With the contraction of Hollywood production in the 1960s, cinemas worldwide were always crying for pictures – any pictures – that could take up a weekly slot or pad out a double bill. (The single-bill programming that is standard these days was not welcome in most cinemas, except a prestigious few, and audiences expected to see two movies for the price of their ticket). Indie unit Mirisch had scored such a big hit with aerial war number 633 Squadron (1964) – it recouped its entire cost from British distribution so was in profit for the rest of its global run – that Walter Mirisch persuaded distribution partner United Artists to attempt to capitalize on the idea and thus set in progress a series of war pictures to be made in Britain.

There would be cost savings through the Eady Plan. Each film would have a “recognizable American personality in the lead” and have American directors. Budgets would be held under $1 million. Half a dozen movies were planned, the first appearing in 1967, the last in 1970.

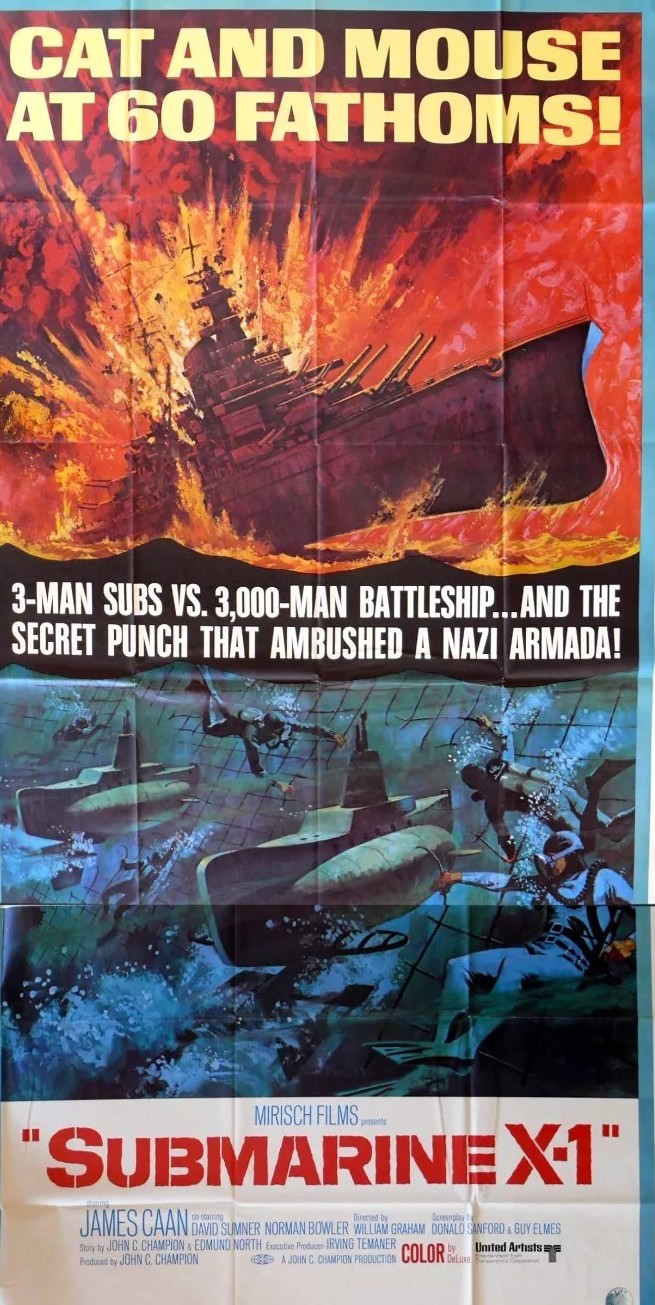

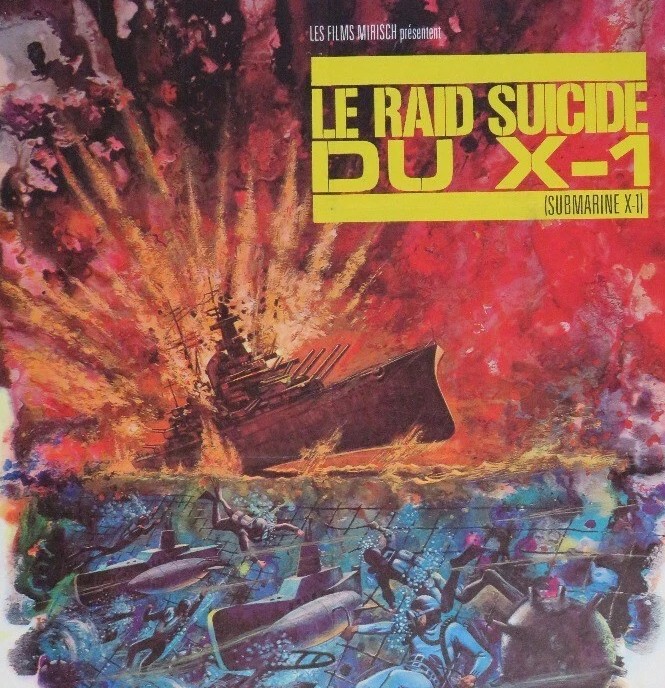

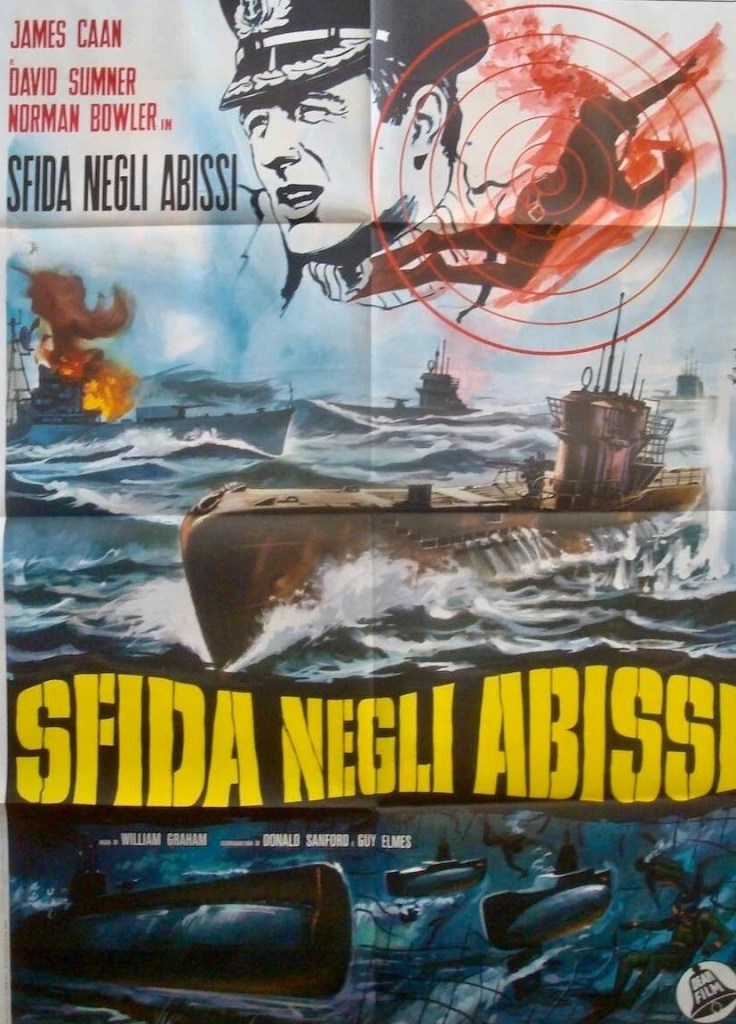

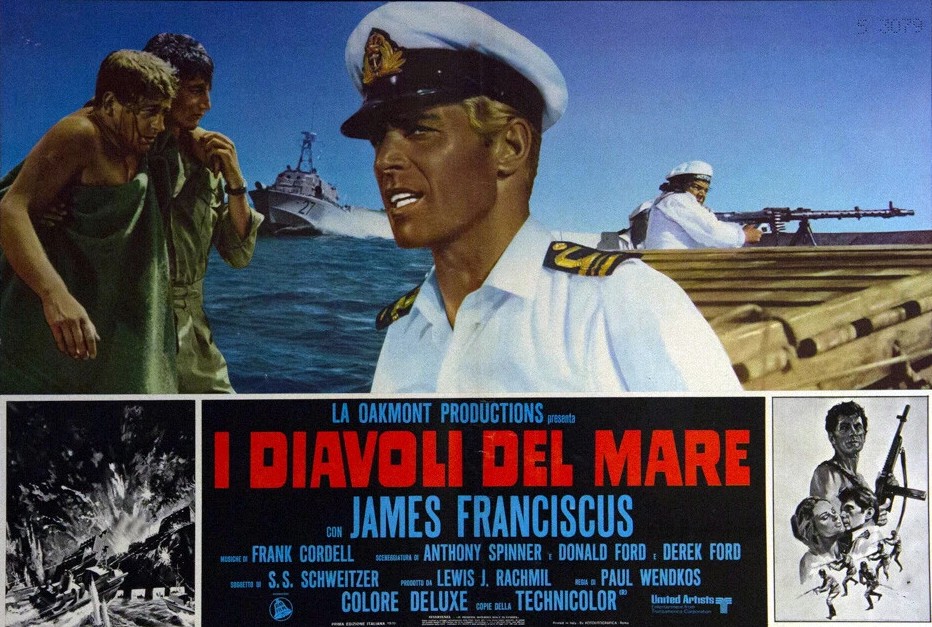

Quite whether James Caan (Red Line 7000, 1965) passed muster as a well-known enough star to qualify as a “personality” at the time he headlined Submarine X-1 (1968) is debatable, as was the presence of James Franciscus (The Valley of Gwangi, 1969) in Hell Boats (1970) and Christopher George (Massacre Harbor, 1968) in The Thousand Plane Raid (1969) though Stuart Whitman (Rio Conchos, 1964) exerted a higher marquee appeal for The Last Escape (1970). Veteran Lloyd Bridges (Around the World under the Sea, 1966) who headlined Attack on the Iron Coast (1968) was probably the best known, but these days that was mostly through television. And David McCallum owed whatever fame he had to television as part of The Man from U.N.C.L.E. double act and the idea that would still be enough to attract an audience for Mosquito Squadron (1969) seemed dubious.

Beyond setting up the project, Walter Mirisch had little to do with the actual production, putting that in the hands of Oakmont Production, which beefed up the action with judicious use of footage from other pictures. Invariably, reasons had to be given to explain why actors with American accents were members of the British fighting forces – most commonly they were represented as Canadian volunteers or might have British nationality by dint of having a British mother.

Storylines followed a similar template. At its heart was a dangerous mission. Leaders were invariably hated for some previous misdemeanor or because they were ruthless and drove the men too hard. If there was romance – not a given – it would border on the illicit. And someone required redemption.

And while none of the stars chose – or were chosen to – repeat the experience, Oakmont established something of a repertory company behind the scenes, writers, directors and producers involved in more than one movie.

for most of the films in the series.

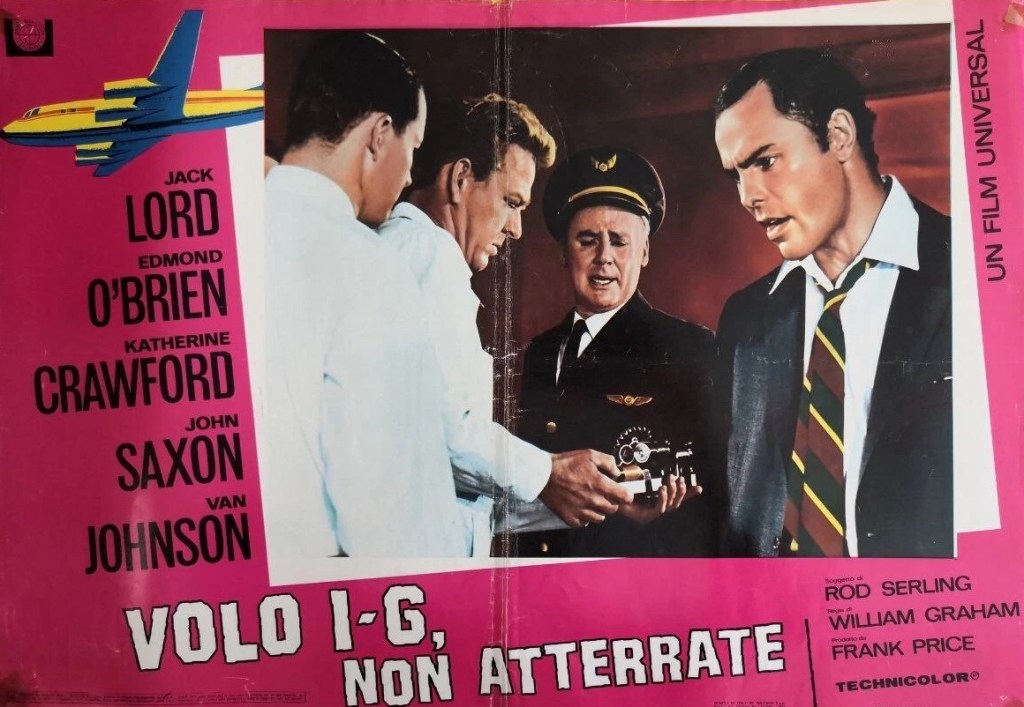

Boris Sagal (Made in Paris, 1966) directed both The Thousand Plane Raid and Mosquito Squadron and then made his name with The Omega Man (1971). Paul Wendkos (Angel Baby, 1961) helmed Attack on the Iron Coast and Hell Boats. Walter Grauman who had kicked off the whole shebang with 633 Squadron returned for The Last Escape. William Graham (Waterhole #3, 1967) as the only outlier with just Submarine X-1 to his name.

Veteran producer Lewis Rachmil (A Rage to Live, 1965) oversaw three in the series – Hell Boats, Mosquito Squadron and The Thousand Plane Raid. Another veteran John C. Champion, younger brother of celebrated Broadway choreographer Gower Champion, was involved in a variety of categories. Champion is almost an asterisk these days, best known these days for producing the film Zero Hour! (1957) that inspired disaster parody Airplane! (1980). He was only 25 when he produced his first picture, low-budget western Panhandle (1948). He was behind another four low-budget westerns pictures before Zero Hour!, which had a decent cast in Dana Andrews and Linda Darnell. But that was his last movie for nine years as he switched to television and Laramie (1959-1963), barely reviving his movie career with The Texican (1966) starring Audie Murphy.

He produced Attack on the Iron Coast and Submarine X-1 and was credited with the story for both plus The Last Escape. Irving Temaner produced The Last Escape and received an executive producer credit on Attack on the Iron Coast and Submarine X-1. Donald Sanford (Battle of Midway, 1976) was the most prolific of the writers, gaining screenplay credits for Submarine X-1, The Thousand Plane Raid and Mosquito Squadron. Herman Hoffman (Guns of the Magnificent Seven) wrote Attack on the Iron Coast and The Last Escape.

Cinema managers were not, it transpired, queuing up for the product. Most commonly, when reviewed in the British trade press, their release date was stated as “not fixed” which generally meant that United Artists was hoping the review would do the trick and alert cinema owners.

In the United States, they rarely featured in the weekly box office reports, though Portland in Oregon appeared partial to the product, Attack on the Iron Coast appearing there as support to Hang ‘Em High (1968), Mosquito Squadron supported The Christine Jorgensen Story (1970), Hell Boats supported Lee Van Cleef western Barquero (1970) while The Last Escape supported Mick Jagger as Ned Kelly (1970). To everyone’s astonishment a double bill of Hell Boats / The Last Escape reported a “big” $10,000 in San Francisco, but that proved an anomaly.

In Britain, the movies fulfilled their purpose as programmers, not good enough to qualify as a proper double bill, but accepted as supporting feature for a circuit release on the Odeon chain. Since UA supplied Odeon with its main features, it proved relatively easy to persuade the circuit to take the war films to fill out a program. This kind of second feature would be sold for a fixed price not sharing in the box office gross. However, they were given the kind of all-action poster they hardly deserved.

So in 1968 Attack on the Iron Coast went out with The Beatles Yellow Submarine. In 1969, Submarine X-1 supported slick heist picture The Thomas Crown Affair, which with Steve McQueen and Faye Dunaway in top form scarcely needed any help securing an audience. Hell Boats was supporting feature in 1970 to Master of the Islands (as The Hawaiians starring Charlton Heston was known). As well as accompanying it on the circuit Mosquito Squadron in 1970 made a very brief foray into London’s West End with thriller I Start Counting and then reappeared a few months later as an alternative choice of support for Billy Wilder flop The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes. If you went to see Burt Lancaster western Lawman in 1971 you might have caught The Last Escape – equally it could have been If It’s Tuesday, It Must Be Belgium (cinema managers could choose either).

United Artists, under the financial cost in the early 1970s, pulled the plug on “programmers” such as these. Walter Mirisch in his biography, disingenuously suggested that the six movies had done relatively well. But that wasn’t supported by the studio’s own figures.

Collectively, they made a loss of $1.7 million. Only Attack on the Iron Coast made it into the black and then by only $59,000. Hell Boats lost $700,000. None of the movies earned more than $200,000 in rentals in the United States.

Although Mirisch managed to keep budgets down to around the million-dollar mark, they would have had to be much smaller to see a profit. Ironically, it was the cheapest, Attack on the Iron Coast costing $901,000, that made the most. Submarine X-1 lost $150,000 on a $1 million budget, Mosquito Squadron lost $253,000 on a $1.1 million budget while The Thousand Plane Raid lost $50,000 more on the same budget. The longer the series went on, the worse the losses – The Last Escape lost $449,000 on a $995,000 budget while for Hell Boats the budget was $1.36 million.

SOURCES: United Artists Archives, University of Wisconsin; Walter Mirisch, I Thought We Were Making Movies, Not History (University of Wisconsin Press, 2008) p204; Reviews, Kine Weekly – Feb 9 1968, Aug 31 1969, January 1970, April 18 1970; “Flops Loss-Cutting,” Variety, August 26, 1970, p6; “Picture Grosses,” Variety – March 13 1968, May 8 1968, April 24 1968, October 2 1968, June 10 1970, July 1 1970, July 8, 1970, August 12 1970, August 26 1970.