Until the triumphant arrival of Oliver! (1968), the bar for British musicals was set very low. This just about scrapes through, thanks primarily to the enthusiastic cast and a rare opportunity to hear Sid James warble, though that may well be a detrimental factor.

At this point the British movie musical was kept aloft by pop stars, Cliff Richard (Summer Holiday, 1963) injecting box office life into a moribund mini-genre, The Beatles (A Hard Day’s Night, 1964) adding artistic credibility. Any pop star could front a musical, hence Ferry Across the Mersey (1965) starring Gerry and the Pacemakers, or if you filled the picture with enough stars (Gonks Go Beat, 1964) that was deemed sufficient.

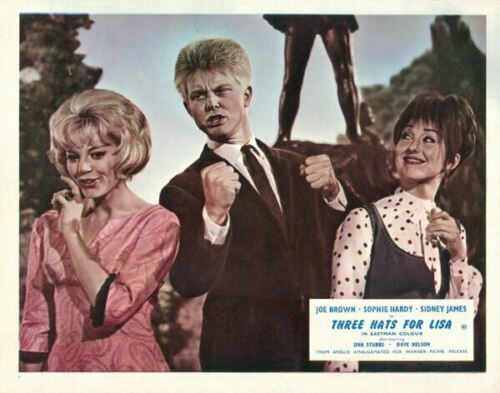

You would be hard put to place Joe Brown, leading man of Three Hats for Lisa, in the Cliff Richard/Beatles class and no British effort could come close to West Side Story (1961), Gigi (1958) or South Pacific (1958). Despite a paucity of hit singles – three Top Ten hits in 1962-1963 the extent of his chart success, Brown, voted UK Vocal Performer for 1962, and with a distinctive brush-cut, had already starred in What a Crazy World (1963), an adaptation of a stage musical, directed by Michael Carreras (The Lost Continent, 1968) which featured singers Susan Maugham, Marty Wilde and Freddie and the Dreamers.

But there was an emergent generation of stage songsmiths led by Lionel Bart (Oliver!, stage debut 1960) and Leslie Bricusse (Stop the World I Want To Get Off, stage debut 1961) and even the venerated John Barry (The Passion Flower Hotel, stage debut 1965) had tried his hand. Bricusse, on a publicity high after co-writing the lyrics for Goldfinger (1964), already had a movie musical to his name, Charley Moon (1956).

If Joe Brown had no proven box office cachet he was in good company. Frenchwoman Sophie Hardy had little musical experience that I’m aware of (unlike namesake Francoise Hardy), was making her English-speaking debut (as an Italian) and was best-known for Max Pecas’ number The Erotic Touch of Hot Skin (1964), a title that suggested far more than presumably the picture delivered. Una Stubbs, later famous for Till Death Us Do Part comedy series, was equally unknown.

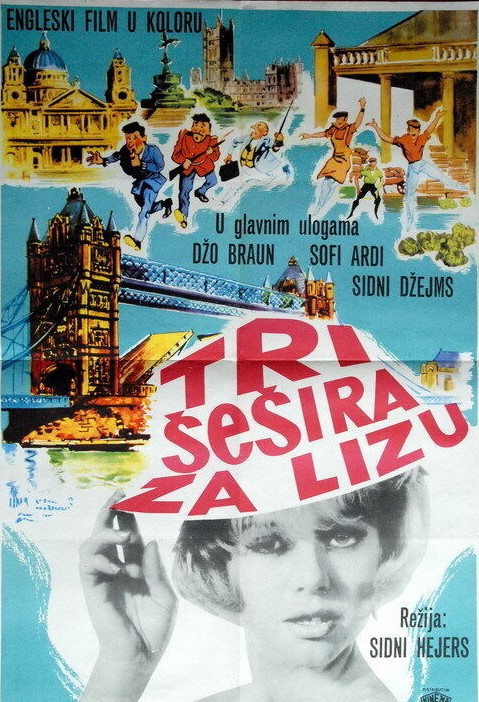

Narrative was the least consideration when crafting a British movie musical. This gets by on the notion that three irrepressible Cockneys – Johnny (Joe Brown), Flora (Una Stubbs) and Sammy (Dave Nelson) – somehow get entangled with a sexy Italian movie star Lisa (Sophie Hardy) who wants to dodge out of work commitments and collect a selection of typical British hats: a bowler, a busby (bearskin) and policeman headgear. Taxi driver Sid (Sidney James) is along, literally, for the ride. The rest of the time it’s a Swinging Sixties London travelog, an opening aerial shot of the capital, iconic sites to the fore, setting the scene, and subsequently cramming in as many tourist attractions as possible.

Every couple of minutes, for no particular reason, they burst into song and faux-West Side Story choreography. In fact, it’s stuffed with songs, fourteen over a short running time. Some are clearly spoofs – “The Boy on the Corner of the Street Where I Live” for example, or “Bermondsey” and none are particularly hummable. On the plus side, all the song-and-dance numbers are exteriors, though presumably because it was cheaper than hiring studio space. That London remained dry enough to accommodate such spectacles is probably the only miracle on show.

It’s far from dreary, and the story is daft enough, in the vein of 1940s Hollywood musicals, to get by, and the young cast fling themselves about quite splendidly, and there’s certainly an innocence to the proceedings, Johnny settling for just a kiss on the cheek from Lisa, and it would have probably stretched the imagination even more had serious romance beckoned. It seems a shame to mark down such effervescence, and though it’s in reality a two out of five, it’s not in the execrable league so I’m giving it the benefit of the doubt especially as it was directed by Sidney Hayers (Night of the Eagle/Burn, Witch, Burn, 1962) who usually manages to salvage something from unprepossessing material. And also because neither Sid James nor Talbot Rothwell, the Carry On series resident writer, give in to the temptation of the double entendre.