Heavily-layered Claude Chabrol revenge thriller that concentrates as much on the tricks the human mind can play rather a string of unusual twists. Self-justification and redemption go hand in hand. The director sucks us in to sympathize with an obsessed killer on the grounds that his victim deserves to die and then at the end makes us question everything we’ve been led to believe.

As usual, with this director, there’s more than enough atmosphere and his exposure of small-town life in France and the flaws in families and relationships almost serve to turn this into more of a drama than a thriller. But then that is Chabrol’s distinctive trademark.

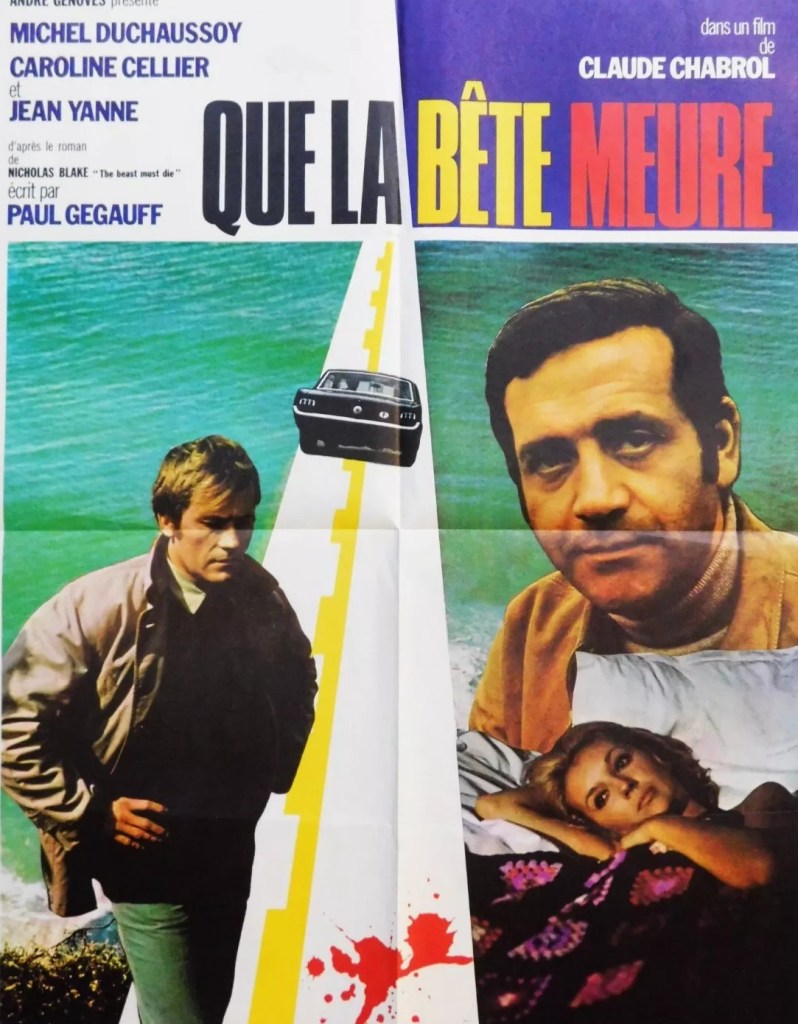

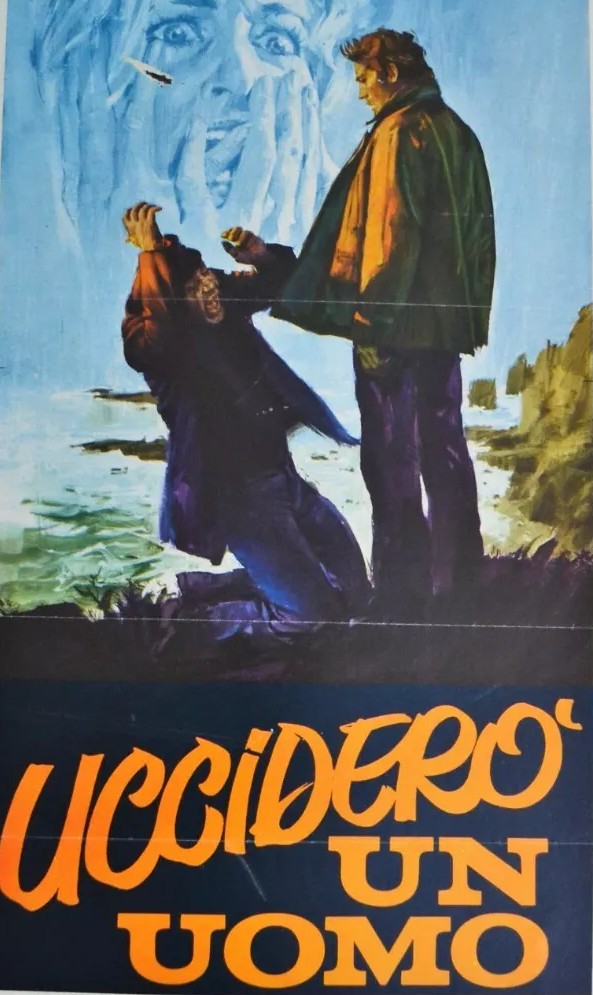

When the police fail to track down the hit-and-run driver who has killed the young son of Charles Thenier (Michel Duchaussoy), the father, an author, determines to find the killer and, as he confides in his diary, not report him to the authorities, but finish him off himself. He makes the smart deduction that since there was no trace of a repair to a damaged car, the killer must own a garage. By a stroke of luck, he discovers a well-known actress Helen Lanson (Caroline Cellier) was a passenger in the car. Hiding behind his pen-name Marc, he seduces Helene, who has been hit by depression as a result of the incident, and discovers the driver was her brother-in-law Paul (Jean Yanne).

Convincing her to allow him to accompany her on a visit to his sister, his self-justification rises a notch as he notes that Paul is exactly the kind of guy who might well come to a sticky end given the detestable way he treats his wife Jeanne (Anouk Ferjac) and teenage son Phillippe (Marc Di Napoli) and is a womanizer to boot. While Charles bonds with Phillippe, who reveals he wants to kill his father, his relationship with Helene takes a knock when he discovers she’s had a brief affair with her brother-in-law.

So Charles plans to stage an accident at sea but Paul is one step ahead. The driver has found Charles’ diary and has taken a gun on the sailing trip to defend himself. But after Charles and Helene leave, Paul is discovered dead by poisoning. Charles’ diary makes him a suspect. And while he argues that it would be foolish of him to disclose his plans to a diary that is in the dead man’s possession, the police take the view that that would exactly what a clever murderer would do to deflect suspicion.

The police can’t find the poison so Charles is released. Phillippe confesses to the murder. But there is a further twist. The tale on which this is based was called The Beast Must Die, and from the various revelations we would be assuming that the beast in question, the remorseless despicable hit-and-run driver with not a single redeeming feature would be the most likely to fit this category.

But on reflecting on his own obsession, Charles clearly realizes that he is as likely a candidate to be termed a “beast.” It turns out he has let the son take responsibility for the murder and now he sets out to make amends, confessing to Helene that he did it and then heading off to sea presumably to jump overboard at a suitable spot.

Justified killing is never, it turns out, justifiable because in reality it turns the innocent into the guilty, and there’s little distinction between killers. When we cast our minds back, we become aware, as he does, that Charles has transitioned from grieving father to ruthless seducer of a vulnerable woman, preyed on a youngster who in consequence of their supposed friendship is happy to carry the can so Charles can escape, and is in any case going to complete his plan regardless of the cost to others.

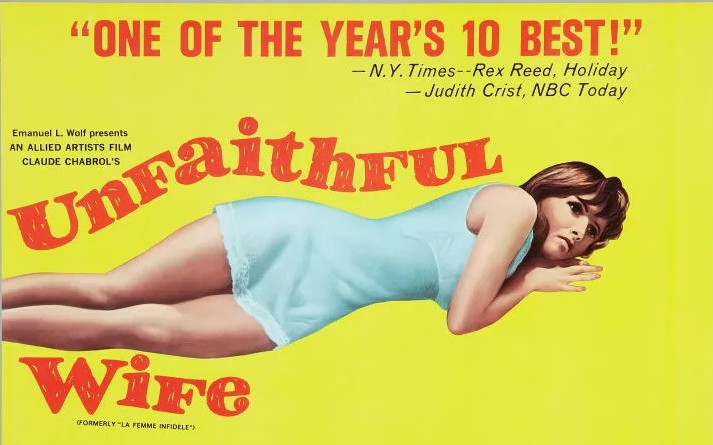

Michel Duchaussoy (La Femme Infidele, 1969) steps up to the plate. The supporting cast are excellent. After the abysmal Road to Corinth (1967), Claude Chabrol established his name as the inheritor of the Hitchcock mantle after this and La Femme Infidele. Written by the director and Paul Gegauff (More, 1969) from the novel by Nicholas Blake (the pen-name of Irish poet Cecil Day-Lewis, father of Oscar-winning actor Daniel Day-Lewis).

No shortage of tension, upends your expectations, totally involving.