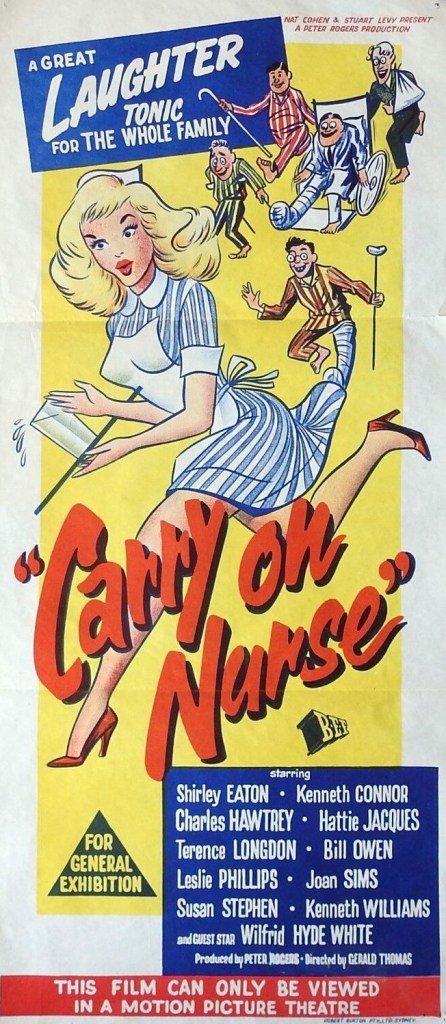

There was no greater divide between audiences and critics in Britain than the long-running comedy “Carry On” series (outside of an occasional satirical bulls-eye like Carry On Up the Khyber, 1968). And a similar gulf existed between the type of audiences the movies attracted in Britain and those in America. In Britain they were vastly popular general releases while in America their usual habitat was the arthouse as if they were seen as the natural successors to the Ealing comedies. And there was a third chasm – between the endearing risqué early comedies and the more lascivious later versions.

Carry On Nurse fell into the endearing camp. The humor was gentle rather than forced, the emphasis on misunderstanding and innuendo and smooth seducers like Leslie Phillips rather than exposed female flesh and the grasping likes of the ever-chortling Sid James. Perhaps you could define this earlier film as pre-nasal Kenneth Williams, his peculiar type of delivery not yet at full throttle. Here there is innocence rather than lust and the males quake in fear not just of the indomitable Hattie Jacques in brusque matron mode but of the other efficient nurses led by Shirley Eaton who have the measure of their rather hapless patients, although student nurse Joan Sims – making her series debut – is an accident-prone soul.

The action is mostly confined to a male ward. There are plenty of gags – alarms rung by mistake, boiling catheters burned to a turn, medication making a patient go wild, patients intoxicated by laughing gas and the famous replacement of a rectal thermometer by a daffodil. Wilfred Hyde-White as a constant complainer and obsessive radio listener Charles Hawtrey provide further ongoing amusement.

But the thrust of the story is romance. Journalist Terence Longdon fancies Shirley Eaton but his initial advances are spurned as she is in love with a doctor. In a role far removed from his later brazen characters, Williams plays a shy intellectual who finally comes round to the charms of Jill Ireland (later wife of Charles Bronson). Although Leslie Phillips is his usual suave self, he makes no designs on the female staff since he has a girlfriend elsewhere and his ailment – a bunion on the bum – makes him an unlikely candidate for a hospital liaison.

Hattie Jacques is in imperious form, Shirley Eaton shows what she is capable of, Kenneth Williams playing against type is a revelation.

British critics hated the “Carry On” films until late in the decade when Carry On Up the Khyber (1968) hit a satirical note. Critics felt the movies pandered to the lowest common denominator and were a poor substitute for the Ealing comedies which had given Britain an unexpected appreciation among American comedy fans.

It was a well-known fact the comedies did not always travel. Apart from Jacques Tati, the more vulgar French comedies featuring the likes of Fernandel were seen as arthouse fare. Unless they featured a sex angle or the promise of nudity, coarse Italians comedies struggled to find an international audience. The “Carry On” films were bawdy by inclination without being visually offensive

Carry On Sergeant (1958), the first in the series, had been a massive success in Britain. Distributor Anglo-Amalgamated was so convinced it would find a similar response in the U.S. that it was opened in New York at a first run arthouse. Although comedies were hardly standard arthouse fare, this was generally the route for low-budget British films. The picture lasted only three weeks and taking that as proof of its dismal prospects other exhibitors ignored it.

The follow-up Carry On Nurse (1959) took an entirely different route when launched in America in 1960. This time New York would be virtually the last leg of its exhibition tour. Instead it opened on March 10 at the 750-seat Crest in Los Angeles. Away from the New York spotlight, the little movie attracted not just good notices but decent audiences.

Instead of being whipped off screens after a few weeks, it developed legs. In Chicago it ran for 16 weeks in first run before transferring to a further 50 theaters. Within a few months of opening it had been released in 48 cities. In Minneapolis it was booked as a “filler” at the World arthouse, expected to run a week and no more. Instead, it remained for six weeks and when it shifted out to the nabes out-grossed Billy Wilder’s big-budget comedy The Apartment (1960) with a stellar cast of Jack Lemmon and Shirley Maclaine.

In its fourth month at the 600-seat Fox Esquire in Denver where it opened in May, it set a new long-run record for a non-roadshow picture. It had been taking in a steady $4,000 a week since opening.

SOURCES: “How To Nurse a Foreign Pic That’s Neither Art nor Nudie: Skip N.Y.,” Variety, Aug 24, 1960, 3; “British Carry On Nurse A Sleeper in Mpls With Long Lopp Run, Nabe Biz,” Variety, Aug 24, 1960, 18;

Note: by and large this blog follows American release dates so although Carry On Nurse was shown in Britain in 1959 it did not reach America until 1960.