Little gem with a terrific central performance. We tend to be condescending to these old British crime B-features. Occasionally one achieves cult status but mostly critics these days are as dismissive as back in the day. You might be surprised to learn that audiences treated them with a good deal more respect. In making up the support on a double bill, they represented value for money.

It’s also easy to forget that at this point the public were not inundated with television detectives and the true-crime genre had not been invented. Tales like this one, while lacking a big budget, proved very satisfactory viewing, especially if they were as clever as this. I could see the plot of Smokescreen being easily remade for a television one-off or as part of a series.

Main character, insurance agent rather than police detective, in his personal awkward demeanor, reminds me a great deal of the current BBC hit Ludwig.

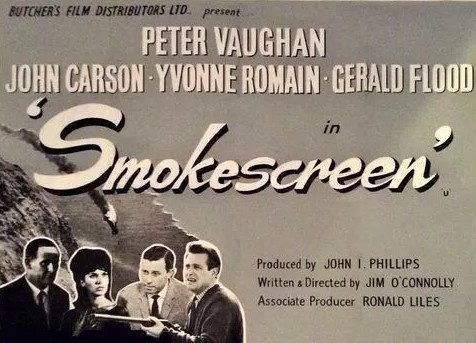

Significant effort has gone into developing Roper (Peter Vaughan). For someone meant to be upholding the law, he skirts the rules in the matter of his personal expenses, ensuring he always finds the correct price for a taxi or a hotel meal before doing without and claiming it. So he doesn’t at all come across as an attractive character. He looks sly, sleekit, and he’s not smart enough to know how to butter up the office secretary Miss Breen (Barbara Hicks), who always wants minor attention, a postcard or similar.

Like Charles like Nothing but the Best (1964), he’s a sponger, without that character’s class or charm. Sent out on a case to Brighton on England’s south coast, hoping to find a missing man still alive and his wife making a false claim, he ensures that a professional colleague Carson (Trevor Bayliss) does all the driving, saving Roper on taxi fares which he can illicitly claim back. There’s an excuse for this unattractive behavior, but I preferred him less obviously redeemed.

Anyway, he’s a joy to watch, a real person with ordinary flaws rather than the usual ones afflicted contemporary detectives such as alcohol or drug abuse or failing marriage or an affair or requiring serious redemption for past major error.

All the characters have been well fleshed out. Carson nurtures secret feelings for supposed widow Janet (Yvonne Romaine). But she doesn’t at all come across as a femme fatale, which goes against the actress’s screen persona. There’s a great scene with a doctor (Derek Francis) whom his colleague upsets – Roper tiptoes away from the trouble – and who then demands a fee for being professionally consulted even if it’s only a few minutes in his garden.

Local cop Insp Wright (Glynn Edwards) is similarly offhand and down-to-earth, there’s a nice piece of comedy with a station master (Derek Guyler) and a great scene where Roper is way out of his element – and his league – trying to pump information out of a very attractive secretary (Penny Morrell) by getting her drunk, and wincing every time she puts an expensive cocktail on the bill.

Roper’s diligence pays off in the end, but there’s no grandstanding, as there is with Ludwig or any other cop, when he solves the case.

It’s a very clever story well told, enough interest to keep an audience feeling it has been entertained and if the main feature comes up to scratch back in the day would come out of the cinema very satisfied indeed. Roper manages proper detection, miffed when said colleague is correct in an assumption Roper dismissed, and the diligence that requires.

With little of a budget to speak of, these B-features had to make up for the lack of expensive location shots or camera tricks by ensuring the script not just ticked along nicely and provided an interesting resolution but that the characters appeared real, making up for lacking the cosmetic of attractiveness by reminding an audience of real people. Everyone would know a penny-pincher like Roper’s boss or a snippy secretary who can bring employees to heel or a sleekit colleague who’s doing a minor bit of ducking and diving.

This is a particularly significant turn by Peter Vaughan – who you might remember as the elderly Maester in Game of Thrones – because he made his name playing villains generally lacking any nuance. He was the titular evil criminal mastermind in Hammerhead (1968), a thug in Twist of Sand (1968), a nasty piece of work in Straw Dogs (1971). Although he found regular work as a character actor, he might find it somewhat disappointing that he was never again let near anything quite as finished as this piece. Yvonne Romain (Return to Sender, 1963) toys with her screen persona. Future British television dependables pop up everywhere, Gerald Flood and Sam Kydd in addition to Glynn Edwards and Deryck Guyler

Writer-director Jim O’Connolly (The Valley of Gwangi) writes some great stuff and is lucky to have the actors who can pull it off.

Great characters, solid detection and excellent twists.