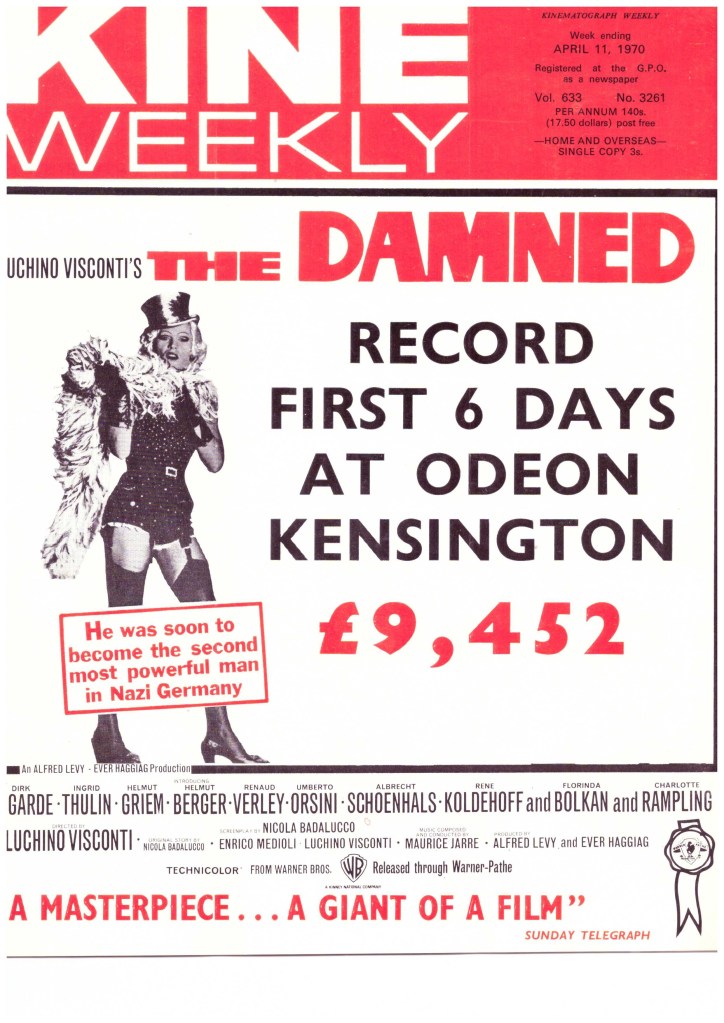

Ponderous, gratuitous, offensive. Let’s start with the pedophile, spoiled grandson Martin (Helmut Berger) of industrialist patriarch Joachim (Albrecht Schonhals). We already guess he has this kind of predilection for young girls as that’s suggested during a game of hide-and-seek at the family mansion and by a scream in the night that is ignored. He keeps a mistress Olga (Florinda Balkan) and is drawn to the young girl in the apartment next door, bringing her the kind of expensive present that her impoverished mother believes she must have stolen. So we know what he’s all about. It’s discreetly enough stated without the inclusion of a scene which I doubt would pass the censor these days and should the young actress be still alive in these MeToo times might be considering legal action for being taken advantage of.

Although the storyline is similar to the director’s earlier The Leopard (1963) of the powerful – there a wealthy landowner, here an arms manufacturer – trying to hold onto their status in times of change (then the invasion of Sicily by forces wanting to unite Italy, now the rise to eminence of Hitler), there’s little of the cinematic flair of the latter. Long scenes are played out at dinner tables or in bedrooms. And most of that is machination, someone or other wanting to take over the family firm or be the power behind the throne.

You need some knowledge of German history to understand the significance of some events. Hitler, then the German Chancellor, burned down the Reichstag (the German Parliament) in 1933 in a ruthless bid for power. Hitler employed two factions, the predominantly working class brownshirts (the SA) and the mainly middle class blackshirts (the SS), the former a paramilitary organization committed to actions against Jews and backing his early bid for power. In 1934, in the Night of the Long Knives, the SS obliterated the SA.

The first section of the picture straddles these two events with a Succession-style drama. In reaction to the burning of the Reichstag, Joachim replaces Herbert (Umberto Orsini), his top executive and outspoken anti-Nazi, with boorish nephew Konstantin (Reinhard Koldehoff) who is a high-ranking member of the SA.

This doesn’t sit well with Friedrich (Dirk Bogarde), who expected preference. Urged on by lover Sophie (Ingrid Thulin), Joachim’s widowed daughter-in-law, and Aschenbach (Helmut Griem), Joachim’s nephew and an ambitious high-ranking SS official, Friedrich kills Joachim but pins the blame on Herbert who has to flee.

Konstantin is thwarted because although technically in charge it’s now Martin who owns the business and nudged by Sophie gives Friedrich the top management role. So Konstantin resorts to blackmail, having uncovered the pedophile. In steps Sophie who uses Aschenbach to thwart him again. Though there’s not much need because Konstantin is eliminated as one of the SA members executed in 1934 at some kind of gathering where the attendees all appear to have homosexual tendencies.

Aschenbach and Martin nurse grievances. Aschenbach feels Friedrich isn’t ostentatious enough in support of Hitler and Martin is furious that Sophie manipulated his difficulties with Konstantin to Friedrich’s benefit. So the SS man and the dissolute conspire. In the way of this kind of heightened melodrama it’s revealed that Friedrich killed Joachim. That doesn’t send Friedrich to trial, instead wins him a get-out-of-jail-free card by turning into a radical Nazi.

Martin, meanwhile, is also a member of the SS. He rapes Sophie, Friedrich loses his way and in one of those moments Francis Ford Coppola would appreciate Martin kills them on their marriage day.

There are a couple of oddities. It’s hard to believe a young girl – we’re talking a 7-8-year-old – would actually manage the mechanics of hanging herself. And when Friedrich is drawn into joining the slaughter of the SA members, there is over-emphasis on his perceived sensitivity when previously he had cold-bloodedly despatched Joachim.

So glorified soap opera with too much virtue signalling for its own good. Excepting Herbert and wife Elizabeth (Charlotte Rampling) and another grandson, who play minor roles, there’s not a single character to care for.

Despite the unusual backdrop, there’s nothing particularly unusual about the succession/inheritance scenario. The tough self-made millionaire or latest head of a wealthy family seeks to maintain power and guard against diminishing its status and lineage by ensuring the correct successor is groomed and that capital is not dissipated through unsuitable marriage or indulging weaker offspring. Thomas Mann, who fled the Nazis in the 1930s, covered this ground more successfully in his debut novel Buddenbrooks, although admittedly with less decadence.

Setting The Damned against the rise of the Nazis is an attempt to give it more artistic status than it merits because it’s really not much more than a standard study of ambition and ruthlessness.