Otto Preminger was initially beaten to the punch, rights to Francoise Sagan’s 1954 bestseller already sold to Ray Ventura, forcing the director to ante up $150,000 a year later to retrieve them. The director started working on the script with S.N. Behrman (Quo Vadis, 1951) but, dissatisfied with the result, turned to Arthur Laurents (Rope, 1948), who was permitted to complete his screenplay without any interference.

Shooting began in July 1957 in Paris and locations included Maxim’s and jazz club La Hachette where Preminger filmed Juliette Greco singing the title song. The main locale, a villa in Le Lavandou in the South of France, was rented from French publisher Pierre Lazareff.

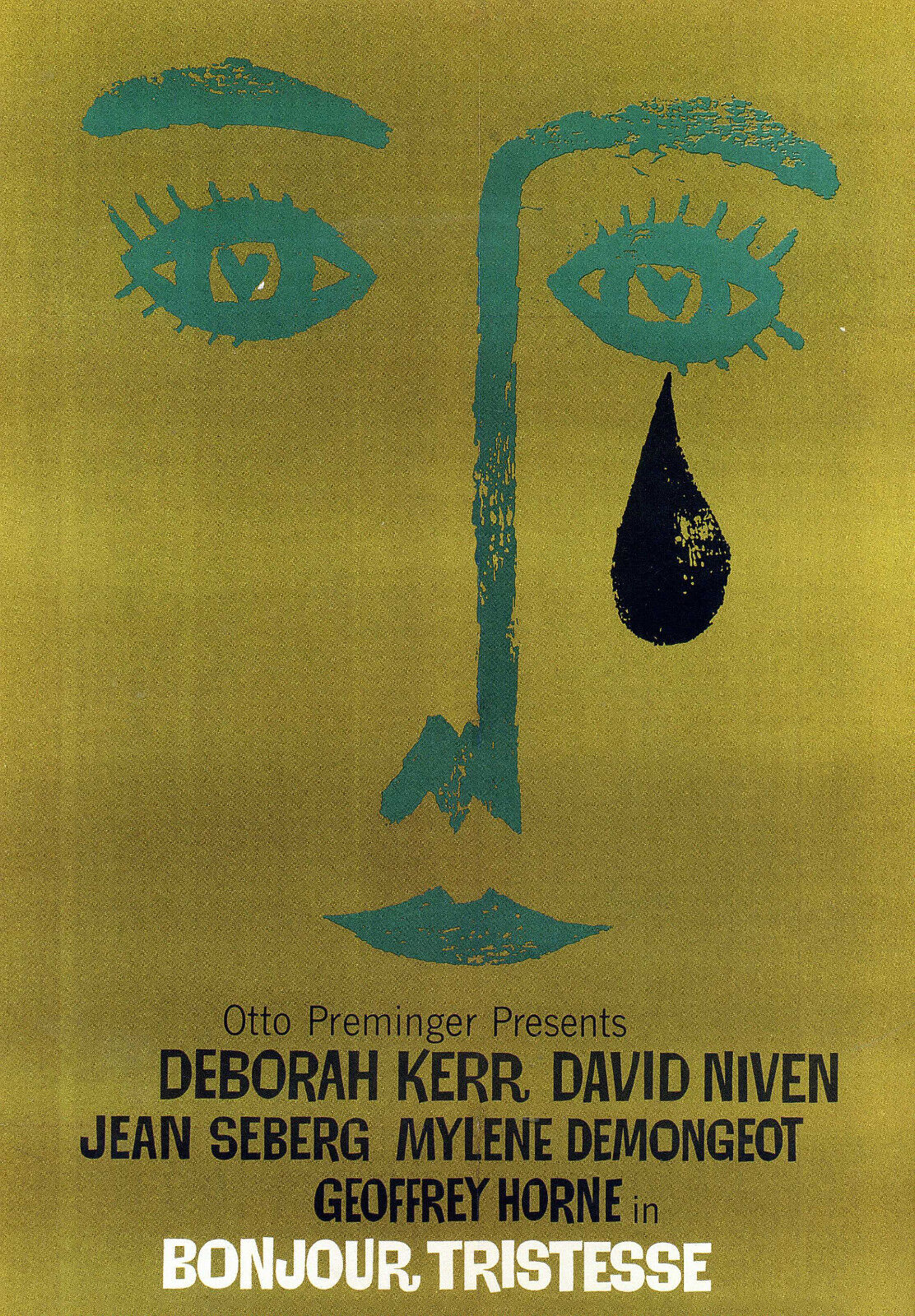

By casting Deborah Kerr (The Night of the Iguana, 1964) and David Niven, who had starred in The Moon Is Blue (1953) as principals, it was officially turned into a British production, providing access to Eady Levy monies, although it was shot with a French crew who proved largely hostile to the director’s personality and went on strike on the second day. Due to a scheduling misunderstanding, Niven and Preminger got off on the wrong foot.

But the chief victim of the director’s ire was Jean Seberg, star of his previous effort – and substantial flop – Saint Joan (1957). While not entirely happy with the neophyte’s performance in her debut, he decided to give her the benefit of the doubt. “I refused to believe that I was so wrong and the critics so right, that this girl was so completely devoid of talent,” he complained, offering her a second chance. “He showed a faith in me nobody expected him to show,” commented a grateful (at the time) Seberg.

But Preminger soon regretted his decision. “I don’t like the way you talk, walk or dress,” he told her. Unable to get a better performance from her after four or five takes he would just give up. At one point, she was drenched with buckets of water for a scene where she was emerging from the sea. However, that scene only took seven takes, something of a triumph for Seberg. And it’s worth noting that seven takes was nothing for Preminger if he really wanted to make an actor suffer.

If you think the movie takes a very melodramatic turn, the screenplay toned down much of the book’s melodrama and especially its more serious overtones. Preminger stuck to the script. He invented camera movement and blocking during the day’s rehearsals rather than arriving at the studio with fixed ideas. To allow the camera to move more freely, the floor of the set was treated with gelatin. He relied on only a few takes, expecting the actors to deliver what he wanted, so in some respects it was no surprise he reacted badly when Seberg failed to follow his instructions, although as a last resort he knew he could always cut to another actor.

Niven and Kerr both braced the director about his treatment of Seberg, telling him “to lay off this girl, because she’s had it, and if you continue, we don’t want to keep working. ”

The movie was completed at Shepperton Studios in England. The last shot of the film took an entire day to shoot, Cecile removing her makeup with cold cream in front of the mirror and tears form. Preminger wanted “the face to remain a child’s face.” Two days of flashback shoots had to be re-done as they had by mistake been processed in color rather than black-and-white

Preminger should have been a happy man. He was falling in love with costume coordinator Hope Bryce, a model who had worked with Givenchy, and in due course she became his third wife. Ditto, Seberg, who had fallen for lawyer and nobleman Count Francois Moreuil – a relationship that also ended in marriage – and as a result of the romance grew more relaxed on the set and “didn’t let Preminger’s demands bother her.”

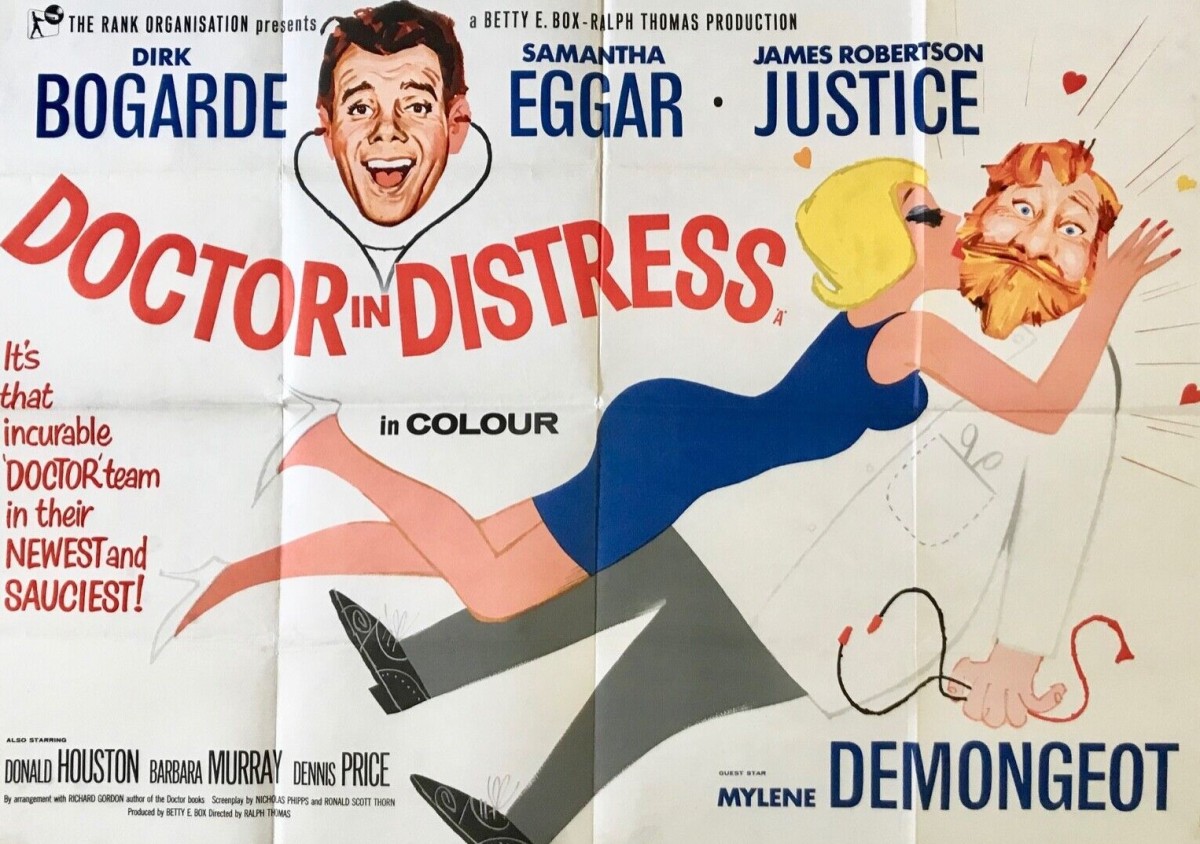

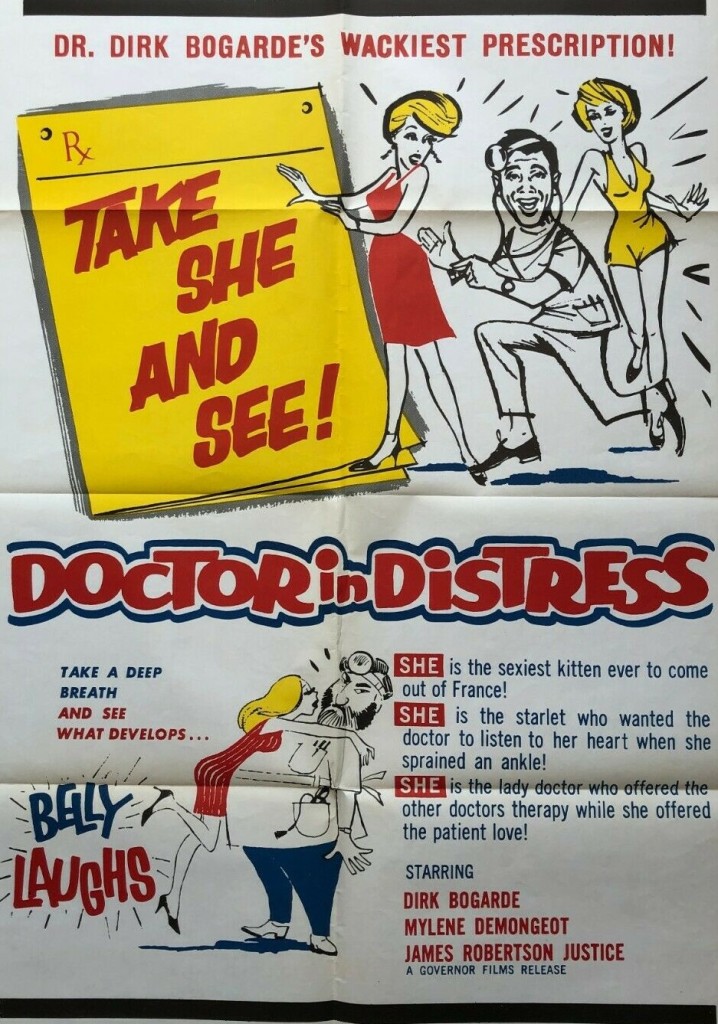

Opinions differ regarding Seberg. Arthur Laurents deemed her “a shrewd cookie, I don’t care what they say about her.” Deborah Kerr averred: “I think any other woman would have collapsed in tears or walked out, but she took calmly all the berating and achieved a very interesting and true Sagan-type heroine.” Co-star Mylene Demongeot said, “For a while she had everything in her hands to have a successful career.” From Seberg’s perspective she viewed Preminger as a father figure, with the attendant hate that often comes with that.

Demongeot, however, fought fire with fire, calmly warning the director he would get a heart attack if he kept on yelling at her. Standing up to him and occasionally dissolving into fits of laughter at his instructions kept him at bay. She saw a different side of the director, although tagging him as “ a nasty man,” she also recalled him as “a very funny, intelligent man…and he could even be charming…outside of work.” Seberg and Demongeot had become friends after the American had stayed with the French actress and her husband in order to learn the lines of French required for her role.

After filming ended, Preminger’s current wife Mary Gardner sued for divorce and Twentieth Century Fox threatened to take him to court for repayment of $60,000 for a film bever made. Preminger sold Seberg’s contract to Columbia. “He used me like a Kleenex and threw me away,” said Seberg. But, interestingly, it was only after that relationship ended that she took acting lessons.

In truth Seberg’s Hollywood career never recovered although she enjoyed a brief mainstream revival a decade later through Paint Your Wagon (1969) and Airport (1970). Hollywood has its revenge on Preminger. After the failure of Skidoo (1968), Paramount chief Charles Bluhdorn exacted “a very slow death” on the director.

NOTE: There’s an update to this called Part Two which is published on Oct 19, 2023. When I did this original article I didn’t have my normal online access which permits me to check through trade magazines. Because I received a query about box office I decided, once the online issue had been cleared up, to check that issue and in the process I uncovered so much fascinating information I took a second stab at it.

SOURCES: Chris Fujiwara, The World and Its Double, The Life and Works of Otto Preminger (Faber and Faber, 2008) pp210-217; Eric Braun, Deborah Kerr ( W.H. Allen , 1977) pp164-165; Garry McGee, Jean Seberg, Breathless, Her True Story, (2017) pp42-48.