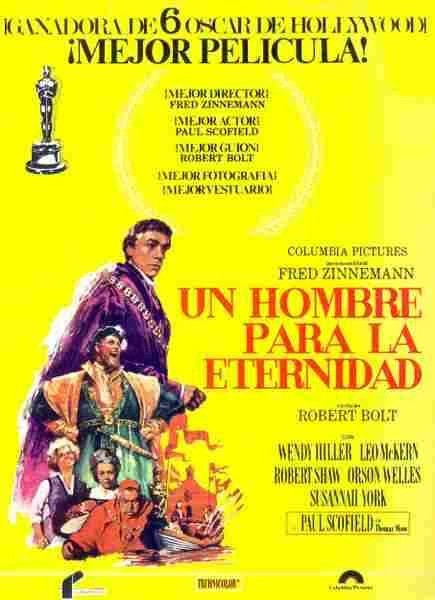

Columbia offset the gamble of turning an award-winning play with a stage star with no movie marquee luster, a co-star who had just about the same pulling power for audiences, and a host of actors nobody had ever heard of by cutting the budget to the bone – the $ 2million spent would barely be enough for a mid-level Hollywood production – even though director Fred Zinnemann belonged in the upper reaches of the Oscar hierarchy with one win and six nominations to his name.

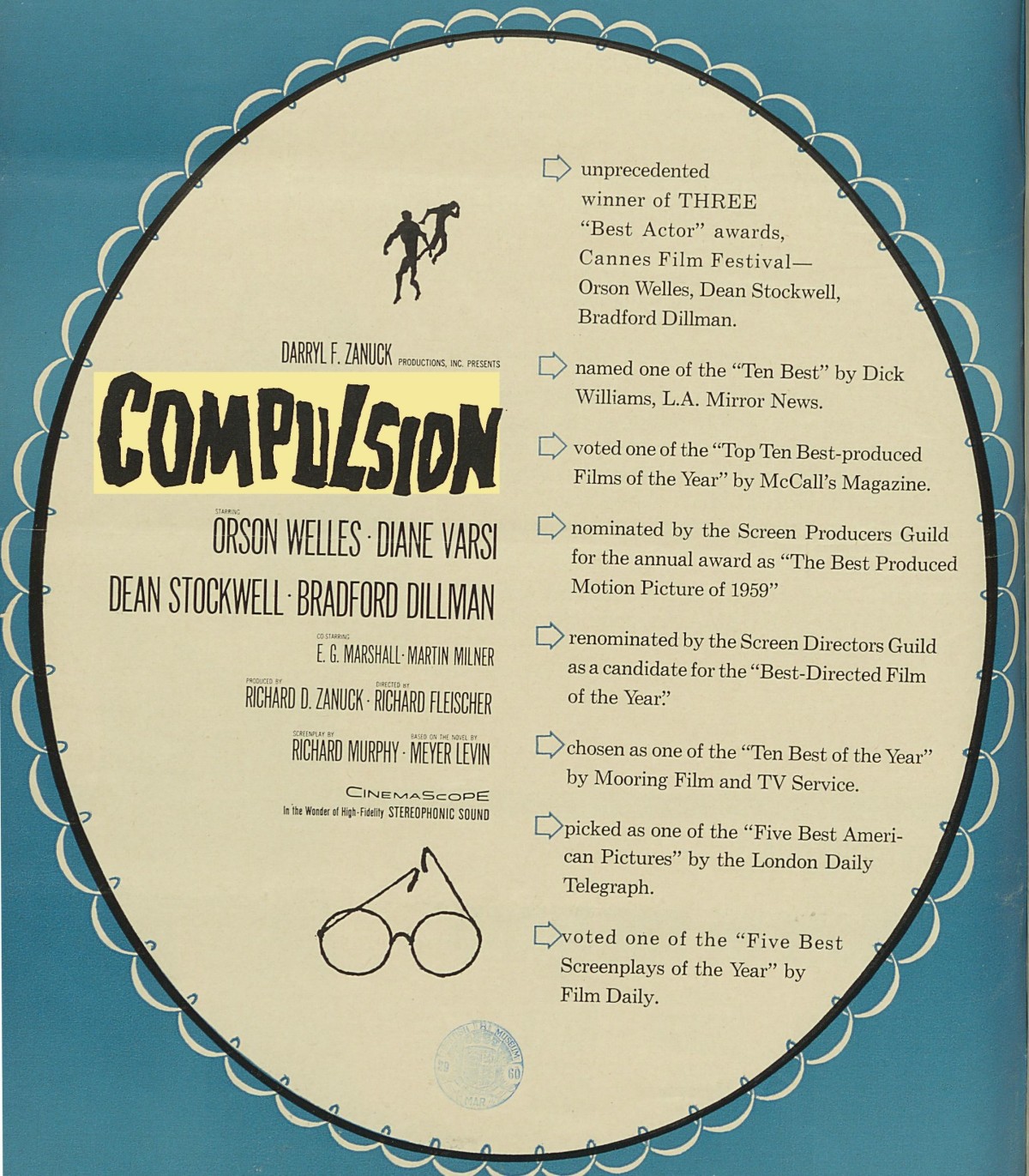

You could even argue that the best-known person in the cast was female lead Susannah York (Sands of the Kalahari, 1965, The 7th Dawn, 1964) or the legendary Orson Welles or even screenwriter Robert Bolt, acclaimed for his work on Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and Doctor Zhivago (1965).

Movie audiences of the period would be hard put to even recognize male lead Paul Scofield, in only his second major screen role after The Train (1964), while Robert Shaw had little more popularity unless you were familiar with From Russia with Love (1963) in which he played a bad guy and Battle of the Bulge (1965). There was a fair chance that Scofield could hit the mark among the upscale stage audiences in London and New York, where he had won a Tony. The play, by Robert Bolt, had proved substantially more popular in terms of length of run and critical esteem in New York than London.

But Zinnemann hadn’t made a picture in six years, not since The Sundowners (1960), having become embroiled in two projects The Day Custer Died (never made) and Hawaii (made but without him) without anything to show for it.

This was a virtue-signaling picture long before the term became over-used. England’s Lord Chancellor Sir Thomas More (Paul Scofield) makes a principled stand against King Henry VIII (Robert Shaw). From today’s perspective, the principled stand is more complex. The idea that the ruler of a country would have to bend the knee to the leader of a religion would not sit well today. You might be unlikely to blame Henry VIII for wanting to break the rules, given he was in dire need of a male heir that his current wife could not supply, especially as without said heir the country would most likely fall into civil war.

You could make a case for Henry VIII being the heroic one, standing up to the Pope, who, for political reasons, as much as anything else, refused to annul the king’s existing marriage. When the Pope didn’t see it the king’s way, Henry VIII decided the only alternative was to break away from the Catholic Church and set himself up as the secular head of the church in England.

And although Thomas More has a fair following today for his philosophy – he wrote Utopia – Robert Bolt was guilty of leaving out aspects of his character which were more unsavory. He was a prime mover in the persecution of Protestants, condemned as “heretics,” but that’s been excised from the story told here in order to present Thomas More as a man of conscience.

Apart from the verbal duel between More and Henry VIII, there’s a rich backdrop of political machination bringing in such names as Thomas Cromwell (Leo McKern) – of Wolf Hall fame – Cardinal Wolsey (Orson Welles), the Duke of Norfolk (Nigel Davenport), William Roper (Corin Redgrave) and Richard Rich (John Hurt). There’s corruption, bribery and betrayal and at times it appears that More is the only one to place any significance on the law.

But More’s no innocent, he’s well used to playing the political game and arguing his case. He only becomes undone by his stand against a king who will brook no opposition.

Paul Scofield has a fine time of it with a well-developed character, gently spoken, appealing to sense and sensibility, and generally well loved by the populace. Although in retrospect I think other Oscar nominees Richard Burton for Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf and Michael Caine for Alfie might have been more deserving of the Oscar gong.

Robert Shaw makes a fine opponent, tempering the monarch’s known bluster with a sense of humor. While Paul Scofield tended to steer clear of Hollywood except for films like Scorpio (1973), Robert Shaw went immediately into the male lead in Custer of the West (1967) and eventually became a genuine draw.

The uncredited Vanessa Redgrave (Blow-Up, 1966) was otherwise the star-picker’s pick. Future years would invest greater luster in the supporting cast. John Hurt (Sinful Davey, 1969) the first to be given a tilt at marquee splendor. Leo McKern (Assignment K, 1968) achieved small-screen deification through Rumpole of the Bailey (TV series, 1978-1992). Colin Blakely (The Vengeance of She, 1968) played Dr Watson in Billy Wilder’s The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes (1970).

Robert Bolt deserved his Oscar for the considerable work he put in to converting his stage version for the screen. The staging looks quite stagey to me, but Zinnemann did an excellent job of adding the necessary richness and ensuring the tale was rounded-out.

Not sure I’d place it in the Top Fifty Best-Ever British Films, but it’s still enjoyable even though you might take issue with the issues presented.