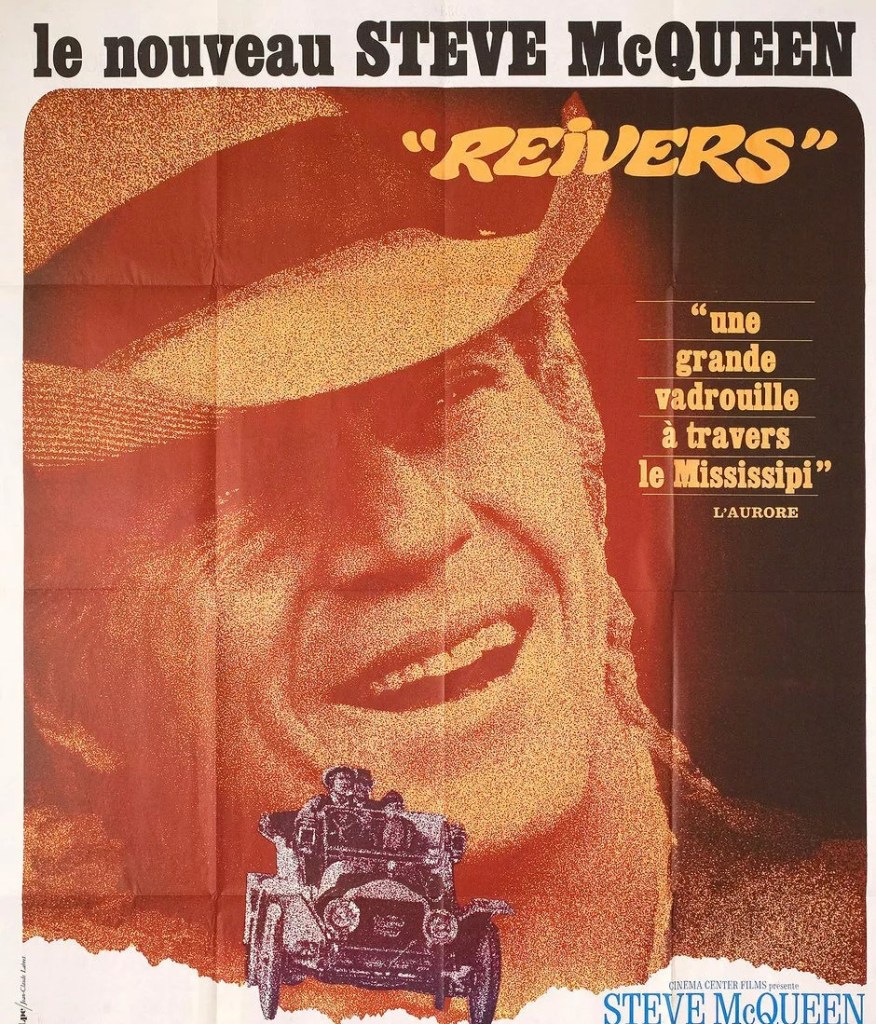

Vanity project. Two words to strike fear into the heart of a studio executive. Generally means a star has got the worthy itch. Determined to attach himself to a movie of Shakespearian proportions. Something with literary heft. Wants to break clean away from the persona that made him a star.

Experienced studio honcho, scenting red ink a mile off, rejects the proposal, or agrees to it on the condition said star first makes two, maybe even three, of the studio’s more straightforward movies. (Warner Bros had Steve McQueen on a six-picture contract). On the other hand, out there, in the Hollywood hinterland, there’s always some less well-known producer willing to pony up an enormous fee as the price of making his name. Or, in this case, a nascent mini-major, the kind that thinks it will become an ”instant major” should it sign a contract with the biggest name on the planet after the rip-roaring box office of Bullitt (1968). Step forward Cinema Center, the movie arm of CBS television, desperate to make a Hollywood splash.

Am sure the pitch wasn’t: “comedy about a thief and a sex worker.” More likely the plus point was William Faulkner, America’s most famous living writer (along with John Steinbeck), winner of the biggest award in literature, the Nobel Prize, whose short story provided the source material. Faulkner also, as it happened, had a decent movie pedigree having adapted Bogart-Bacall vehicles To Have and Have Not (1944) and The Big Sleep (1946) while an adaptation of his short stories into The Long, Hot Summer (1958) hit the box office jackpot.

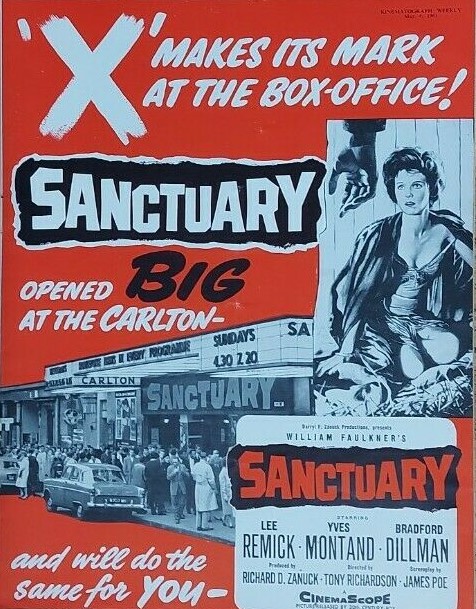

Admittedly, The Sound and the Fury (1959) and Sanctuary (1961) had been less successful, but Fox had also turned The Long, Hot Summer into a television series that ran for two seasons, so the author’s name would be fresh in the audience mind.

It’s always a worry when an actor changes his hair style. Means he’s going method or “acting.” Here, Boon (Steve McQueen) sports a bushy blond barnet. And spends most of the time in “aw shucks” mode, whirl-winding his arms, contorting his features, doing most of the things a decent director would have told any other actor to cut it out. It would take a lot more acting talent than Steve McQueen, pushing 40, can tap into to successfully convince as a guy in his 20s

At least, he’s acting enough to allow himself to be covered head-to-toe in mud, something a major star would generally avoid. The comedy is as broad as you can get and director Mark Rydell (The Fox, 1967) shows little aptitude for it, not least in knowing when to stop milking a scene.

Biggest problem is that Boon, in narrative terms, is not the star, merely the conduit. The story actually concerns 11-year-old Lucius (Mitch Vogel) growing up, as he’s lured into a scheme hatched by Boon to borrow his employer’s spanking new automobile (this is 1909, by the way) and head off for the local whorehouse. Along the way, the child becomes a jockey riding a race Boon must win.

Sex worker Corrie (Sharon Farrell) has the other major story strand and the biggest element here is the relationship between herself and the boy. When he brings out her mothering instincts, she is ashamed of her profession and she plans to quit. The boy sees a naked woman for the first time – a painting, not in person – loses his worship of Boon and doesn’t “quit” as if he’s in a hard-tack B picture.

Pretty much glossed over is the rape. You can’t have rape in a comedy, can you? But for various reasons Boon and his black buddy Ned (Rupert Crosse) and the ladies from the whorehouse have ended up in jail. Price of freedom is Corrie having sex with corrupt cop Butch (Clifton James). Corrie has the best scene, the look of humiliation on her face, when released from the cell to be raped by the cop. And this was a film sold as “a lark.”

And, of all things, Boon is purportedly in love with Corrie, but not so much that he doesn’t plan on having sex with one of the other girls, given he visits the whorehouse three times a week and Corrie, in a bit of a tizz, has turned him down.

Small wonder this has never been the subject of an anniversary revival. Hard to see how the attitudes reflected here would connect with the contemporary audience. Scarcely believable that McQueen could get himself involved, even for the privilege of being linked, at some remove, with William Faulkner.

Chances are what originated from the Faulkner pen as a more somber coming-of-age tale was altered by screenwriters Irving Ravetch (doubling up as producer) and Harriet Frank Jr (The Dark at the Top of the Stairs, 1960) to fit in with McQueen’s ambitions. The star had not wanted to make Bullitt, having an aversion to cops, and this looks like his attempt to make up for it.

Actually, it did well at the box office, Rupert Crosse and composer John Williams nominated for Oscars and McQueen and Mitch Vogel for Golden Globes.

A different McQueen, to be sure, but the subject matter is objectionable and the comedy is forced.