Hollywood hadn’t had much luck with F. Scott Fitzgerald, now considered one of the three American literary geniuses of the 20th century along with Nobel prize-winners Ernest Hemingway and William Faulkner. His novel The Great Gatsby has easily proven the century’s best-read literary novel. He was an alcoholic wastrel when in the employ of studios, in the latter stages of his life. Although The Great Gatsby had been filmed twice, in 1926 with Warner Baxter and 1949 with Alan Ladd, both versions had flopped.

His biggest seller, debut novel The Beautiful and the Damned (1922) didn’t hit the box office mark either. The Last Time I Saw Paris (1954), based on one of his short stories and starring Elizabeth Taylor, and a modest success, didn’t inspire Hollywood and it took Beloved Infidel, the memoir of his lover, gossip columnist Sheilah Graham, to kickstart further interest. But the film of that book, even with top marquee name Gregory peck, died at the box office in 1959.

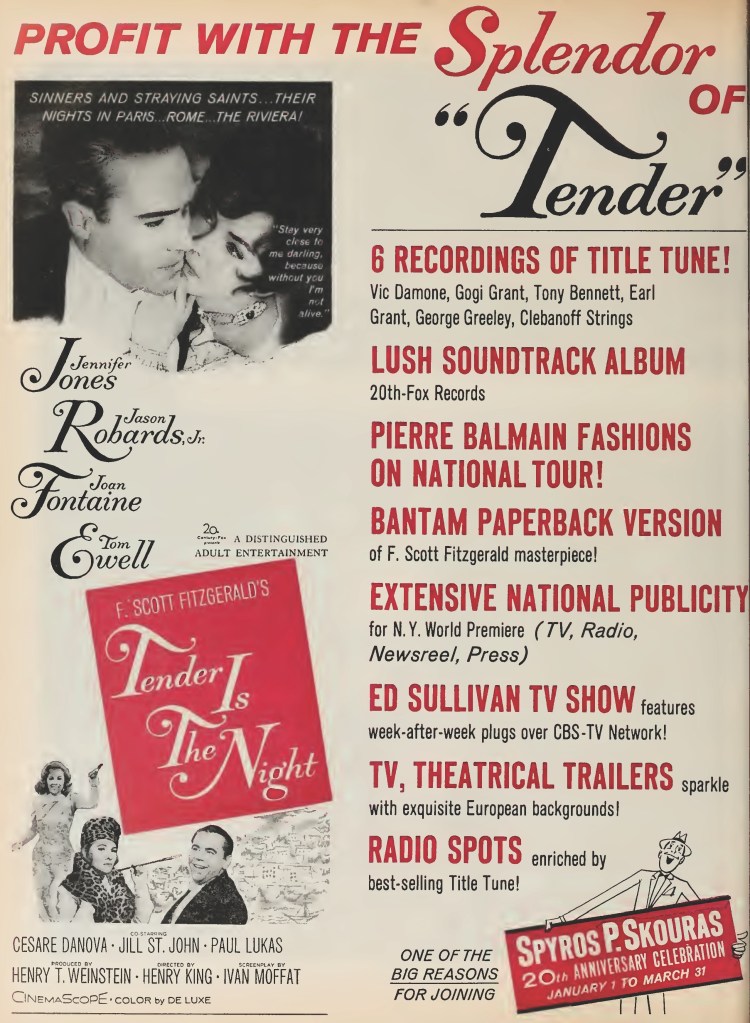

So, whatever way you cut it, Twentieth Century Fox was taking a serious gamble – the budget was $3.9 million – trying to mount Tender Is the Night especially with such questionable stars. It was a comeback for Jennifer Jones, at one time a solid performer at the box office and an Oscar-winner besides. But she had been out of the business for five years, a lifetime in Hollywood terms. Male lead Jason Robards was virtually a movie unknown. This was his sophomore outing and his debut By Love Possessed (1961) had flopped. How much his Broadway prowess would attract audiences outside the Big Apple was anyone’s guess.

But Oscar-nominated director Henry King (Beloved Infidel) who had helmed Jones’s breakthrough picture Song of Bernadette (1944) clearly thought he was on to a winner because this had the slow and stately feel – running time close on two-and-a-half-hours – of a movie that’s never going to run out of breath never mind pick up a head of steam.

Truth is, it’s slow to the point of being ponderous. Takes an age to set up the story. Psychiatrist Dr Dick Diver (Jason Robards) living with ex-patient wife Nicole (Jennifer Jones) – an arrangement that would be professionally frowned upon these days – in the French Riviera in the 1920s host a party where the husband takes a shine to Rosemary (Jill St John) and the wife shows she has not shaken off her mental malady. Despite there not being a great deal of actual period detail, we spend a long time at the party as various permutations take shape.

Then we dip into a long flashback to find out how we got here, mostly consisting of Dick falling in love with his patient, abandoning his career to enjoy a hedonistic lifestyle funded by Nicole’s wealthy sister Baby Warren (Joan Fontaine). There’s a stack of gloss. We swap the South of France for Paris and Switzerland and we’re hopping in and out of posh restaurants and hotels and the kind of railway trains that for the rich never meant a draughty carriage and hard seats.

Basically, it’s the tale of a disintegrating marriage – one that would have been better avoided in the first place as most of the audience would have pointed out – and falls into one of those cases of repetitive emotional injury. Clearly, living on his wife’s sister’s money renders Dick impotent, compounded by the loss of peer regard.

Jennifer Jones (The Idol, 1966) is pretty good, essaying a wide variety of moods, flighty, whimsical, and stubborn, exhibiting the kind of nervous energy that was implicit in her illness and which he managed to tamp down but not fully control. Jason Robards is basically on the receiving end of a character he knows only too well, and he is simply worn down by the force of her personality. So, he can’t come across as anything but pathetic, especially when he wishes to succumb to the temptations of the likes of Rosemary.

For all the strength of his usual screen persona, Robards is miscast. He doesn’t command as he needs to in order for the film to work and for the audience to sympathize with his downfall. At this stage of her career, Jennifer Jones was so far more accomplished it doesn’t take much, even when she’s not letting fly, for her to hog the screen at the expense of a balanced drama. There’s a twist in the tale but by the time that comes we couldn’t care less.

In a less showy role than was her norm, Jill St John (Banning, 1967) is effective.

Ivan Moffat (The Heroes of Telemark, 1965) wrote the screenplay. A box office disaster, it only hauled in $1.25 million in U.S. rentals. Henry King didn’t direct another picture.

Trimmed by 30 minutes, this would have been more effective.