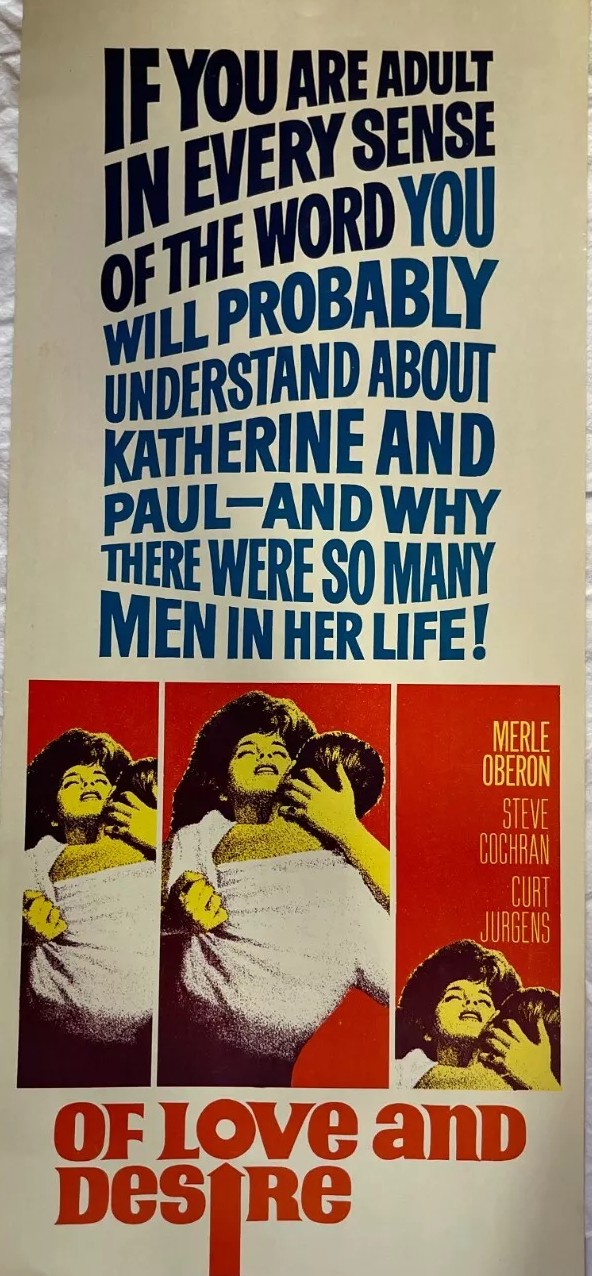

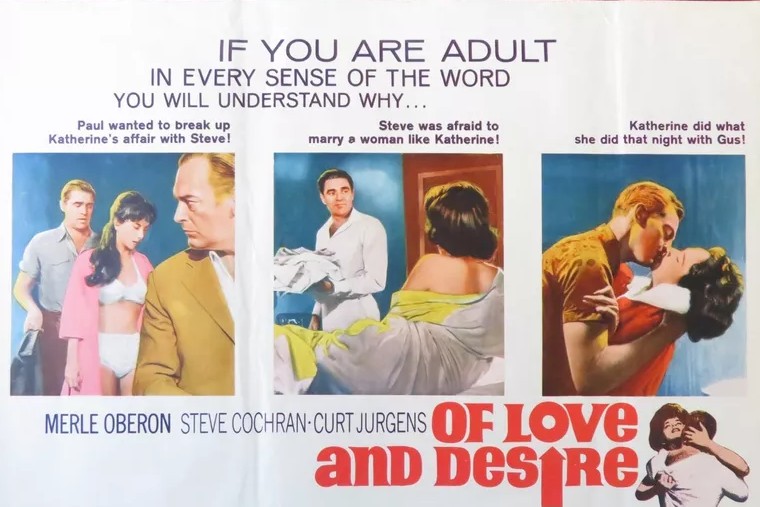

As contemporary as you could get with the core theme of a sexually independent woman picking and choosing her men. Otherwise, a smorgasbord of talent. Star Merle Oberon (Hotel, 1966) hadn’t appeared in a movie in seven years, for co-star Steve Cochran (Tell Me in the Sunlight, 1967) the screen absence was two years, Curd Jurgens (Psyche 59, 1964) was still very much a jobbing actor restricted to playing good and bad Germans, and director Richard Rush (Psych-Out, 1968), in his sophomore effort, was as erratic in the early part of his career as he would be in his later (six years between Freebie and the Bean, 1974, and The Stunt Man).

Of course, this being a somewhat mealy-mouthed decade, psychological mumbo-jumbo was required to explain the woman’s actions rather than the notion that a woman could enjoy being sexually unrepressed and free of desire for marital security. So if you manage to separate the actual movie from the required fitting-in to moral standards, it’s a darned interesting examination of the kind of free spirit later exemplified by Darling (1965) or Modesty Blaise (1966).

Mining engineer Steve (Steve Cochran) on a job in Mexico begins an affair with wealthy Katherine (Merle Oberon), half-sister of his employer Paul (Curt Jurgens). There’s nothing of the usual will-she-won’t-she in this romance, she virtually flings herself at him. Not only that, the morning after, she arranges for all his belongings to be shipped to her splendid mansion, proof of who is usually in control. Just as, more traditionally, males are instantly aroused by beautiful women, she is excited in the presence of an attractive man and makes no bones about it, not too bothered about consequent scandal even though she does her best to keep her activities discreet.

Paul isn’t so happy with the affair. He clearly prefers her unhappy and dependent on him for emotional support. And a bit like Julie in Steve Cochran’s later picture Tell Me in the Sunlight, there’s certainly an assumption that she jumps from man to man, though out of boredom rather than financial security.

So Paul sets out to sabotage the affair by putting in Katharine’s way previous boyfriend Gus (John Agar) who feels he is owed some sex and is determined she repay the debt. Although she almost succumbs and is subsequently ashamed of how easily her desire is inflamed, she resists and after he has had his way with her attempts to commit suicide.

But the question of rape is never raised and to Steve it appears she has merely resorted to type, falling into bed with the closest man. And in the time it takes to resolve the situation, we are treated to the psychological mumbo-jumbo which falls into two parts. In the first place, there has clearly been a strong sexual attraction between Paul and Katharine, and the strength of their emotional bond is in some ways a substitute for not indulging in incest. Secondly, her fiancé, a fighter pilot, was killed in the Second World War. Based on no evidence whatsoever, she has convinced herself that he committed suicide because she refused to have sex with him before marriage. To make up for that, she gives herself to any man who comes along. Yep, claptrap with a capital C. Which somewhat torpedoes the picture, which had been heading comfortably towards a feminist highpoint.

Merle Oberon almost turns the clock back a couple of decades to Wuthering Heights (1939) and her role there in physically expressing forbidden desire. You can almost feel her quivering with pent-up sexuality and she is unexpectedly superb, in what is essentially a B-picture, especially as the opportunity to tumble into melodrama – which she can’t escape in the final act – so obviously beckons. That the first two acts work so well is primarily down to her believable characterization. And Steve Cochran is no slouch either, shaking off the coil of his pervious incarnation as a tough guy. Curt Jurgens is creepy and sinister.

Director Richard Rush manages to hold his nerve until the end and then it all runs away from him into turgid melodrama. Screenplay contributions from the director, producer Victor Stoloff, Jacquine Delessert in his debut and Laszlo Gorog (Too Soon to Love, 1960, Richard Rush’s debut)

Nearly but not quite a feminist breakout.