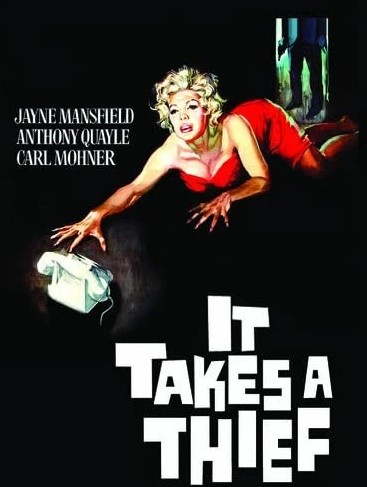

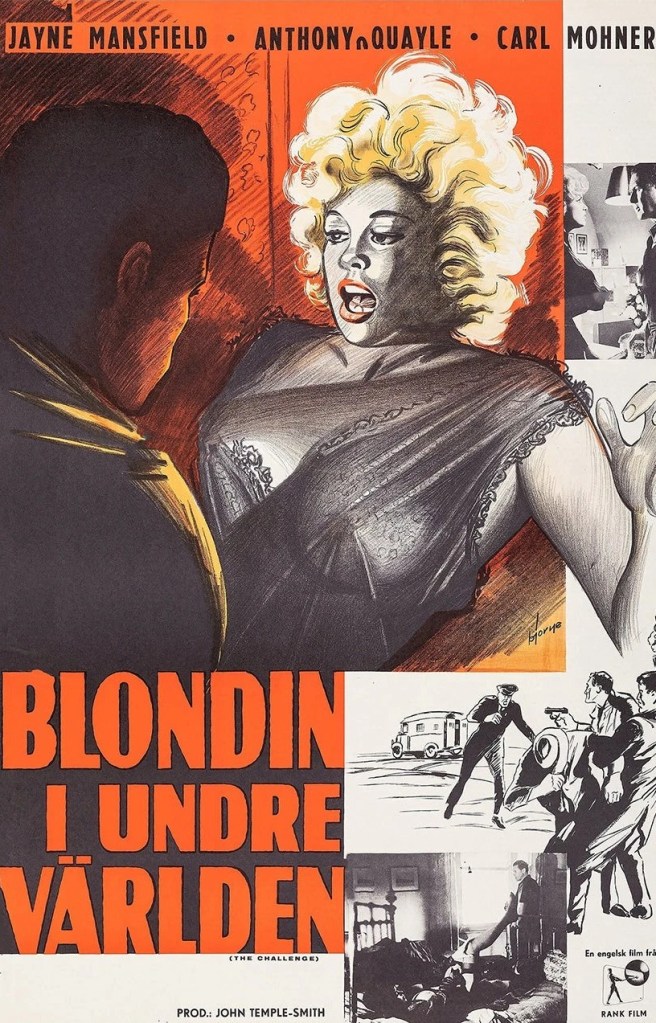

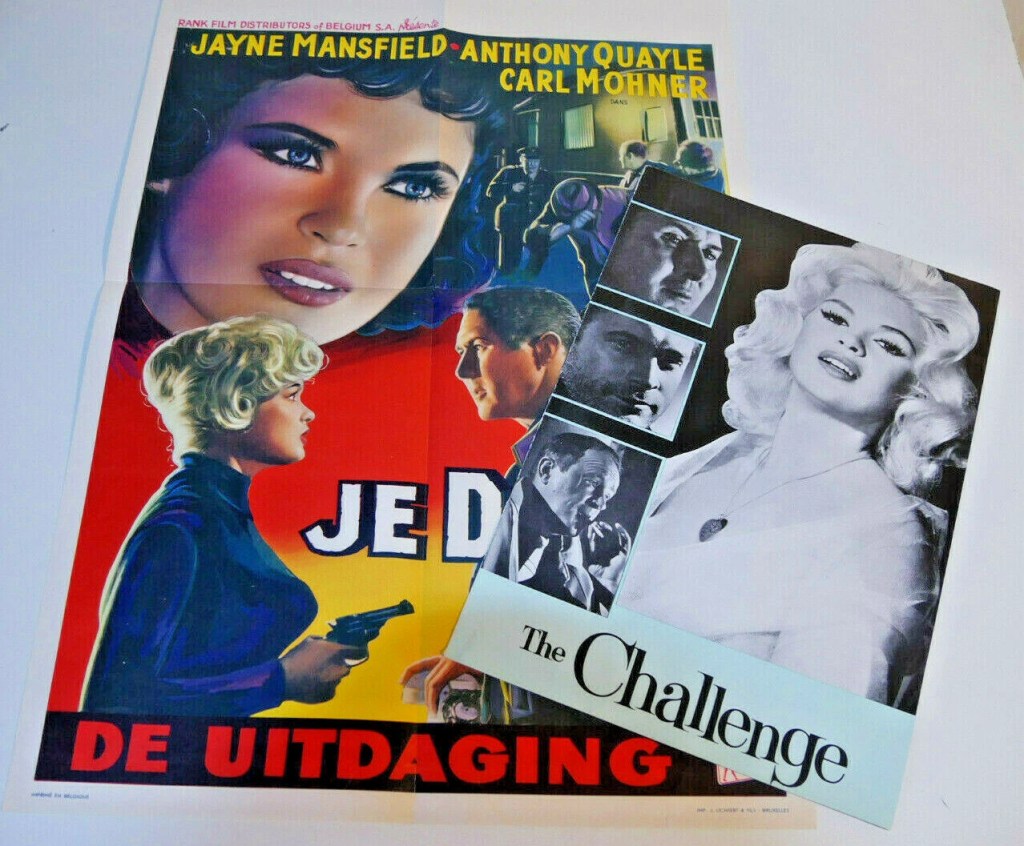

Extremely dark-edged thriller at least a decade ahead of its time. Absolute corker of a sting in the tail. Instead of being the gangster’s moll, Jayne Mansfield – following on from another British-made thriller Playgirl After Dark / Too Hot to Handle (1960) – turns the genre on its head by playing the smart leader of a gang of bank robbers constantly evading detection by the police. Anthony Quayle (East of Sudan, 1964) drops his good guy stiff upper lip screen persona in favor of a villain.

Most heist movies either fall into the category of mostly heist (Topkapi, 1964) and half-heist and half-aftermath. Here the heist is dealt with pretty quickly and then we’re into a complicated aftermath with double cross the order of the day. Even the supposed good guys – a cop and a union leader – have a distinctly mean streak. And on top of that we have a whole load of car chases. Just one would be unusual at the time for this budget category, but here we have three, complete with crashes and cars totaled off the road. And on top of that there’s an exceptionally creepy attempt at getting an inconvenient young child to commit suicide by playing chicken on a railway line.

Widowed lorry driver Jim (Anthony Quayle), who has dreams of owning a farm, is seduced into acting as the driver for the latest bank heist organized by Billy (Jayne Mansfield). While his van loaded with the loot tootles off unimpeded, she acts as bait in another car to snooker the cops into pursuing the rest of the gang. As proof of her love for him, she entrusts him with burying the loot in a place of his choosing.

He doesn’t get the chance to dig it up again because someone’s snitched on him, most likely Billy’s ex Kristy (Carl Mohner). And since he can’t snitch on the gang to save his own skin he ends up doing a five-year stretch. When he comes out, he finds the cops shadowing his every move, and Kristy taking his place in Billy’s bed. Det Sgt Gittens (Edward Judd) decides to play dirty by suggesting that Jim is intent on double-crossing her.

The gang, determined on recovering the loot as soon as possible, have their own arsenal of dirty tricks, beating up Jim’s mother and kidnapping his son. You’d think that with his mum black and blue and his son in the hands of the crooks that Jim would give up the loot. But, as I said, he’s not a good guy and is willing to risk all he supposedly holds dearly to get his hands on the dosh.

There’s a twist that Thunderbolt and Lightfoot (1974) later down the line exploit. Instead of someone building a school over the hiding place as with the Clint Eastwood picture, here it is hidden under dozens of barrels of high explosive encased in barbed wire. With the deadline approaching for killing his son, Jim attempts to enlist a bunch of local laborers only to be stopped in his tracks by the bureaucracy of a union shop steward.

Meanwhile, the couple, and despite all the motherliness of the childless wife (Barbara Mullen), forced to hide the child aren’t making the slightest attempt to help him escape. Instead, we watch with incredulity as one of the hoods, stumbling upon an easy way to get rid of a body, tempts the child into playing the aforementioned game of chicken.

Tension remains at a peak all the way through, in part because audiences are expecting Anthony Quayle to rouse himself from the depths of criminality and do the right thing, but mostly, in the template that Christopher Nolan would follow, three sets of narrative constantly come together.

There are two stings in the tail. Firstly, the burial site is obliterated when the barrels of high explosive shoot sky high. Secondly, with decided relish, Sgt Gittens informs Billy that the cops recovered the loot years before, so he’d risked mother and son for nothing. You can’t get blacker irony than that.

Jayne Mansfield was a much bigger attraction than Anthony Quayle and she puts in a superb performance as the mastermind and the practical woman, not willing to put career or love life on hold while Jim does his time. And while she’s slinky enough and occasionally brazen, she’s also decidedly human, but no more inclined than Jim to allow anybody to get in the way of the rewards of crime.

Like the crime pictures Britain showed a distinct aptitude for in the 1970s – Get Carter (1971), Villain (1971) and Sitting Target (1972) – this stays resolutely on the wrong side of the fence with not a single redeemable character.

Written and directed by John Gilling before he shifted into horror (The Reptile, 1966), this is a more than able piece, pulling no punches and resisting the temptation to sneak in any sentimentality.

Minor gem.

Catch it on Talking Pictures TV.