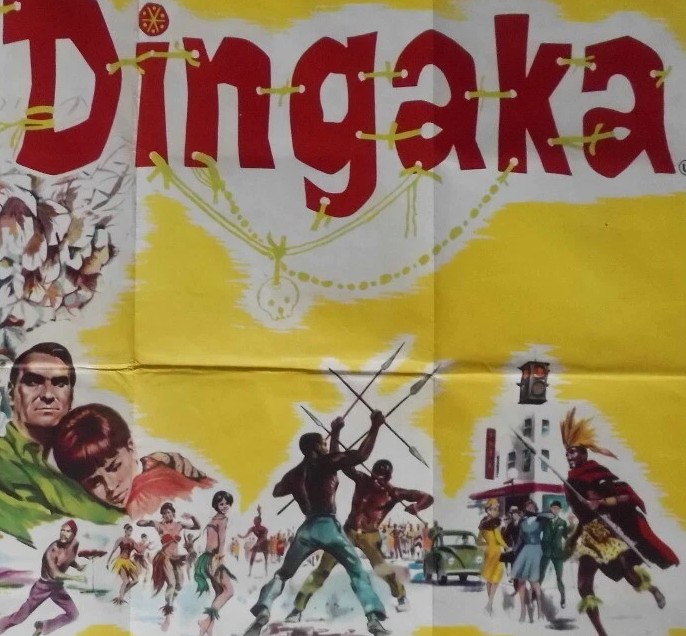

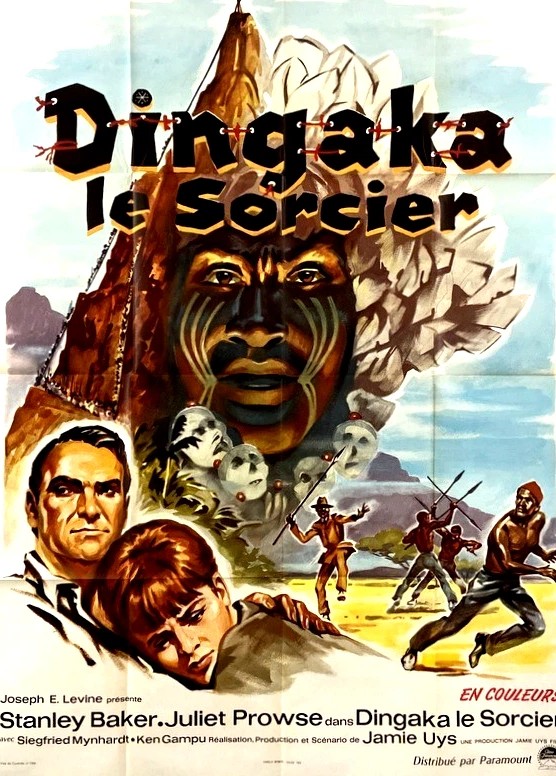

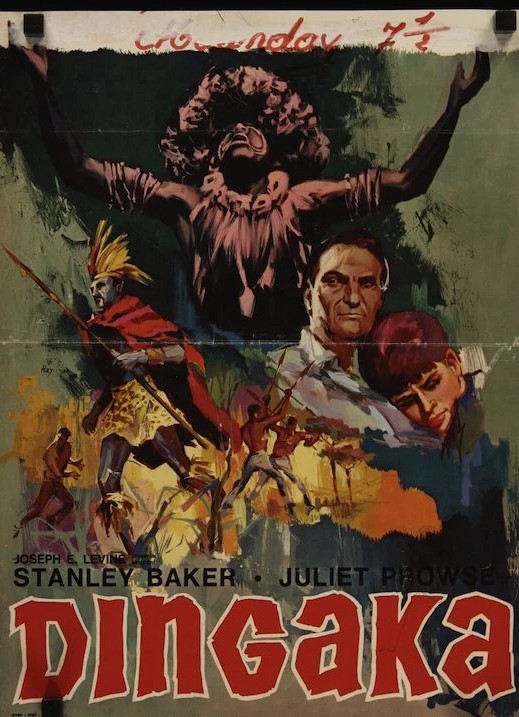

Whether you appreciate this will depend on whether you were attracted by the prospect of an early offering by South African writer-director Jamie Uys (The Gods Must Be Crazy, 1980) or by the star wattage of Stanley Baker (Sands of the Kalahari, 1965) or perhaps by the promise of the salacious. Hopefully, it was the first, because you would be disappointed on the other two counts, Baker not making an entrance until halfway through the picture and not much of an impact thereafter.

Surprisingly relevant due to its depiction of people in the thrall of a higher power – whether you take that in a religious or political context makes little difference – and in the cultural conflict between an indigenous tribe and the “civilized” white man. But there’s also a noir tone here, the fatalism that often prevents the “good criminal” in a noir picture from escaping the judicial consequence of an action that could be seen as moral.

And if you think you know your African music through interpretations by the likes of Neil Diamond and Paul Simon, then here’s a far better introduction. Song is a constant whether for ceremonial purpose, worship, entertainment and work or for making more bearable time spent in jail or hard labor.

And though it’s not spelled out there’s a Biblical element, the old “eye for an eye,” done away with in modern civilization through courtrooms, juries and due process whereby the act of killing is carried out remotely by the state rather than the victim’ relatives.

An African tribesman Masaba (Paul Makgopa), furious at being dethroned after a six-year reign as the local fighting champion, seeks a cure for the loss of prowess from a witch doctor (John Sithebe). He is told to eat the heart of a small child. Soon after the daughter of Nkutu (Ken Gampu) is found dead. The distraught father beats the witch doctor until he points to Masaba. In revenge for Nkutu assaulting the witch doctor, revered as a local god, Nkutu is cursed, resulting in the almost immediate death of his wife.

Nkutu pursues Masaba to the city and strangles him to death. He is taken aback to be arrested since, according to tribal law, he is well within his rights. Of course, that’s at odds with civilized law. When the judge learns of the murder of Nkutu’s daughter and advises that the state would take care of any killing in the way of punishment that had to be done, Nkutu is puzzled. “You must not hang him. He did not kill your child. I must kill him. It is the law.”

It turns out Masaba has survived, giving Nkutu, on meeting him in court, a second chance to kill him, which fails.

“Big hard cynical lawyer” Tom (Stanley Baker), grudgingly doing pro bono work, has his work cut out since Nkutu refuses to give him instruction, is defiantly unremorseful, and can’t provide any proof that Masaba murdered his daughter beyond that “his eyes told me that he killed her.”

But since Nkutu only attempted murder then he gets off with a relatively light sentence, though it still involves back-breaking work. But at least it’s outside, providing the opportunity to escape and go home and kill Masaba properly. Meanwhile, Tom has chanted his tune and tries to help Nkutu by confronting the witch doctor.

Eventually, Nkutu learns the witch doctor was the murderer and despite fear of being eternally cursed challenges the witch doctor’s authority and kills him. And given this takes place away from civilization it’s unlikely that anyone’s going to come asking questions.

Outside of the drama and the culture clash, the director keeps this perpetually interesting by adding in authentic aspects of local life. There’s a milk tree, a man cures hides by spinning them on a rock that dangles from a tree on a rope, access to the otherwise inaccessible witch doctor’s lair on a mountaintop is via a series of vertigo-inducing ladders, prison guards have spears not guns. The use of music adds atmosphere.

And the acting is good, and as a consequence of this Ken Gampu enjoyed a Hollywood career in such films as The Wild Geese (1974) and ended up with over 80 film credits. Stanley Baker’s character is well drawn, exchanging barbs with his wife (Juliet Prowse) his cynicism in part due to the couple’s fertility problems.

Now warned about the limitation of Baker’s involvement, if you are happy to examine the tale as presented – one of struggle against both malicious and just authority – you will be rewarded.

YouTube has a decent print and not one marred with advertisements.