She sings, she dances, she shakes her booty. What else would you expect from Ann-Margret in light comedic mode (i.e. The Swinger, 1966) rather than serious drama (i.e. Stagecoach, 1966). While appearing as free-and-easy as in The Swinger, she’s actually a dedicated virgin, as was par for the course before the Swinging Sixties kicked in. But the way she lets it all hang out, you’d be forgiven (if you were a predatory male) for guessing the opposite.

Maggie (Ann-Margret) is a career girl, assistant fashion buyer in a New York store, having come up the hard way, small-town-girl then model then salesperson. When the Paris buyer Irene (Edie Adams) quits her job to get married, Maggie is shipped out as her replacement, not as a reward for all her hard work but as punishment because she refuses to sleep with the boss’s cocky son Ted (Chad Everett). The idea is she’ll be so out of her depth, she’ll return humiliated and only too happy to jump into bed.

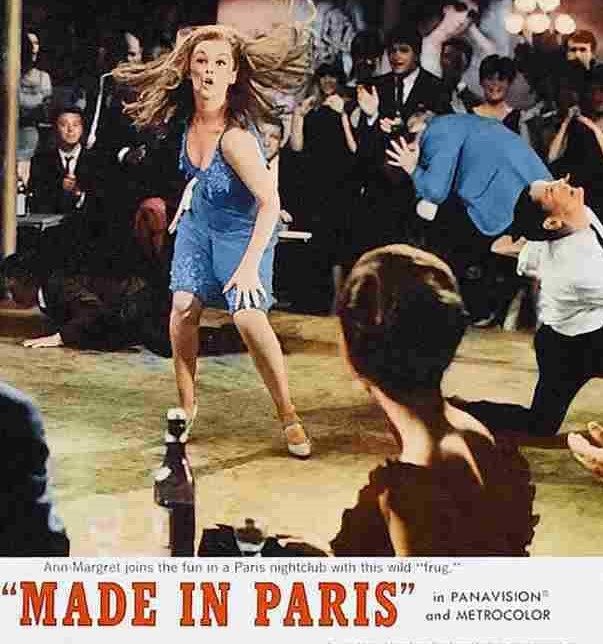

In the movie Ann-Margret dances in blue. In the poster, the dress turns red.

Turns out Irene quit so fast she didn’t have time to tell her Parisian boyfriend and fashion designer Marc (Louis Jourdan) so on Maggie’s first night in the company’s luxurious apartment he turns up. Naturally, he expects a bit of the old-fashioned quid pro quo, je ne sais quoi, whatever they call sex when they are being coy about it, and when she refuses to play ball he cables New York to demand her dismissal. Even when the New York boss (John McGiver) relents, she is banned from Marc’s fashion shows, meaning she can’t buy clothes she is forbidden to view.

Enter Ted’s buddy Herb (Richard Crenna), from the same lothario mold. Just to even things up or add further complication, Ted realizes he is actually in love with a girl who said no after a thousand boring girls who said yes. Trying to win her way back into Marc’s good books, with Herb as her guide she tracks the designer through the night clubs, eventually putting on the kind of sexy wild impromptu dance exhibition that the more staid Maggie could only have achieved if she’d taken lessons from Ann-Margret.

That does the trick and they share an impromptu number (“Paris Lullaby”) on the banks of the Seine although Marc still insists she shed her inhibitions before marriage if she wants to be considered a true Parisienne. The arrival of Mark and then Irene, abandoning her husband on their honeymoon when called in to retrieve the situation, adds fuel to the fire and then it’s one mishap after another, especially when Maggie discovers the pleasures of absinthe and ends up in Herb’s bed (yep, she has a hell of a time wondering not just how she got there but if, Heavens to Murgatroyd as Snagglepuss would say, she committed the terrible deed).

Unbelievably, and just as well perhaps from the narrative perspective, Herb isn’t a love rival. Maggie isn’t his type, its transpires. Shoot that man on sight – doesn’t fancy Ann-Margret? Lock him up!

You won’t be surprised to learn that it all sorts itself out in the end but you might be a bit taken aback how quickly a dedicated career girl throws away her career once a marriage proposal comes her way.

You might have expected from the title that Maggie would be a model, the best excuse you could find for the actress to cavort in a series of skimpy costumes, as she does in the pre-credit sequence, an exquisite dialogue-free montage with a clever pay-off that makes you think this is going to be much more stylish – excluding the fashion show of course – than it is.

Ann-Margret has such a dazzling screen persona she makes light work of even the lightest of confections. She does all that her most fervent fans would want but it’s not her fault she’s been cast in a Doris Day comedy that ensures she can only properly express her character by acts of exhibition. Louis Jourdan (Can-Can, 1960) keeps creepy entitlement at bay with lashings of Gallic charm. Despite his character’s playboy tag, Chad Everett (The Impossible Years, 1968) is the squarest of squares.

Richard Crenna (The Midas Run, 1969) spins his normal hard-ass screen persona into something a bit more sympathetic. Edie Adams (The Honey Pot, 1967) and John McGiver (Fitzwilly/Fitzwilly Strikes Back, 1967) add a bit of dash in support.

You’d never guess the director was Boris Sagal of The Omega Man (1971) fame. Stanley Roberts (Come September, 1961) wrote the screenplay.

Ann-Margret at her zingiest. What more could you ask?