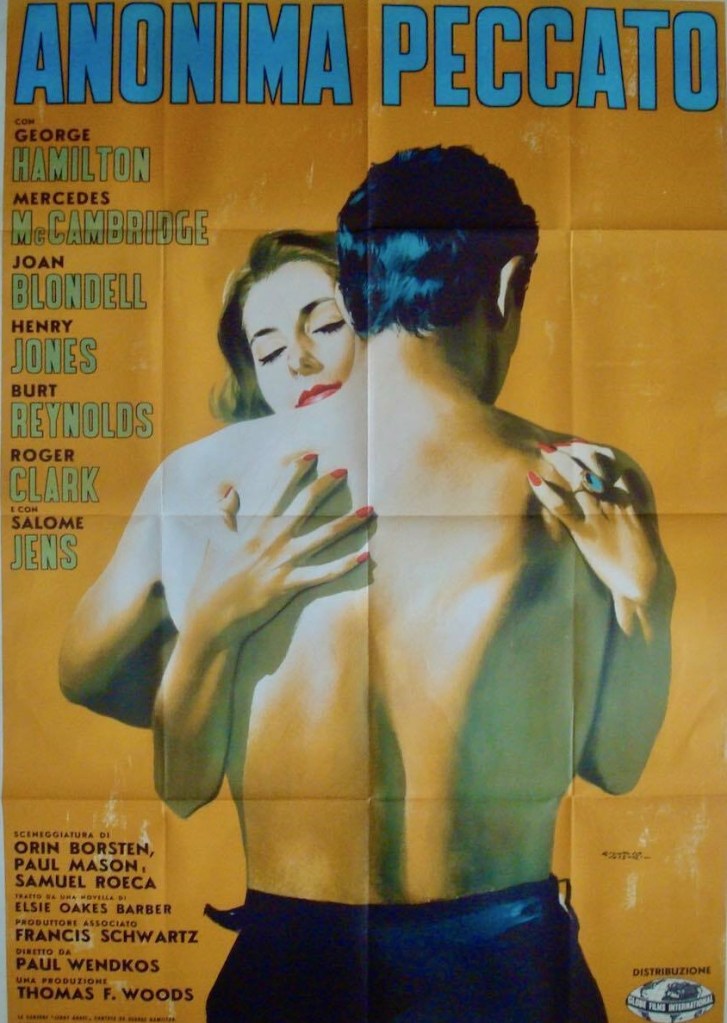

Stunning cast – George Hamilton, Burt Reynolds, Mercedes McCambridge, Joan Blondell – in low-rent version of that ode to evangelism Elmer Gantry (1960) but here focusing on misplaced zeal and corruptible innocence. Strikes a contemporary note with “MeToo” reversal – elder woman grooming a choir boy – and fake news, how else to describe public gullibility for the so-called miracles that were the stock-in-trade of the revivalist business.

Would have been an interesting addition to the portfolio of the erratic director Hubert Cornfield (Pressure Point, 1962 a high, but Night of the Following Day, 1969, a low) except he took ill and passed the reins to Paul Wendkos (Guns of The Magnificent Seven, 1969).

Takes an interesting narrative slant, the three original principals bowing out after a strong start, leaving the way free for the titular character to come unstuck in the sleazy world of religious make-believe before they all turn up again for a rip-roaring finale.

Young charismatic preacher Paul (George Hamilton) is at odds with his dominating older wife Sarah (Mercedes McCambridge). She is all hellfire-and-brimstone while he wants to preach about love. They are in an “unholy marriage,” he plucked from the choir as a teenager and molded by her, her invocations to prayer always accompanied by sex, and once Jenny Angel (Salome Jens), a mute he heals and with an unwelcome boyfriend Hoke (Burt Reynolds), appears on the scene he begins to question his sexual and religious grooming.

Recognizing a love rival, Sarah bribes ambitious couple, resident alcoholics Mollie (Joan Blondell) and Ben (Henry Jones), to take her on and they, in turn, trade her to Sam (Roger Clark) who turns her unfulfilled potential as a preacher into box office dynamite by capitalizing first on her beauty, low-cut gowns emphasizing her physical attributes, and then by fake healings, not realizing, in his greed, that a preacher who can make reputedly make the blind see is asking for trouble.

Having seen the error of his way, Paul chases after Angel, Sarah chases after Paul and Hoke just happens to be in vicinity to ensure it all ends in colossal disaster, though with an unusual twist ending.

But it’s surprisingly good in an old-fashioned way. The depiction of the corrupt evangelists and, more importantly, the spiritual and actual poverty of the congregations, desperately looking for salvation, occasionally blaming God for their woes, and hoping sheer blind faith will see them through, is well done, even if Paul’s preaching sails close to the unsavory, with rather lewd accompaniments.

Jenny’s conviction in the face of initial failure that she can bring solace to the people is also believable. All innocence, no idea she is being duped, she simply perseveres, undaunted at the scale of her task, faced with dozens of critically-ill expecting cure.

Sam’s real scam is selling some kind of miracle potion that Jenny has apparently endorsed, the phone ringing off the hook with customers wishing to buy it once the preacher’s fame spreads. He, too, despite apparently God-fearing ways, is partial to liquor.

Given Jenny never doubts her vocation, you’d expect an innocence-sized hole at the center of the drama, but that’s filled up by the growing conflict between Paul and Sarah and a very humorous section dealing with the idiotic Mollie and Ben, especially in an inspired drunken scene.

It could easily have been a more cynical take on the dumb audience, so easily taken in, but instead, they are presented as individuals at the end of their tether with nowhere else to go but the Almighty in the hope that the burden of living terrible lives will be eased. How easily they are manipulated is no surprise.

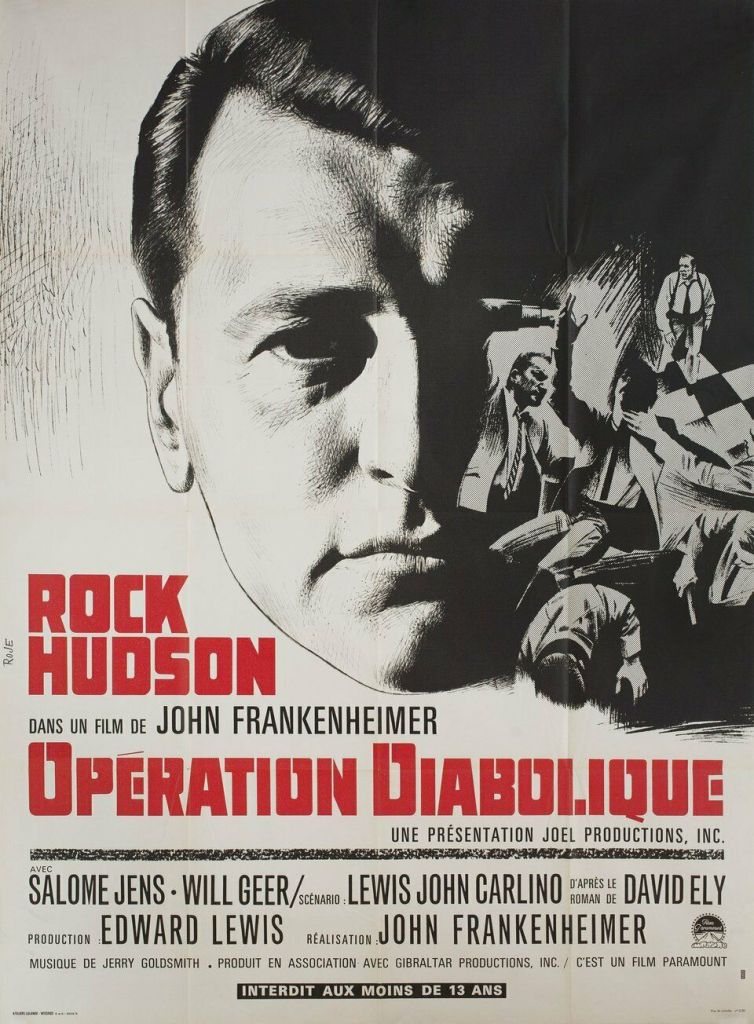

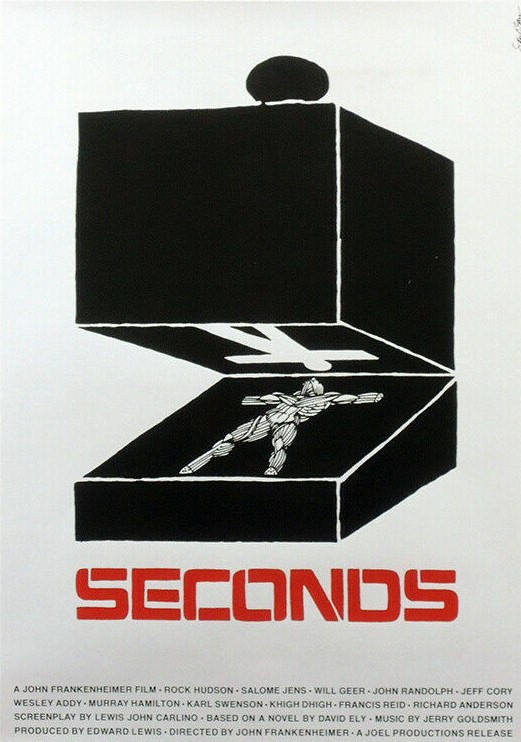

George Hamilton (A Time for Killing, 1967) is unrecognizable, not just in the acting which at times has the charming creepiness of Anthony Perkins, but because, since this is made in black-and-white, he is devoid of his usual inches-thick tan. I was reminded a lot of Carrie (1976) in that Piper Laurie’s portrayal of the obsessed mother appeared modelled on that of Mercedes McCambridge (99 Women, 1969) as the scary wife and in Sissy Spacek’s imperturbability as she strides through the chaos she has caused that was a throwback to the gait of Salome Jens (Seconds, 1966) as she walks unharmed away from the wreck of her work.

Except for her physical presence, Jens isn’t given sufficient contemplation to make her stand out, and to some extent is just an object of other people’s satisfaction, but is at her best when clearly puzzled that, believing herself touched by God, her initial ministry fails to take off.

Burt Reynolds (Fade In, 1968) makes the kind of debut that would have gone unnoticed had he not a decade later transmogrified into a superstar. Hollywood Golden Age star Joan Blondell (Model Wife, 1941) has a sparkling turn as the blowsy alcoholic who invents Jenny’s stage name of Angel Baby.

Paul Wendkos makes the whole thing work by concentrating on two-character scenes, limited movement creating intensity, that works equally well for conflict and humor, while deftly managing the crowd scenes and pulling off the unexpected ending. Took considerable effort to knock Elsie Oakes Barber’s novel into shape, three screenwriters, neophytes in the main, involved – Orin Borstein in his debut and only screenplay, Paul Mason, no other screenplay credit until The Ladies Club (1986) and Samuel Roeca (Fluffy, 1965).

An interesting watch, not just for the cast, but as a reminder that it’s never too difficult to dupe a willing audience.