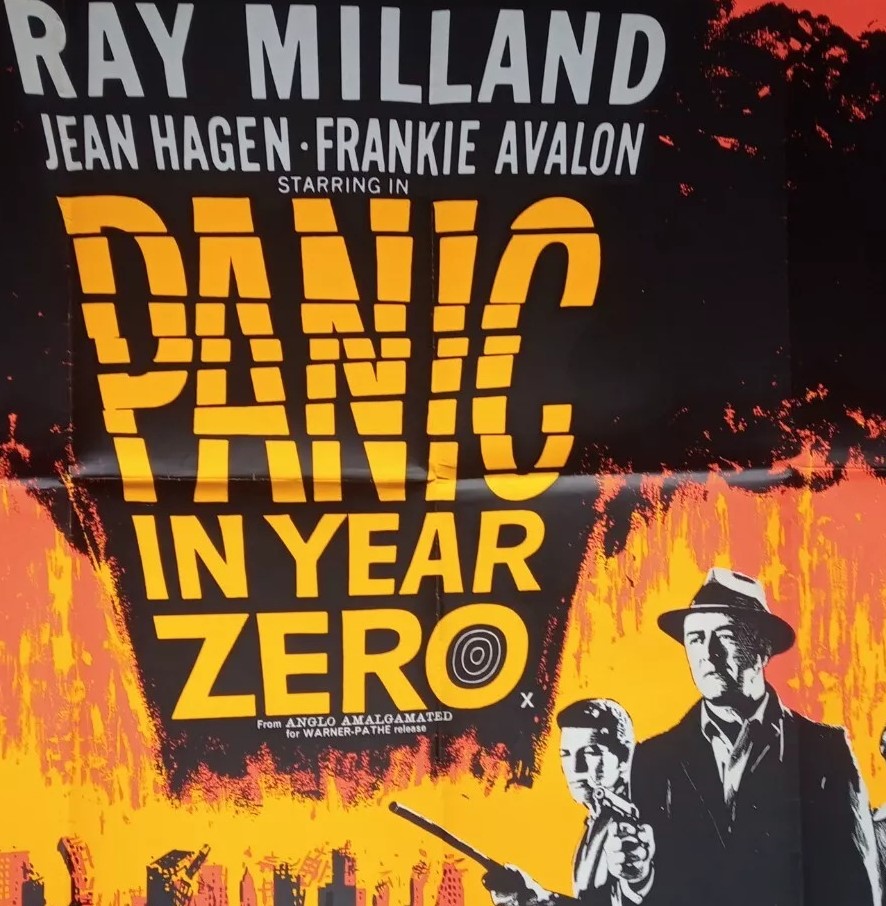

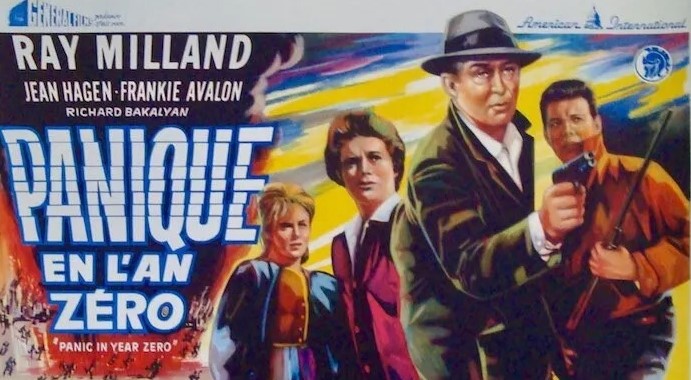

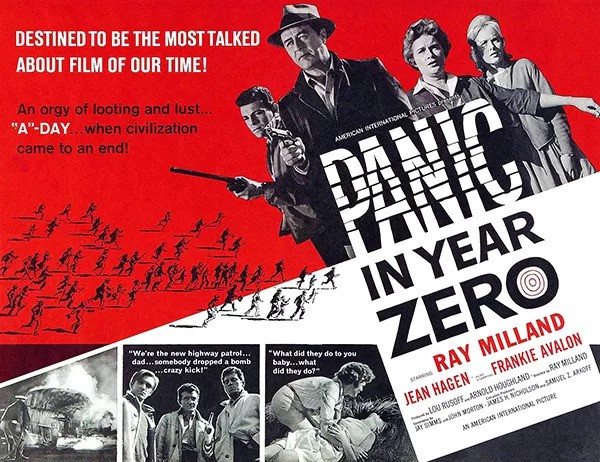

While the release of Conclave and Juror #2 augurs well for the future of movies made for the more mature audience, it’s worth remembering that such fare was commonplace six decades ago, even in the lower-budget strata. Well-structured, well-acted drama was never hard to find. Since I stack my DVDs on their sides and make my selection based on the title on the spine, I rarely glance at cover art, and just as well here, because the poster, I realized, in the process of selling the movie, gave away too much.

Beyond a vague notion that it concerned the aftermath of a nuclear holocaust I had no idea whether this would lean towards the dystopian or the survivalist. And there’s little clue at the start. We open on a typical suburban family holiday scene – husband Harry (Ray Milland) flexing his fishing rod, wife Ann (Jean Hagen) complaining of being overburdened with the loading of the trailer, teenage daughter Karen (Mary Mitchell) and son Rick (Frankie Avalon) moaning about being dragged out of their beds at an unearthly hour.

Not long into the journey they see flashes in the distance and a mushroom cloud above Los Angeles. Harry is alerted to potential danger when he observes a pump attendant being slugged by a driver over four bucks’ worth of fuel. Harry’s clearly the reserved kind of businessman, happily married, still flirting with a wife who giggles at such overt attention. But when the roads are filled with cars speeding away from the disaster area and the radio clams up and telephone lines are down, Harry’s personality undergoes a dramatic change, much to the disgust of his wife.

If this had been made these days, it would focus on the kids as they came to terms with post-apocalyptic catastrophe and some militaristic domineering governing body getting in their way or trying to control them. Or it would be some musclebound jerk only too ready to battle his way out of trouble.

Instead we have a gentleman tugging on his inner tough guy. Harry knocks around a storekeeper (Richard Garland), gets the better of a trio of thugs, charges through a roadblock, carves a route through a busy roadway by setting fire to it, destroys a bridge on a rural road to prevent being followed, and is capable of shooting anyone threatening his family. He’s not gone rogue, though, careful to keep more trigger-happy son in line, warning against civilization going to ruin.

This is so well-constructed you don’t know what’s going to happen next, nor, despite ample warning, to discover that Harry is quite the adaptable survivalist, not just stocking up on supplies, but dumping the trailer in favor of holing up in a remote cave, not quite going back to nature given the quantity of provisions to hand. But, yes, they do wash clothes in a stream, cook on a camping stove, shoot game and sleep in uncomfortable beds.

It’s not an idyll because the storekeeper and the three thugs have chosen the same locale. The hoodlums murder the storekeep’s family, kidnap young women including Marilyn (Joan Freeman) and are always on the prowl for easy pickings, which includes Karen, triggering a climactic shoot-out.

Despite the poster promising orgies of various kinds, there’s no glorifying the violence, Harry more like the frontiersman or law-abiding citizen forced to take the law into his own hands. Ann, whose maternal instinct has focused on its gentler aspects, turns into a lioness defending her cubs. It’s a brutal awakening for all, except Rick who appears to thoroughly enjoy the experience even as his father is trying to steer him clear of such thoughts.

Made by American International on a minimal budget, Ray Milland, doubling up as director, shows just what you can do with a decent script and cunning choice of locale. British-born Milland, a big star for Paramount in the 1930s-1940s and Oscar-winner to boot for The Lost Weekend (1945), read the runes right for the following decade and excepting Hitchcock’s Dial M for Murder (1954) and realizing his marquee value had tumbled, took to direction, beginning with A Man Alone (1955) and Lisbon (1956). He was top-billed in both, joined by Maureen O’Hara (The Rare Breed, 1966) for the second.

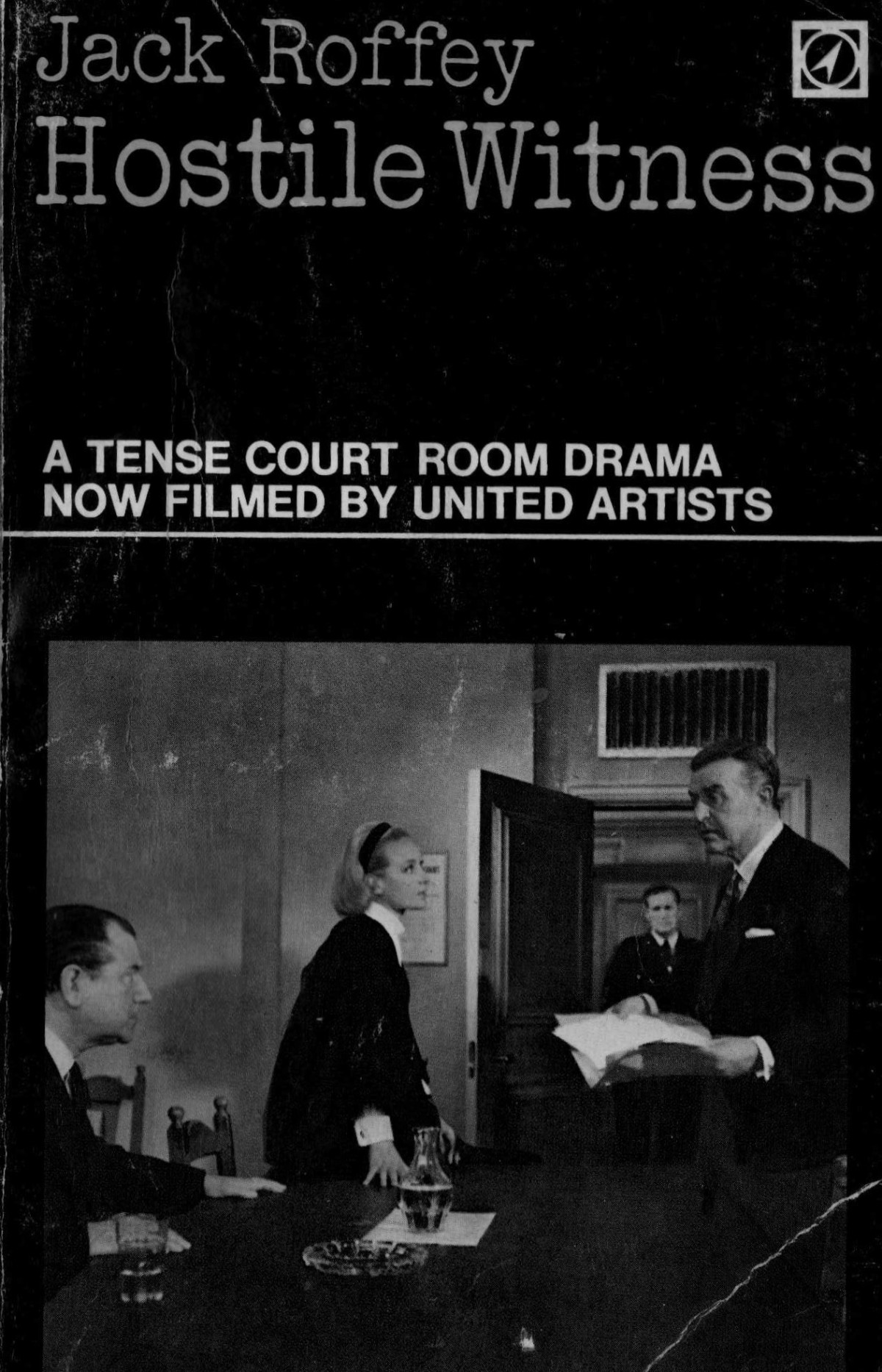

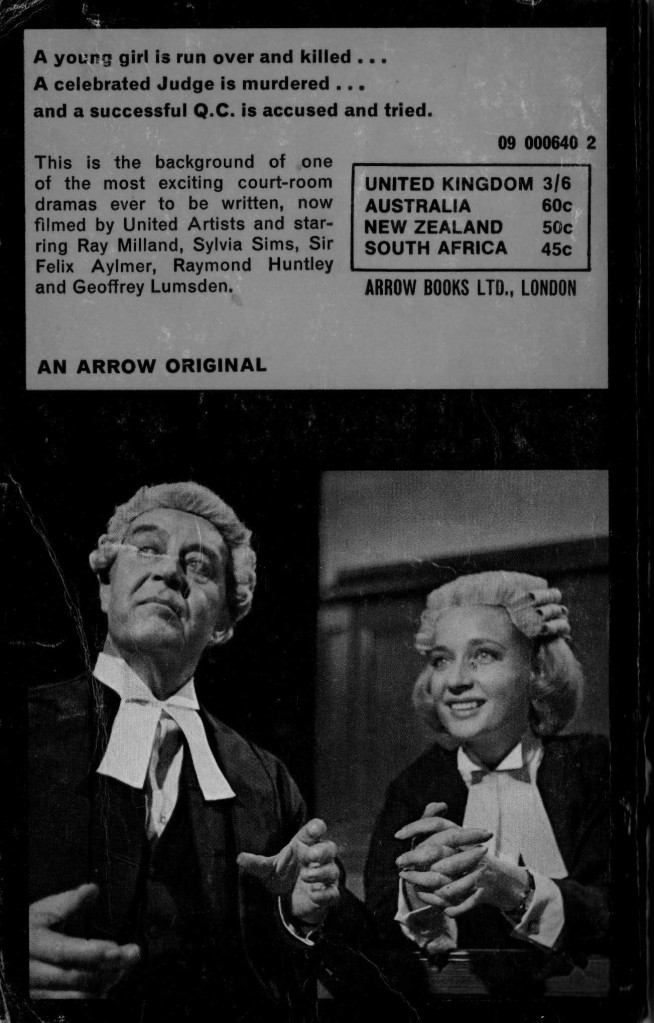

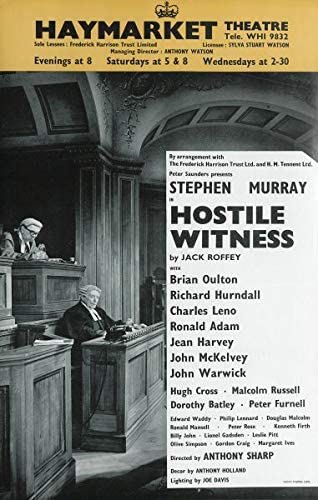

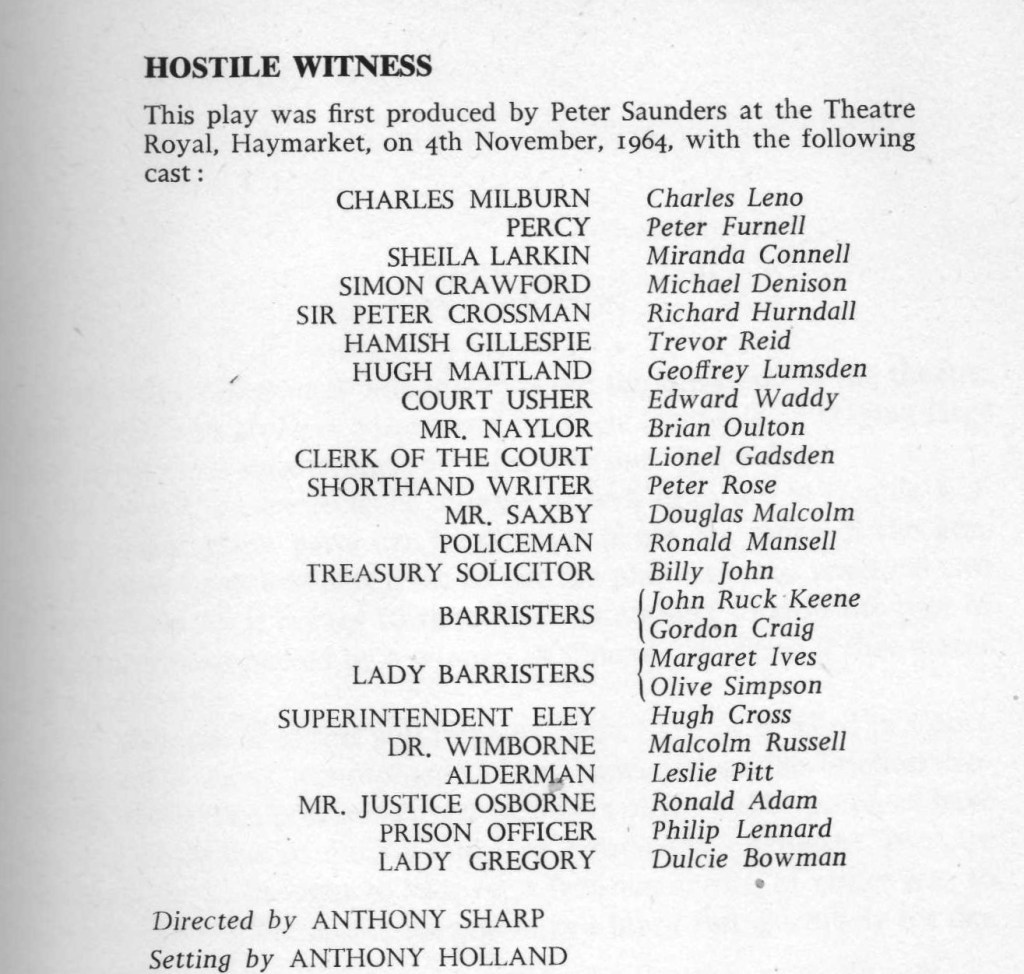

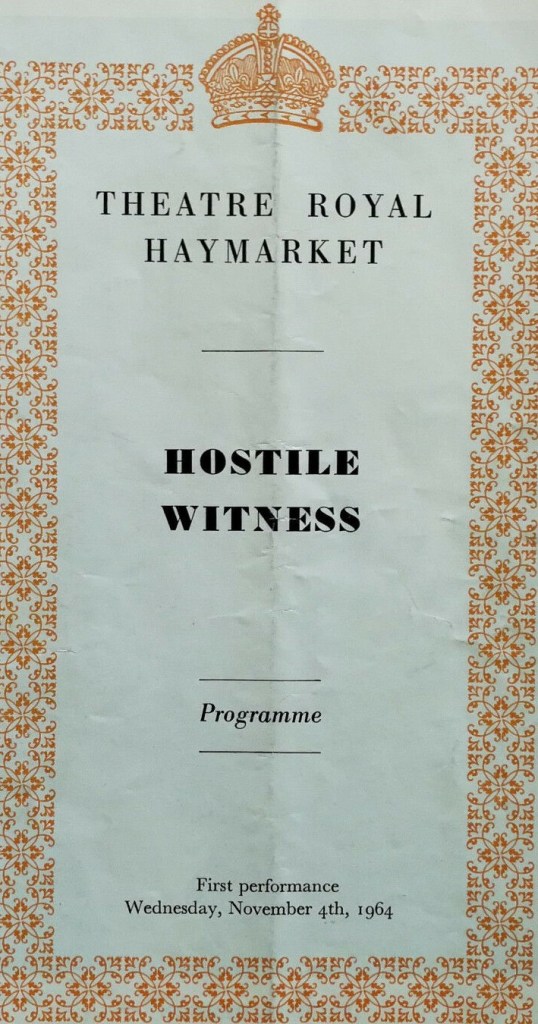

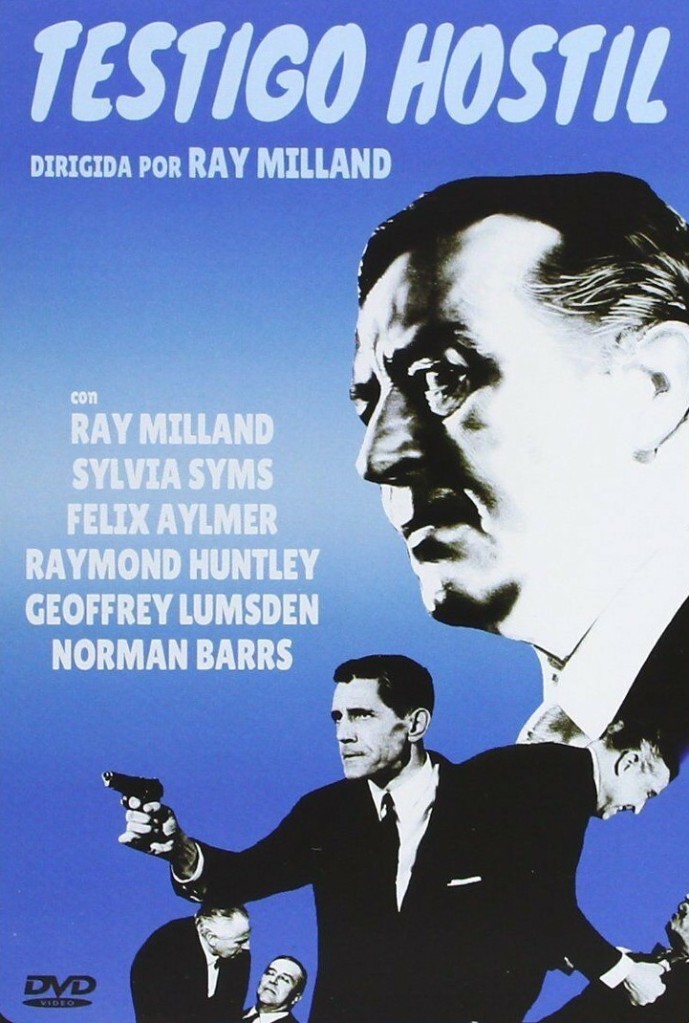

His last stab at direction was Hostile Witness (1968). But he only helmed five movies in all. While you wouldn’t say he was a natural stylist, Panic in the Year Zero! is something of a triumph, keeping audiences on edge with both narrative and character-led twists.

Apocalypse wasn’t even a sub-genre at this point, Eve (1951) the only previous example of any note. Timing didn’t help this picture, the Cuban Missile Crisis occurring a few months after its initial release.

Milland makes the most of his gritty characterization, pop star Frankie Avalon (The Million Eyes of Sumuru, 1967) surprisingly good. Written by Jay Simms (Creation of the Humanoids, 1962) and John Morton, in his debut, from source material by Ward Moore.

Rewarding.