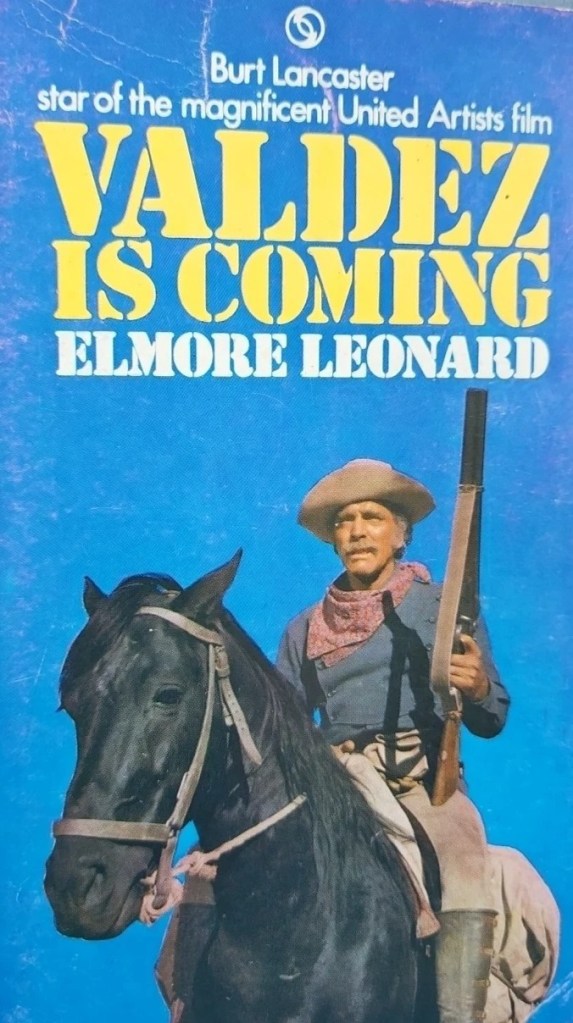

Elmore Leonard novels were catnip to the movies. From The Tall T (1957) and 3:10 to Yuma (1957) a shelf load of his books have been filmed by Hollywood – some of them (3:10 to Yuma, 52 Pick Up, The Big Bounce, Get Shorty) twice. What he brings to the table is a lean story and an interesting lead character, whether in the western – Hombre (1967), Joe Kidd (1972) – or crime division such as Mr Majestyk (1974) or Get Shorty (1995).

What you probably don’t realize is that pulp fiction (books that made their debut in paperback) were generally short, limited to 50,000-60,000 words rather than the 120,000-150,000 blockbuster “airport” novels, published first in hardcover, that dominated the bestseller lists. The shorter novel led to a leaner narrative, less characters, little in the way of subplot and information drop.

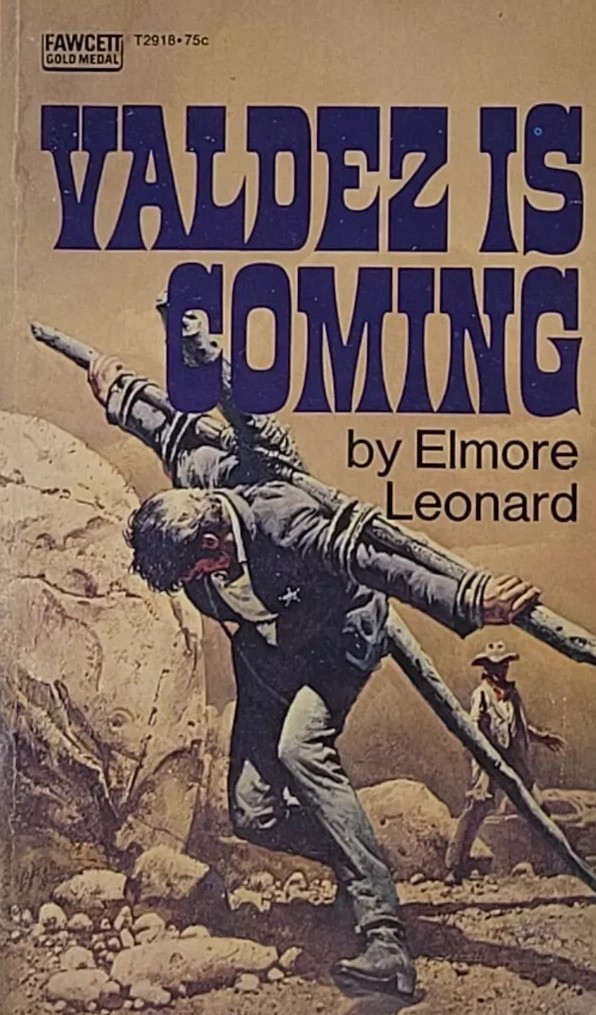

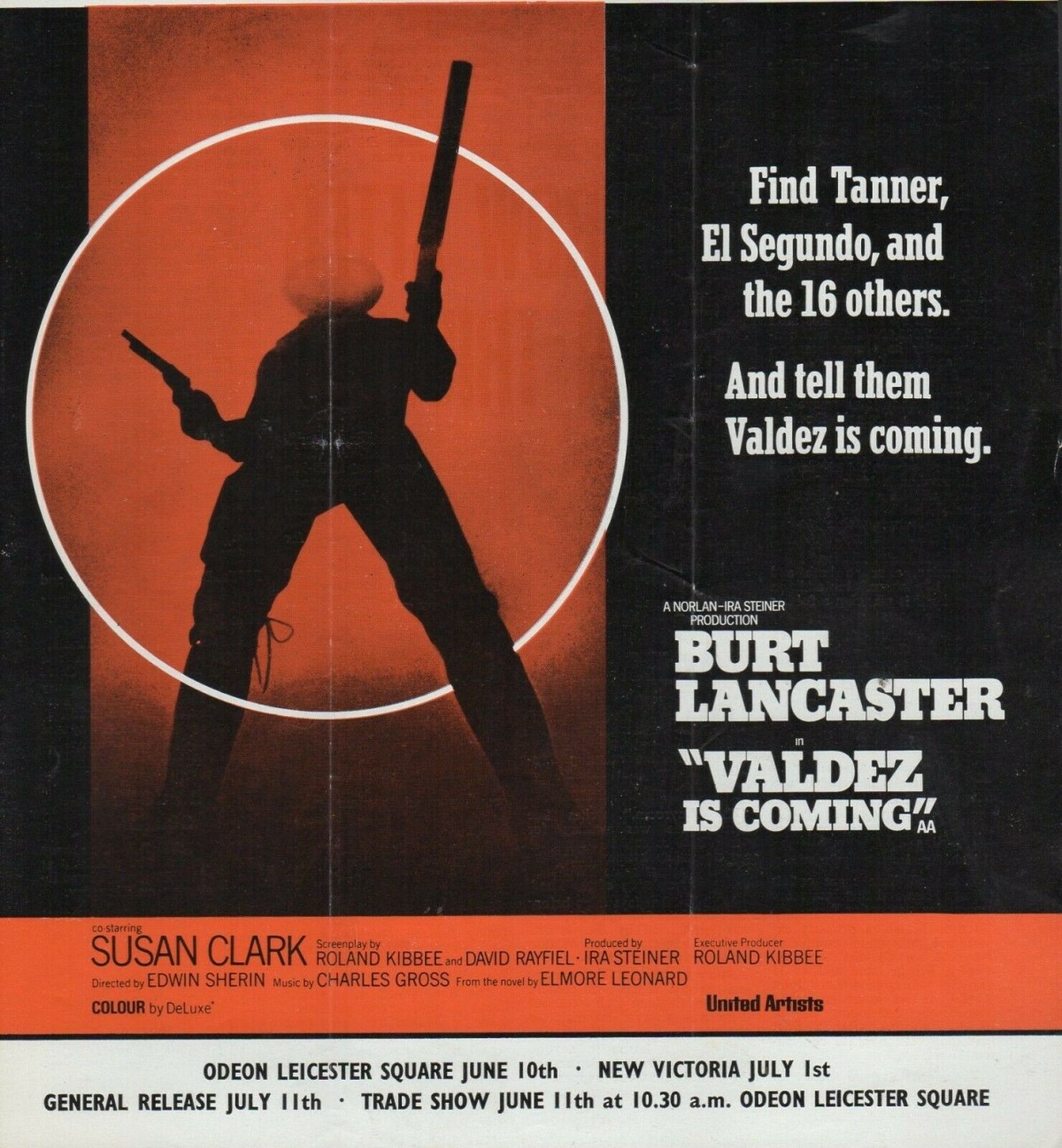

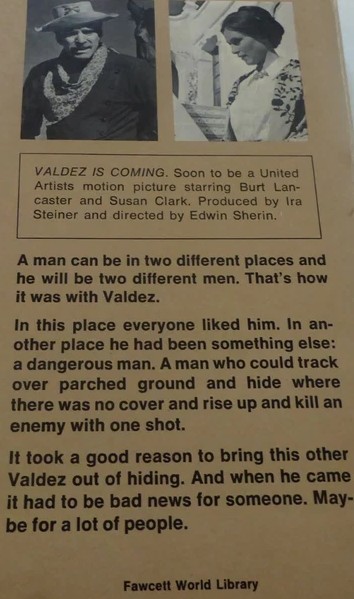

Valdez Is Coming made a speedy transition from paperback (published by Fawcett in the US in 1970, though it did achieve a hardcover edition in the UK) to movie (United Artists release 1971) and it’s interesting to see what changes, if any were made by screenwriters Roland Kibbee (The Appaloosa, 1966) and David Rayfiel (Castle Keep, 1969). You could literally transpose Leonard’s dialog and it would easily stand up in a movie. So the basic, very simple, plot is retained.

Mexican sheriff Valdez (Burt Lancaster in the film) gets it into his head that the mistaken killing of an African American requires monetary compensation and determines that cattle baron Frank Tanner whose mistake led to the killing should be the one to cough up. Tanner sees is differently, sends Valdez packing and when the sheriff returns a second time to plead his case exacts brutal punishment in the form a rudimentary crucifixion.

This triggers a personality change in Valdez. He reverts from being the subservient suit-wearing lawman to the feared sharpshooter who previously hunted down Apaches.

So one of the alterations in the book to film is this transition. In the book we know from the outset he has kept buried his older self in order not to attract attention and to live a peaceful life. That is verbalized via internal monologue and a scene with brothel keeper Inez, who is absent from the film. In the movie his past is visualized, as he pulls out from under his bed a hidden armory and a photo of his previous self.

In the film he is introduced riding shotgun on a stagecoach. He works part-time as a “constable” rather than a sheriff. In the book riding shotgun is the bigger job, keeping the peace requiring little of his time.

All the main incidents – initial rebuff by Tanner, the shooting of bullets around Valdez, the crucifixion, the kidnapping of Tanner’s wife Gay (Susan Clark), the involvement of wannabe gunslinger RL Davies (Richard Jordan), the picking off one-by-one of Tanner’s men and the final stand-off (a Mexican stand-off if ever there was one) – come straight from Elmore Leonard.

But the screenwriters make some critical changes. In the film the kidnapping is accidental, Gay snatched as a hostage as Valdez escapes from a gunfight at Tanner’s house. In the book, there’s no shoot-out at the house, Valdez kidnaps Gay in order to have something to trade with.

In the film it’s – rather surprisingly given his role so far – the weaselly gunman Davies who cuts Valdez free of the bonds of the crucifix. But that’s a considerable simplification from the book. For quite a long time in the book, Valdez believes that Gay cut him loose. And until Davies challenges that assertion, she lets Valdez believe it was her.

For the biggest change is the screenwriters’ decision to eliminate the Valdez-Gay romance. After being captured, in the book she makes overtures to him, whether initially out of survival instinct is unclear, and they make love and he begins to fall for her. We learn why she killed her husband – domestic abuse. Also that Tanner is a convicted felon and that he is a gunrunner supplying arms to Mexican rebels.

So by the time we come to the end there’s more riding on it in the book. Tanner is left isolated not just by his gang boss backing off but by his lover siding with Valdez.

One other point, I noted that in the film the guy called El Segundo (Barton Hayman) was referred to as “the segundo” (in lower case letters) in the book. So I looked it up. Literally, “Segundo” means “number two” which made sense either way.

I’ve been so used to comparing blockbuster novels with their movie adaptation and trying to work what they kept in – and why – that it never occurred to me that one of the reasons so many pulp fiction books were purchased by the movies was because screenwriters had to tussle with less plot and fewer characters.

If you’ve never read any Elmore Leonard this is as good a place as any to start.