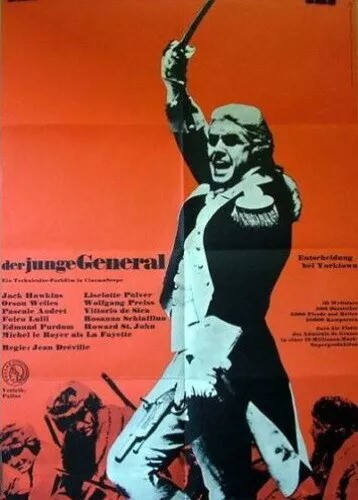

We are so accustomed to Hollywood rewriting every other country’s history it comes as a something of a surprise when they get a taste of their own medicine. And in such elaborate style. At the time this was by some distance France’s most expensive movie, a roadshow production made in Super Technirama 70, the widescreen technology favored by productions as diverse as Walt Disney’s animated The Sleeping Beauty (1959), Biblical epic Solomon and Sheba (1960), British drama The Trials of Oscar Wilde (1960), Samuel Bronston’s El Cid (1961) and Zulu (1964).

I wouldn’t have known from this picture how important a figure Lafayette was in French history. On a couple of forays to Paris I had placed no significance on shopping at the retail metropolis known as Galeries Lafayette. However, it turns out he was a major player in the French Revolution and helped to write the Declaration of the Rights of Man. But I wouldn’t have learned anything about his later career as this picture concentrates on his early life.

This long-lost restored picture was the official highlight of this year’s Bradford Widescreen Festival, mostly I assume because until the restoration it hadn’t been seen anywhere for half a century and because Bradford of all places is a sucker for restoration and its audience often includes more than a smattering of ex-industry professionals who can comment on its technical proficiency.

Although released in France in 1962 it didn’t cross the Atlantic or the English Channel until a few years later, but only for short selective engagements, during a period when there were was no shortage of roadshow material what with Its a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World still hogging Cinerama screens and My Fair Lady (1964) and The Sound of Music (1965) embarking on extensive runs.

This turned up in London in 1965 at the Casino Cinerama where How the West Was Won had played for over two years and it was also shown in Liverpool and enjoyed a couple of weeks in my home town of Glasgow at the Coliseum.

While the American alliance with France during the final stages of the War of Independence was critical to turning the tide against the British I suspect the exploits of the titular character (Michel Le Royen), an aristocratic stripling of 19 years of age, have become somewhat embellished in Hollywood Errol Flynn style.

The movie also ignores the irony that the principles of freedom and independence from regal rule spouted by many of the main characters came back to bite them several years later when the French Revolution sought to separate the brains of the aristocrats from their bodies. The French Emperor helped fund the American Revolution, assuming notions of independence were fine for foreign countries rising up against the British, a particular thorn in the French side at that point.

There’s also a considerable tinge of entitlement and for all its democratic principles the nascent new nation bowing down to the aristocratic breeding of the Frenchman and giving this inexperienced soldier the title of Major-General and putting him in charge of their least-disciplined troops, the irregular starving militia.

Never mind his age, he can hardly speak English and his aristocracy is hardly going to endear himself to his raw troops. And you can hardly ignore the ironic entitlement that when all other wounded men are left to look after themselves, our hero is carted off to George Washington’s (Howard St John) palatial servant-heavy mansion.

Still, according to this story and presumably the legend the young commander did indeed snatch defeat from the jaws of victory, in one engagement when his men were racing away in ignominious retreat he seized the torn American flag and inspired his men to return to battle and victory.

For a near three-hour picture it’s short on military action, though presumably that’s in the interests of historical accuracy so that means wading through countless scenes of politics both in France and America. In his home country he’s treated as something of a traitor for embarking on his own private war against the British. In America Congress is always on the back of George Washington, refusing him the funds and help he needs, insisting such would be in ample supply should he win a battle, the future President retorting back that victory would be guaranteed should he be given funds.

The absence of military set pieces is in part in recognition of the strategy endorsed by Washington, of avoiding a pitched battle with a superior enemy in favor of a guerilla war of attrition. There are more scenes of thousands of extras marching than of them engaging in any meaningful activity, though I’m assuming that could have been a budgetary restriction.

Whether’s it’s true or not there’s some clever stuff on the French political scene, the Emperor Louis XVI (Albert Remy) prone to taking advice from his wife Marie Antoinette (Liselotte Pulver) whose ear is being bent by La Fayette’s wife (Pascale Audret) but the self-serving attitudes on both sides will be recognizable to everyone.

There’s a stab at an all-star cast, Jack Hawkins (Lawrence of Arabia, 1962) as the British commander Cornwallis though the director – or perhaps the star himself given his idiosyncratic ways – has rendered Orson Welles as American ambassador Benjamin Franklin virtually unrecognizable, even his noted diction smothered.

The torch of freedom never had a more handsome advocate than in the hands of Michel Le Royer but it’s virtually a one-note performance though admittedly nobody expected much more from Errol Flynn.

Directed by Jean Dreville (Queen Margot, 1954).