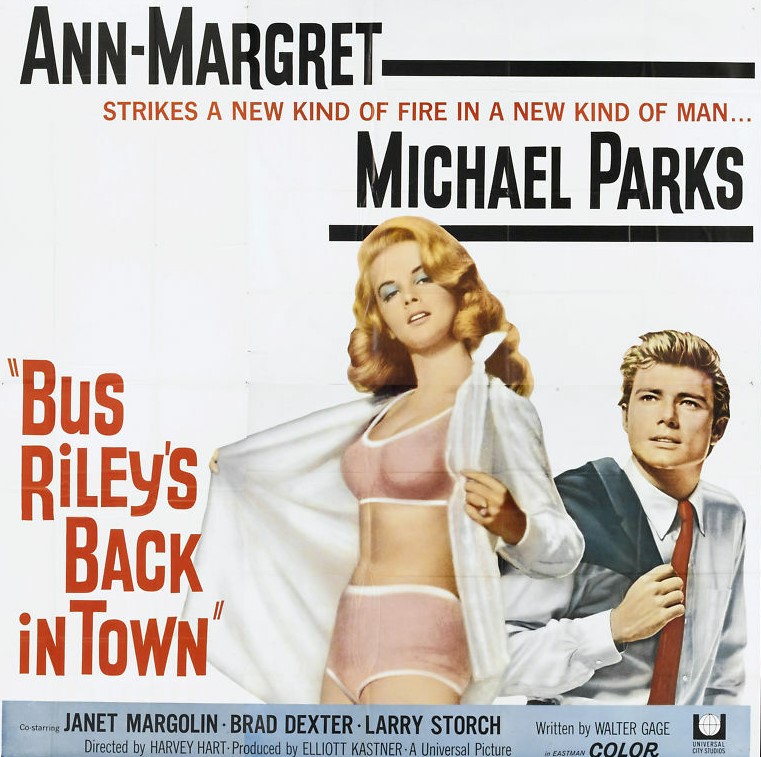

Given Ann-Margret receives top billing I had automatically assumed she was the Bus Riley in question. Although decidedly the female lead, her role is secondary to that of a sailor returning to his small town. The backstory is that Bus – no explanation ever provided for this nickname – Riley (Michael Parks) had been too young to marry the gorgeous Laurel (Ann-Margret) before he joined the U.S. Navy and in his absence she married an older wealthy man.

Bus dithers over his future, re-engages with his mother and two sisters and finds he has not lost his attraction to Laurel. Although a handy mechanic, he has his eye on a white collar career. An initial foray into becoming a mortician founders after sexual advances by his employer (Crahan Denton). Instead he is employed as a vacuum salesman by slick Slocum (Brad Dexter).

While his sister’s friend Judy (Janet Margolin) does catch his eye, she is hardly as forward or inviting as the sexy Laurel who crashes her car into his to attract his attention. But the easy sex available with Laurel and the easy money from exploiting lonely housewives trigger a crisis of conscience.

Perhaps the most prominent aspect is the absence of good male role models. Bus is fatherless, his mother (Jocelyn Brando) taking in boarders to meet her financial burden – including the neurotic Carlotta (Brett Somers) – and while younger sister Gussie (Kim Darby) adores Bus the other sister Paula (Mimsy Farmer) is jealous of his freedom. Judy’s father is also missing and her mother (Nan Martin) a desperate alcoholic. The biggest male players are the ruthless Slocum and Laurel’s husband who clearly views her as a plaything he has bought. The biggest female player, Laurel, is equally ruthless, boredom sending her in search of male company, slithering and simpering to get what she wants.

Scandal is often a flickering curtain away in small towns so it’s no surprise that Bus can enjoy a reckless affair with Laurel or that a meek mortician can get away with making his desires so quickly apparent, or that behind closed doors houses reek of alcohol or repression. A couple of years later and Hollywood would have encouraged youngsters like Bus and Laurel to scorn respectability in favor of free love. But this has a 1950s sensibility when finding a fulfilling job and the right partner was preferred to the illicit.

In that context – and it makes an interesting comparison to the more recent Licorice Pizza that despite being set in the 1970s finds youngsters still struggling with the difference between sex and love – it’s an excellent depiction of small-town life.

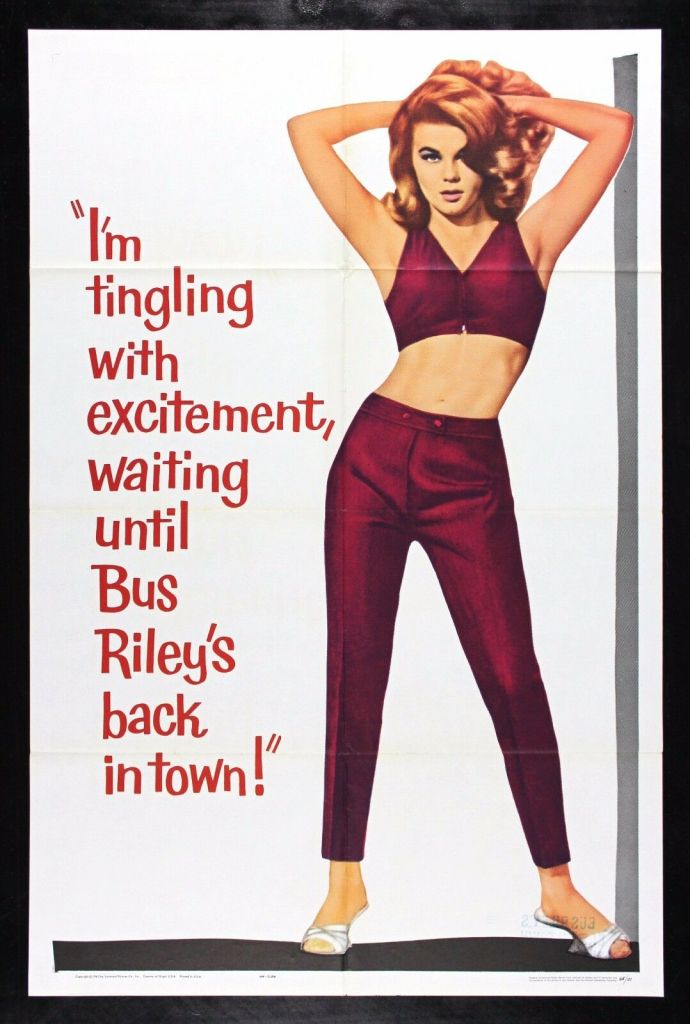

While Michael Parks (The Happening, 1967) anchors the picture, it’s the women who create the sparks. Not least, of course, is Ann-Margret (Once a Thief, 1965), at her most provocative but also revealing an inner helpless core. And you can trace her screen development from her earlier fluffier roles into the more mature parts she played in The Cincinnati Kid (1965) and more especially Once a Thief (1965).

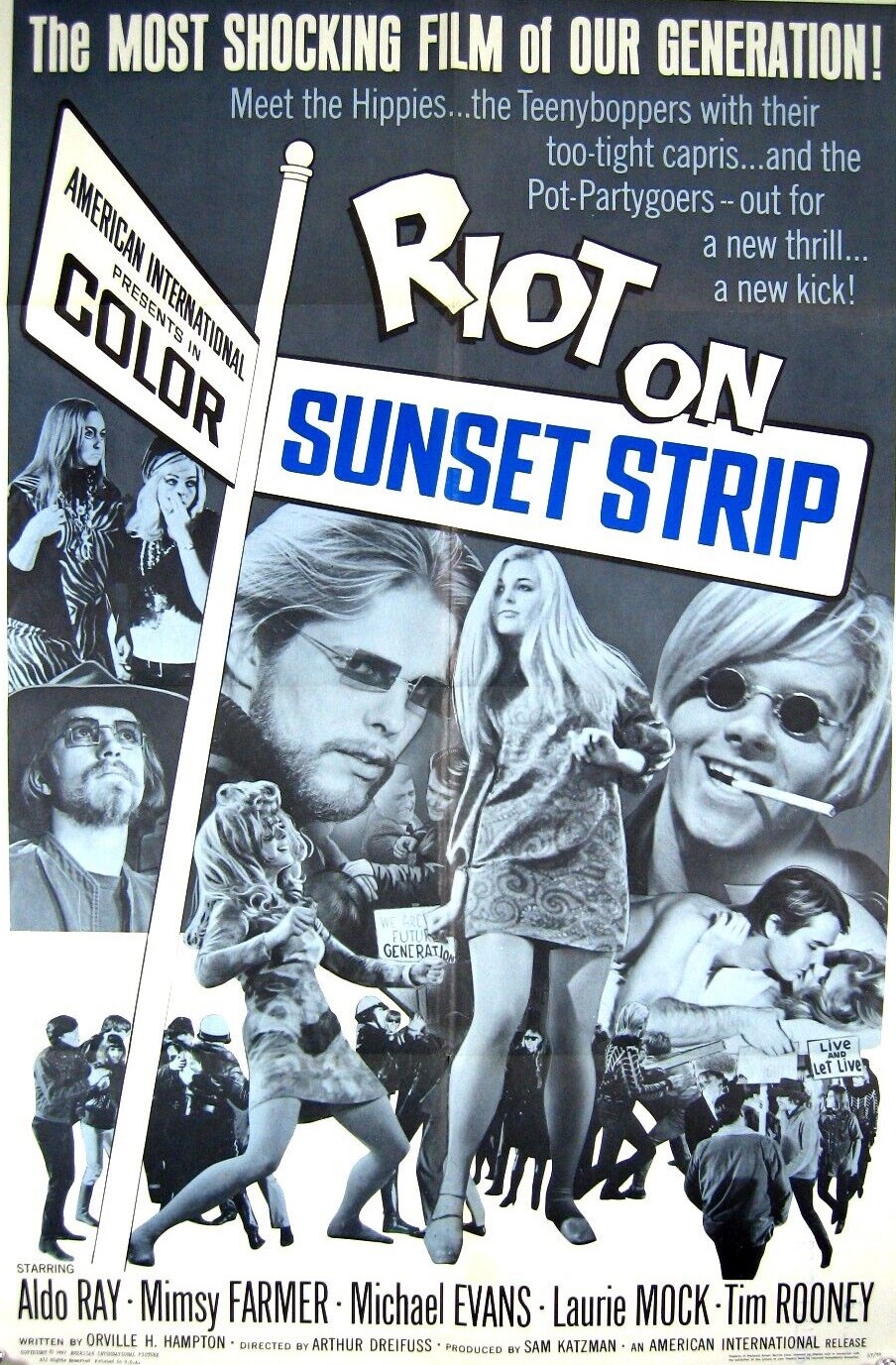

In her movie debut Kim Darby (True Grit, 1969) is terrific as the bouncy Gussie and Janet Margolin (David and Lisa, 1962) invests her predominantly demure role with some bite. Jocelyn Brando (The Ugly American, 1963) reveals vulnerability while essaying the strong mother. Mimsy Farmer (Four Flies on Grey Velvet, 1971) also makes her debut and it’s only the second picture for David Carradine (Boxcar Bertha, 1972). Brad Dexter (The Magnificent Seven, 1960) is very convincing as the arrogant salesman.

It’s also the first film for Canadian director Harvey Hart (The Sweet Ride, 1968) and he has some nice visual flourishes, making particular use of aerial shots. The scenes of Bus trudging through town at night are particularly well done as are those of Laurel strutting her stuff.

It was also the only credit for screenwriter Walter Gage. That was because Gage didn’t exist. Like the Allen Smithee later adopted as the all-purpose pseudonym for pictures a director had disowned, this was the name adopted when playwright William Inge (Oscar-winner for Splendor in the Grass, 1961) refused to have anything to do with the finished film.