A three-hour western epic directed by Stanley Kubrick (2001: A Space Odyssey, 1968), written by Sam Peckinpah (The Wild Bunch, 1969) and The Twilight Zone’s Rod Serling and starring Spencer Tracy (Judgement at Nuremberg, 1961) and Marlon Brando. What’s not to like? That all of these major players, with the exception of Brando, had nothing to do with the final product was par for the course for a movie that didn’t reach cinema screens until two years after shooting was completed.

Marlon Brando was riding high when the project was first mooted in 1956. The box office and critical sensation of the 1950s, four Oscar nominations in successive years, winner for On the Waterfront (1954), his price was rising by the minute. And he had ambitions to take control of his career, set up his own production shingle, a trend that was beginning to gather pace.

He established Pennebaker (named after his mother) Productions in 1957 with ex-marketeer Walter Seltzer, producer of 711 Ocean Drive (1950), and George Glass, a former partner in Stanley Kramer’s independent production company. Paramount agreed to back the company. A western, A Burst of Vermilion, was intended as the company’s first offering. Soon there were five movies on the schedule including The Authentic Death of Hendry Jones by Charles Neider.

Brando had paid $150,000 for the rights to the book and a script by Sam Peckinpah. The original title was changed to Guns Up. It was going to mark the debut of the new Pennebaker outfit ahead of other projected movies like Shake Hands with the Devil to star James Cagney and Anthony Perkins (he didn’t make it to the final cast), The Raging Man and Ride, Comancheros (no relation to The Comancheros, 1961) and C’Est La Vie to be filmed in Paris.

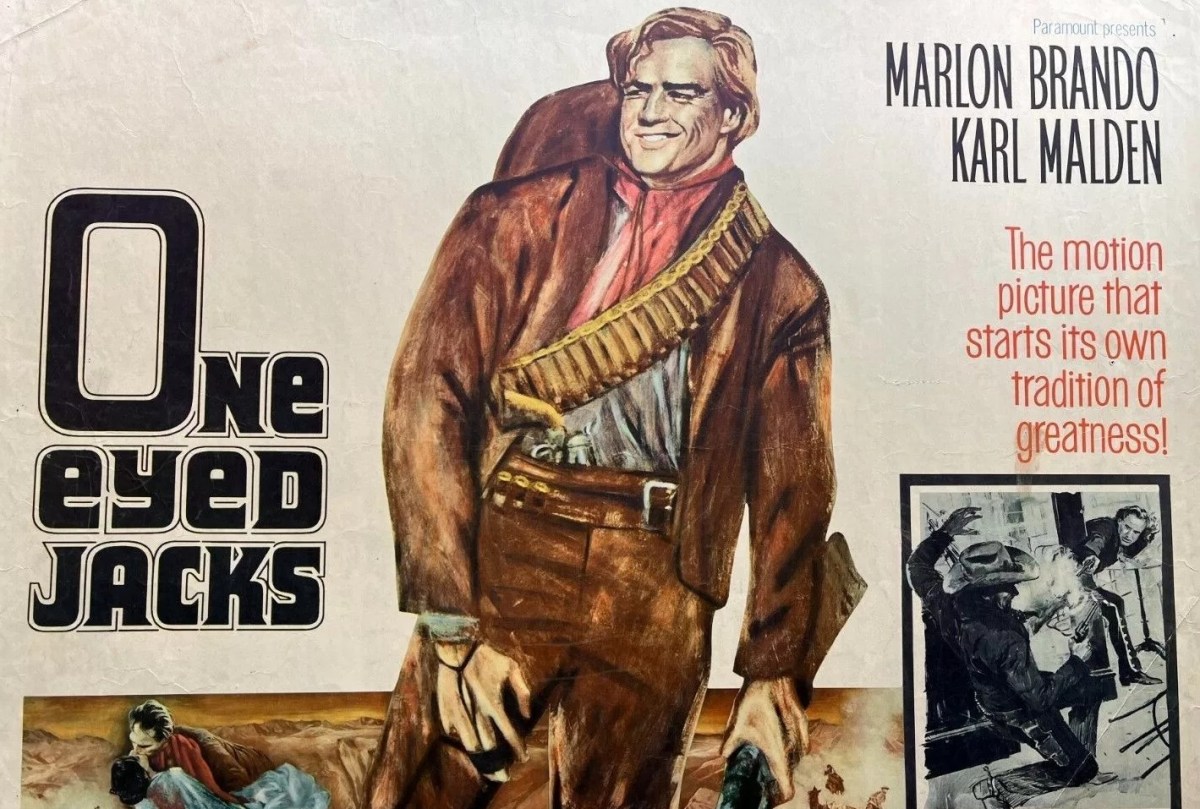

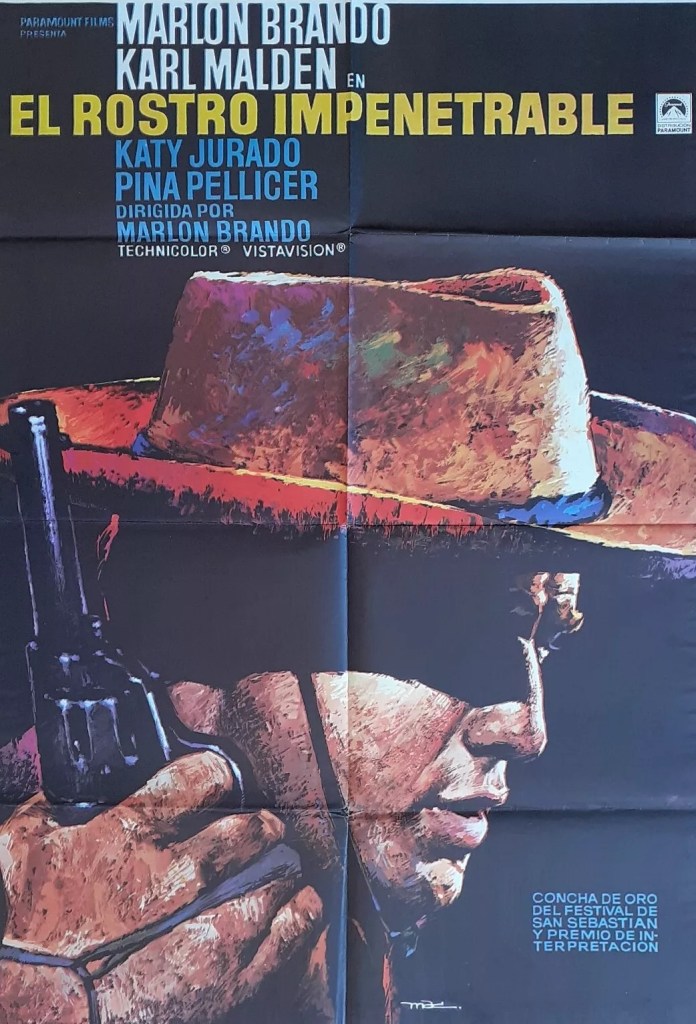

Paramount paid through the nose, committing to an unprecedented deal. The studio would fund the entire cost of Guns Up and as well as $150,000 upfront Brando would receive 100 per cent of the profits, Paramount relying on its 27% of the gross as a distribution fee to turn a profit. Stanley Kubrick, riding high after Paths of Glory (1957), was hired to direct. While the studio preferred Spencer Tracy as co-star, Brando wanted old buddy Karl Malden who had co-starred with Brando in A Streetcar Named Desire (1951) and On the Waterfront, winning an Oscar for the former and a nomination for the latter.

And in part to reflect the Asian community in Monterey, location of the main section of the film, he also wanted current squeeze France Nuyen (A Girl Named Tamiko, 1962) to play his lover in the film, but Kubrick was aghast and instead cast Mexican debutante Pina Pellicer (Rogelia, 1962). There were roles for Katy Jurado (Barabbas, 1962) and recognizable western types like Ben Johnson (The Undefeated, 1969), Slim Pickens (Firecreek, 1968) and Elisha Cook Jr (The Great Bank Robbery, 1969).

Shooting was set for June 1958, then it shifted to September and then November. To Brando’s shock, Kubrick pulled out two weeks before production was due to begin, citing pre-production on Lolita (which, ironically, didn’t go ahead for a couple of years). To salvage the situation, Brando decided to direct. He wasn’t the first actor to go down this route, especially if you count Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton and Orson Welles as actors first and foremost. Laurence Olivier helmed Henry V (1944) and three others, Jose Ferrer The Cockleshell Heroes (1955), hoofer Gene Kelly Singin’ in the Rain (1951) and Charles Laughton Night of the Hunter, 1955. So he was in good company.

Cameras turned on December 2, 1958. It was an auspicious era for westerns, a total of 41 had appeared that year. Although budgeted for three months, it took six months to shoot in locations like Sonora in Mexico and Monterey in California (where the film was set) as well as Pfeiffer Beach on the Big Sur and the Warner Ranch.

Although prior to shooting commencing the title had changed to One-Eyed Jacks, scoring and editing were well in hand and Paramount announced it as one of its 17 pictures set for 1959 release. In the end Shake Hands with the Devil beat it to the punch as Pennebaker’s initial release, in 1959. But it didn’t favor so well, skipping the more lucrative but riskier Broadway first run in favour of hitting the circuits.

Meanwhile, Brando was angling for a three-hour running time. The budget kept increasing. The original $2m budget had doubled. Eventually, Paramount acknowledged it had cost $5 million though other estimates put it closer to $6 million.

Part of the problem in readying it for release was Brando’s other commitments. He was still a working actor and could hardly resist the offer of a record-setting one million bucks to star in The Fugitive Kind (1960). Even so, the bigger problem was not time, but experience and a first-time director being unable to make up his mind, having shot a colossal amount of footage and having tremendous difficulty trimming it down to workable length. Paramount still had it on the release agenda in 1960. It was going to be a “special release,” which most people took, especially given the running time, to be roadshow.

But by December 1960, the studio had waited long enough and just before Xmas the studio took over the editing and after editing out around 40 minutes from Brando’s three hour cut, Paramount scheduled it for a world premiere in New York in March 20, 1961, in a kind of semi-roadshow – moviegoers could buy in advance but the tickets did not come with reserved seats, which was the whole point of roadshow. Nor were prices hiked, which was gave roadshow its prestige.

Already deemed “Brando’s Folly” and coming in the wake of The Alamo (1960), the John Wayne-directed epic which had flopped in roadshow, commercial hopes were not high. In part, because production had been so long ago it had skipped under the journalistic radar which was concentrating on skewering The Alamo and the equally troubled The Misfits (1961). So it didn’t come trailing disaster. Still, it seemed more likely, audiences would not take to the odd tale which didn’t fit so easily into the western genre. Plus Brando’s previous effort The Fugitive Kind had been his first outright flop.

Turned out, though, Brando still was a major attraction. It snaffled a “huge” $81,000 in its opener at the 4,820-seat Capitol in New York. There was a “smasheroo” $21,000 in Detroit, a “big” $14,000 in Buffalo, a “hotsy” $15,000 in Cincinnati. “Giant” was the preferred adjective, covering $60,000 in Chicago, $32,000 in Philadelphia and $15,000 in Boston.

Rentals (what studios make after cinemas have taken their share of the gross) amounted to a very decent $4.3 million, enough to rank seventeenth for the year. And whereas those figures were considered decent enough, it did “substantially better abroad.”

So, more than likely, against all the self-destructive odds, it earned a profit.

SOURCES: Stefan Kanfer, Somebody, The Reckless Life and Remarkable Career of Marlon Brando (Faber & Faber, 2008); “Glass, Seltzer in Brando Co Berths,” Variety, April 17, 1957, p22; “Chatter, Hollywood,” Variety, May 22, 1957, p62; “Marlon Brando Guns Up for Paramount,” Variety, April 30, 1958, p22; “Chatter, Paris,” Variety, July 30, 1958, p126; “Brando Gets 100% of Film Profit!”, Variety, August 6, 1958, p1; “Briefs from Lots,” Variety, September 24, 1958, p15; “Marlon Brando’s Own,” Variety, November 26, 1958, p5; “Shake Hands First with Circuits,” Variety, May 6, 1959, p4; “Brando’s Ugly American,” Variety, July 1, 1959, p3; “Par 17 Pix Set for Release,” Variety, July 15, 1959, p5; “Par Division Eyes Upcoming Product,” Variety, November 25, 1959, p22; “Doubt or Delay re Brando’s Jacks,” Variety, August 10, 1960, p3; “Brando Jacks Editing,” Variety, December 21, 1960, p7; Advert, Variety, January 6, 1960, p32; Box Office Figures, Variety, April 5-Jul 24, 1961; “Hoss Operas in O’Seas Gallop,” Variety, August 23, 1961, p16; “1961 Rentals and Potential,” Variety, January 10, 1962, p13.