Small wonder that Bus Riley’s Back in Town found scant appreciation on producer’s Elliott Kastner’s dance card. He preferred to have people believe that his career began with box office smash Harper / The Moving Target (1966) rather than the two flops – Kaleidoscope (1966) and Bus Riley’s Back in Town (1965) – that preceded it. As his son Dillon Kastner pointed out: “He always preferred to forget his first film. He liked to think his first film was Harper so he never put that title (Bus Riley) on his list of credits for investors.”

After jockeying in the Hollywood trenches for three years, Kastner should have been delighted to finally get his name on a picture after so many potential movies had slipped through his grasp. But he had good reason to want to forget the experience of working on Bus Riley. It sat on the shelf for a year and, minus the involvement of the producer, was “butchered” by the studio.

By the time the movie appeared it was the latest in a long line of failed attempts by former agent Elliott Kastner to get onto the Hollywood starting grid. He had previously been involved in a pair to star Warren Beatty – Honeybear, I Love You with a screenplay by Charles Eastman and Boys and Girls Together adapted from the William Goldman bestseller with Joseph Losey (Accident, 1966) lined up as director. Also on his scorecard were 1963 William Inge play Natural Affection, Tropic of Cancer from the controversial Henry Miller novel and The Crows of Edwina Hill. At the time of the Bus Riley opening, he had acquired a further seven properties.

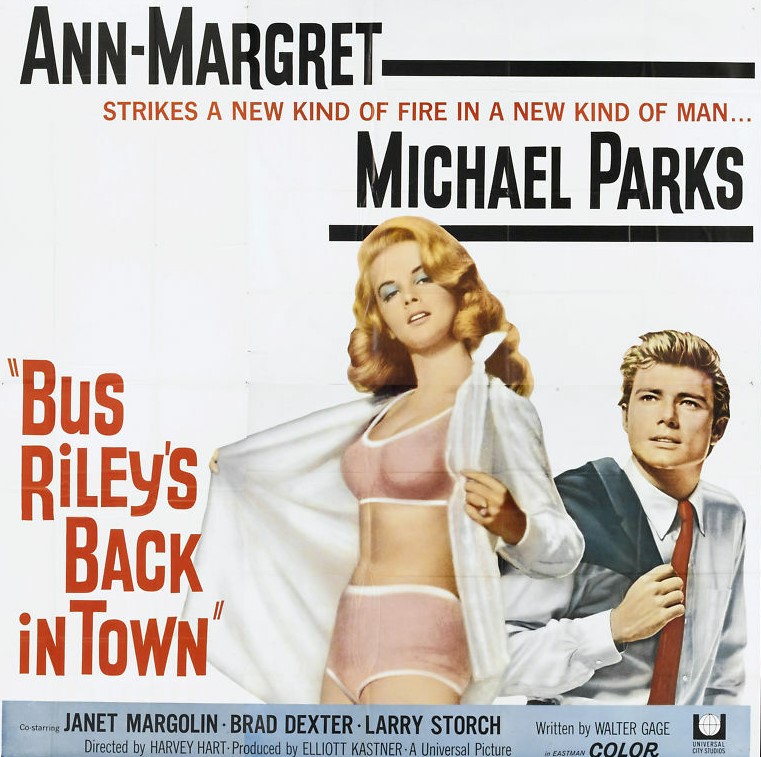

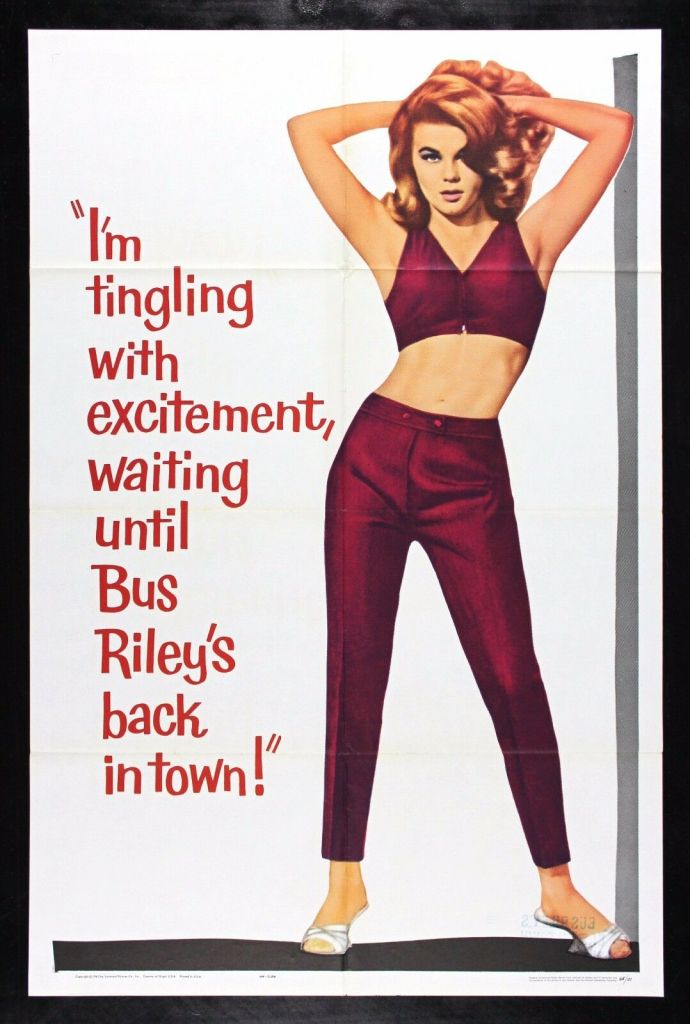

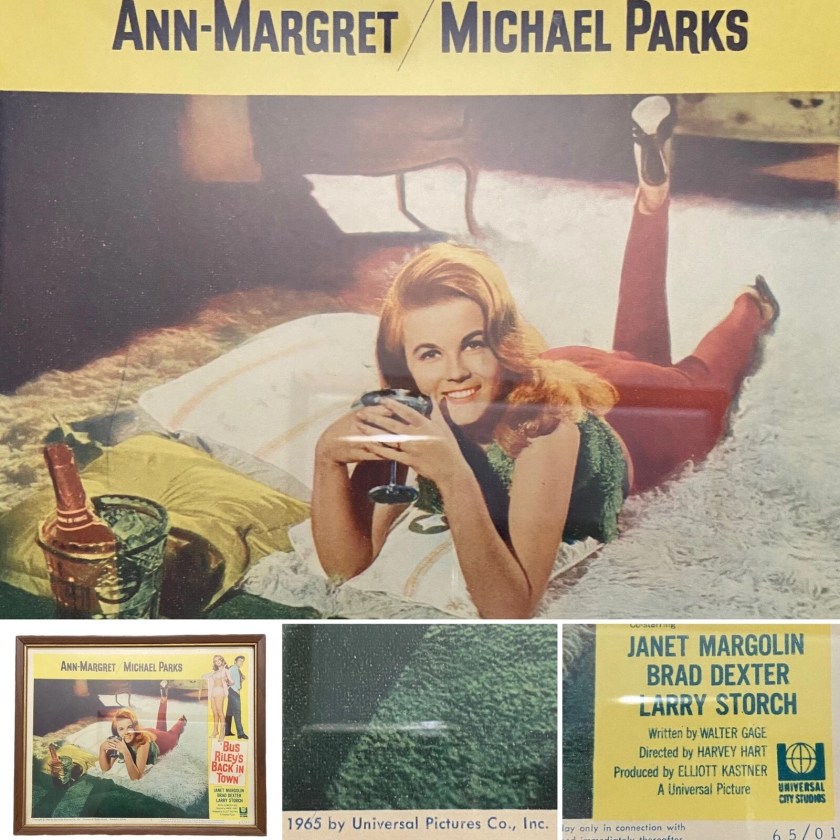

Bus Riley was never intended as a major picture, the budget limited to $550,000 – at a time when a decent-sized budget was well over $1 million. Shot in Spring 1964, and in post-production in July, release was delayed until Universal re-edited it and added new scenes because Ann-Margret had achieved surprising movie stardom between her recruitment and the film’s completion. Along with Raquel Welch, she became one of the most glamorous stars of the decade and in building up her own career Welch clearly followed the Ann-Margret template of taking on a bucket of roles and signing deals with competing studios.

After making just three movies – A Pocketful of Miracles (1962), State Fair (1962) and Bye, Bye Birdie (1963) – Ann-Margret shot into the fast lane, contracted for three movies with MGM at an average $200,000 per plus an average 12% of the profit, substantial sums for a neophyte. On top of that she had four far less remunerative pictures for Twentieth Century Fox, three for Columbia, Marriage on the Rocks with Frank Sinatra and a couple of others. By the time Bus Riley finally appeared, she had expanded her appeal through Viva Las Vegas (1964) opposite Elvis and top-billed roles in Kitten with a Whip (1964) and The Pleasure Seekers (1964).

Universal also had another property to protect. Michael Parks was one of small contingent of novice actors in whom the studio had invested considerable sums, using them in television roles before placing them in major movies. Others in this group – at a time when most studios had abandoned the idea of developing new talent – included Katharine Ross and Tom Simcox who both appeared in Shenandoah (1965), James Farentino (The War Lord, 1965), Don Galloway (The Rare Breed, 1965), Doug McClure (The Lively Set, 1964) and Robert Fuller and Jocelyn Lane in Incident at Phantom Hill (1965).

However, the introduction of Parks had not gone to plan. He was set to make his debut in The Wild Seed (1965) – originally titled Daffy and going through several other titles besides – but that was also delayed until after Bus Riley, riding on Ann-Margret’s coat-tails, offered greater potential. Kastner had been instrumental in the casting of Parks – whom he tabbed as “a wonderful up-and-coming actor” – in The Wild Seed.

Also making their movie debuts in Bus Riley were Kim Darby (True Grit, 1969) and Canadian director Harvey Hart (Dark Intruder, 1965), an established television name. Hart joined David Lowell Rich and Jack Smight as the next generation of television directors making the transition. Universal was on a roll, in 1964 greenlighting 25 pictures, double the number of productions in any year since 1957.

Falling just behind Tennessee Williams league in terms of marquee clout, playwright William Inge had won an Oscar for Splendor in the Grass (1961) and been responsible for a string of hits including Come Back Little Sheba (1952) – Oscar for Shirley Booth – the Oscar-nominated Picnic (1955) starring William Holden and Kim Novak and Bus Stop (1956) with Marilyn Monroe.

Kastner had persuaded him to turn his little-known 1958 one-act play All Kinds of People into a movie-length screenplay. Inge was initially keen to work on a low-budget picture, anticipating “more freedom with an abbreviated budget.” He asserted, “You don’t have the front office calling you up all the time.” Since the movie was not initially envisaged as a star vehicle for Ann-Margret (and, in fact, she plays the supporting role) he saw it as a “way of breaking up that old Hollywood method of selling pictures before they were made” on the back of a big star and hefty promotional budget.

Unfortunately for him, once Universal realized they had, after all, a star vehicle, the studio concluded that her image was more important than the “dramatic impact” of the film. “When we signed Ann-Margret she wasn’t a big star but in six months she was and Universal became very frightened of her public image. They wanted a more refined image.”

Kastner and Inge were elbowed aside as Universal ordered a rewrite and reshoots. Inge took his name off the picture. The credited screenwriter Walter Gage did not exist, he was created to get round a Writer’s Guild dictat that no movie could be shown without a writer’s name on the credits.

Despite her supposed growing power, Ann-Margret had little say in preventing the changes either. She expressed her disappointment to Gordon Gow of Films and Filming: “You should have seen the film we shot originally. William Inge’s screenplay…had been so wonderful. So brutally honest, And the woman, Laurel, as he wrote her, was mean and he made that very sad. But the studio at the time didn’t want me to have that image for the young people of America. They thought it was too brutal a portrayal. They wanted me to re-do five key scenes. And those scenes completely changed the story. There were two of these scenes that I just refused to do. The other three I did, but I was upset and angry.”

Film historian James Robert Parish refuted Ann-Margret’s recollection of events. He claimed the changes were made at her insistence because she wanted to be the focal point of the narrative rather than Bus Riley (Michael Parks).

Harvey Hart reckoned Universal got cold feet after the audience attending a sneak preview made “idiotic” comments on the questionnaire. Recalled Kastner, “I had nothing but heavy fiddling and interference from Universal.” Even so, given it was his debut production, he wasn’t likely to disown then and didn’t follow Inge in removing his name.

Despite the changes, the movie received a cool reception at the box office. It turned in opening weeks of a “modest” $7,000 in Columbus, “slow” $9,000 in Boston, “modest” $9,000 in Washington, “lightweight” $10,000 at the 1642-seat Palace in New York, “mild” $4,000 in Provident, “so-so” $4,000 in Portland, “not so good” $7,000 in Pittsburgh, “okay” $7,000 in Philadelphia, and $98,000 from 22 houses in Los Angeles with the only upticks being a “good” $7,000 in Cincinnati and a “fast” $7,000 in Minneapolis. The movie didn’t register in Variety’s Annual Box Office Chart which meant it earned less than $1 million in U.S. rentals and was listed as a flop.

SOURCES: Elliott Kastner Memoir, courtesy of Dillon Kastner; “Elliott Kastner’s Partner on Honeybear Is Warren Beatty,” Variety, January 23, 1963, p4; “Elliott Kastner Will Helm Crows for U,” Variety, May 1, 1963, p21; “Escalating Actress,” Variety, May 22, 1963, page 4; “Raid Canadian Director,” Variety, March 4, 1964, p24; “Inge Thinks Writer Contentment May Lie in Creative Scope of Cheaper Pix,” Variety, May 6, 1964, p2; “Ann-Margret Into the Cash Splash,” Variety, July 22, 1964, p5; “Universal Puts 9 Novices Into Pix,” Variety, March 3, 1965, p25; “ A Collective Byline,” Variety, March 17, 1965, p2; “U Stable of Promising Thespians,” Variety, March 17, 9965, p2; “Fear Ann-Margret Going Wrongo in Her Screen Image,” Variety, March 24, 1965, p5; “Radical Kastner-Gershwin Policy: Get Scripts in Shape Way Ahead,” Variety, May 19, 1965, p19; “Warren Beatty Partner and Star of Goldman Tale Via Elliott Kastner,” March 31, 1965, p7; “Picture Grosses,” Variety – March-May 1965.