It wasn’t just that Alfred Hitchcock broke all the rules in Psycho, turning horror on its head with the shower scene, introducing themes like mother-fixation and cross-dressing and delivering the first bona fide serial killer to American audiences.

He also took on the exhibition business by insisting that nobody was allowed into theaters after the film had started.

This went completely against the way films were normally shown. Patrons were accustomed to entering a movie theater whenever they liked, be it beginning, middle or end and then staying on till they came to the section they had seen before. Hitchcock was effectively calling an end to this practice.

Exhibitors were so used to customers going to the movies as a matter of course, as a regular habit, that few cinemas outside of arthouses and those in city centers even bothered to list start times. Although tacitly endorsed by exhibitors, this system was a menace to business since there was no way of knowing how many people were likely to vacate their seats at any given time and the fact that they did so intermittently interrupted the viewing of those still watching the picture.

Exhibitors were already investigating new methods of keeping their customers, including setting up their own production companies and buying up old films to present as reissues to make up for the shortage of new movies.

The Psycho “see it from the beginning” gimmick was initially viewed as exactly that – a gimmick. But when customers obliged without any particular fuss, standing patiently in line in the lobby or outside while one show vacated, this seemed to many indicative of a change in audience perspective. Many exhibitors wanted to take advantage of the potential to change moviegoing habits.

“A new concept in motion picture promotion – building appreciation of the merchandise by customers – is being undertaken by segments of the industry,” said Hy Hollinger in Variety. “The idea involves a revolutionary change in the presentation of films in theaters with the industry engaging in a vast educational campaign to indoctrinate the public.”

“The public must be taught to accept starting times,” became a mantra. A more orderly approach would lead to greater appreciation of the films being screened. For once, America wanted to follow the Europe. A system of fixed schedules operated in Europe.

There were already “significant signs that the public prefer to see pictures from the beginning.” Exhibitors had registered more telephone calls asking about start times and more tickets were being sold just prior to the film beginning.

The Psycho sensation had kicked off another experiment. The film was being shown in New York nabes concurrent with its ninth week in first run at the DeMille and Baronet theaters in Manhattan. Usually, films were clear of first run commitments before launching on the circuits.

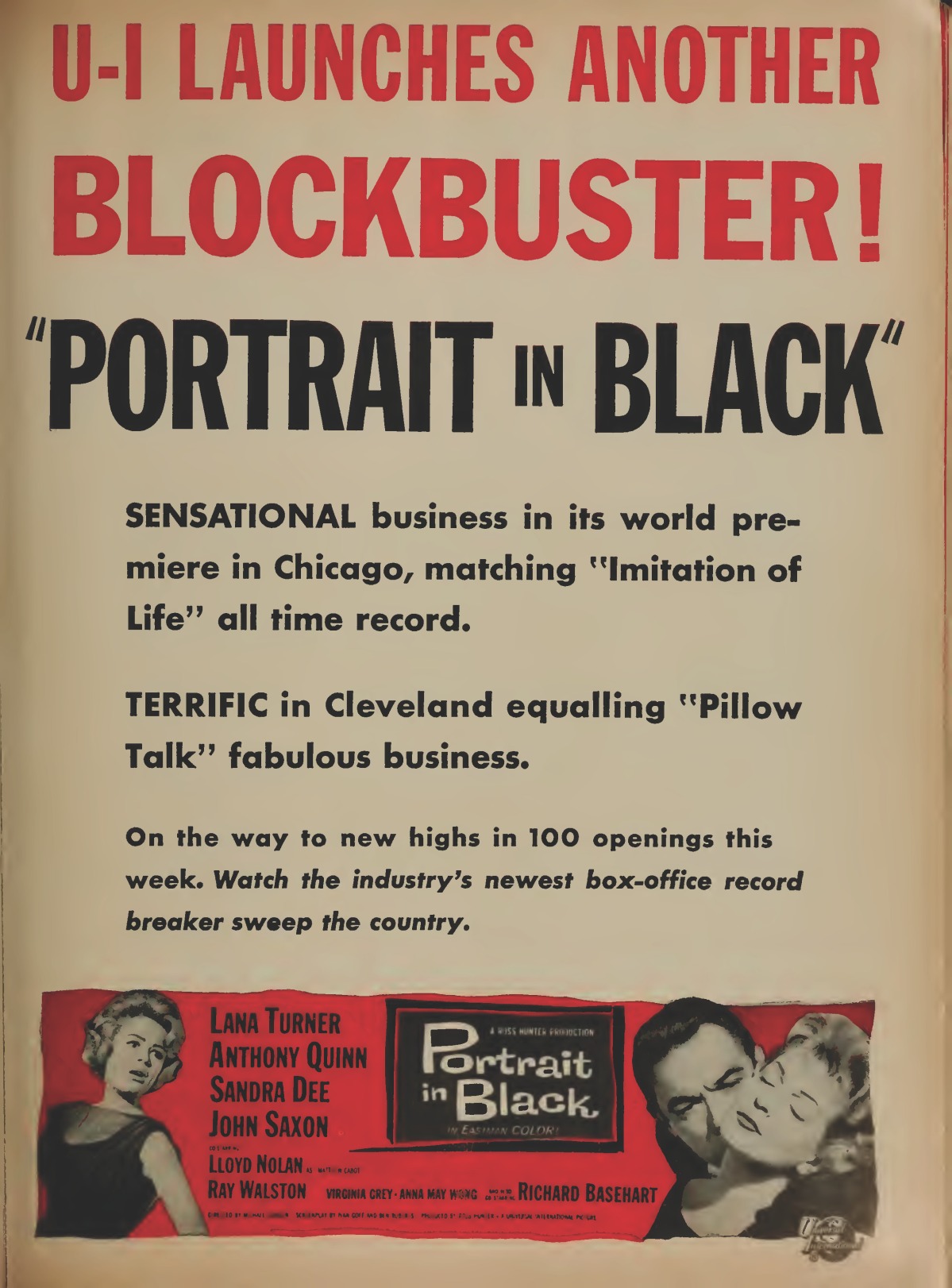

And there were yet other changes afoot. Two circuits in New York – Loews and Century – had shifted back the start time of the main feature from 10pm by an hour or more, in the case of Century to a fixed 8.40pm which allowed moviegoers to get home in time for the eleven o’clock news. New York also led the way in combining first run in big Broadway houses with a concurrent booking in an eastside arthouse – Sons and Lovers (the only genuine arthouse offering), Psycho and Portrait in Black among those benefitting from the practice.

In addition, Psycho was considered responsible for another psychological phenomenon. It was asserted by Paramount publicists that the long lines of people standing outside the theater waiting to see the film “plants in people who had no desire to see the picture the seeds of desire to do so.”

Eroding the double bill mentality was also seen as a way of setting a more rigid approach of start times. The double bill was already under pressure because the number of movies being made was much lower than a decade before. Some theaters had taken to augmenting a single bill with a 30-minute short rather than a full feature.

Arthouse audiences had already accepted that the price of their ticket entitled them to only one movie, not two. Single bills allowed a theater more showings during the day, thus increasing potential receipts. When Psycho went into the circuits it was as a single bill with five or six showings scheduled.

The roadshow was still in its infancy, Ben-Hur and a handful of other films leading the way, although spectacles like Spartacus, Exodus and The Alamo were on the horizon. Roadshows were presented as separate performances so no waste of seating capacity.

Roadshows and a film like Psycho had something else in common that augured well for a future where “grind” was eliminated. People accepted separate performances for roadshow or an uncommonly attractive feature like Psycho because they wanted specifically to see those particular pictures, not because they routinely went to the movies with little regard for what was actually being shown.

In just 38 weeks in a limited number of theaters presenting the picture in a limited number of showings at a set start time, Ben-Hur had already taking $7 million at the box office. At Loew’s State in New York it had rolled up $1.2 million, in Los Angeles crossed the million-dollar mark and close to that figure in Boston, Chicago, Philadelphia and San Francisco. Psycho was on the way to being one of the biggest grossers of the year.

With Hollywood still battling the encroaching threat of television, and television beginning to snare the first tranche of 1950s movies, it appeared that exhibitors had found a way of guaranteeing survival. But whether these new ideas would be sustained was another story.

SOURCES: Hy Hallinger, “1960 Reasoning: Teach Appreciation, Prepare Public for Single Feature European-Style Fixed Schedules,” Variety, Aug 3, 1960, p3; Brian Hannan, In Theaters Everywhere, A History of the Hollywood Wide Release 1913-2017 (McFarland, 2019), 117-134; “May Shift Main Feature Hour,” Variety, Aug 10, 1960, 13; “Gotham Playoff Revolution,” Variety, Aug 10, 1960, 13; “Re Broadway & Eastside Day-Dating,” Variety, Aug 10, 1960, 13; “Is a Queue Itself Best Form of Sell?,” Variety, Aug 10, 1960, 13.