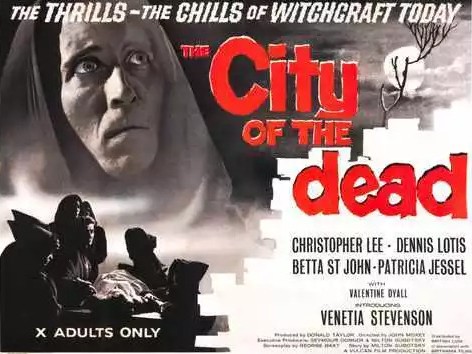

The structure of this piece gives away its origins. It’s effectively a portmanteau, though limited in this instance to three connected tales. Mention the word “portmanteau” and Amicus springs to mind. While that outfit didn’t exist at this precise moment, the movie was put together by the team behind Amicus, American producers Milton Subotsky and Max Rosenberg. The odd American accents might provide the clue that it was made entirely in Britain with British actors.

The witchcraft-zombie combo works well enough but horror mainstay Christopher Lee (Dracula, Prince of Darkness, 1966) is used sparingly. It marks the debut of Argentinian-born director John Llewellyn Moxey who has acquired something of a cult status in these parts.

We begin with a prolog set in Whitewood, Massachusetts, in 1692 at the height of the witch-burning epidemic where Elizabeth Selwyn (Patricia Jessel) is burned at the stake. Her lover Jethrow (Valentine Dyall) made a pact with the Devil to supply virgin sacrifices at a propitious time in the necromancy calendar in return for eternal life.

Three centuries later history student Nan Barlow (Venetia Stevenson), a virgin with an interest in witchcraft, sets off, at the instigation of Professor Driscoll (Christopher Lee) and against the advice of fiancé Bill ((Tom Naylor) and brother Dick (Dennis Lotis), to investigate the happenings at Whitewood. She puts up at The Raven’s Inn whose landlady Mrs Newless bears at distinct resemblance to Elizabeth.

Had this picture carried the Amicus stamp, I might have been prepared for what happened next. Nan doesn’t get much chance to do much investigation before she is burned at the stake by the coven of Mrs Newless, revealed as Elizabeth.

So we are on to the third part of the portmanteau. Dick discovers that his missing sister’s supposed abode, The Raven’s Inn, doesn’t exist in any directory, so he ups sticks and with the fiancé sets off in pursuit. Crucially, brother and fiancé, are separated, effectively allowing the stories not so much to dovetail but to keep the fiancé out of action until he is needed.

Dick makes acquaintance with Patricia (Betta St John), antiques dealer and witchcraft expert, who warns him off. Any impending romance, such as would be de rigeur in normal circumstances, is cut off after Patricia is kidnapped and set up for the virgin sacrifice ceremony.

Two virtual last-minute entrants serve to provide a big climax. Driscoll is revealed to be a member of the coven and Bill arises from his sick-bed – he was badly injured in a car crash – to save the day, despite his cynicism knowing enough of demonic folklore to bring a cross into the proceedings. This he does by the complicated process of yanking up from a graveyard a fallen large wooden cross which inflicts the necessary damage on the coven. Though Elizabeth escapes it’s not for long.

Dodgy accents aside, and slightly discombobulated by the structure, which, given it wasn’t released in the U.S. until 1962, might have been viewed as a nod to Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) in despatching the heroine halfway through, there’s enough here in the atmosphere and the performances to keep the enterprise afloat, if only just.

A good dose of fog always helps and the occasional appearance of the undead and the olde worlde atmosphere makes this work more than the acting which, excepting Lee, is on the basic side. Venetia Stevenson (The Sergeant Was a Lady, 1961) otherwise the pick.

This didn’t set Moxey on the way to fame and fortune but somehow in the world of cult less is more. He made only a handful of movies including Circus of Fear (1966). Written by Subotsky and George Baxt (Night of the Eagle, 1962).

A good first attempt at horror from the Amicus crowd.