Despite an exceptional and Oscar-nominated performance by Stuart Whitman (Rio Conchos, 1964) , I suspect modern audiences will take less kindly to this tale of convicted child molester trying to come to terms with his feelings. At least it’s considerably more honest than the creepier May December (2023) where the criminal steadfastly contended her innocence.

And I suspect, too, that Whitman’s square jaw and muscular physique got in the way of his attracting the parts for which the depths of vulnerability he was able to exhibit were most suited. He came to this straight after an action role, as the charming bad-good-guy of The Commancheros (1961) where, as far as audiences were concerned, what he did with his fists was more important that what he expressed through his eyes.

There’s a bit of a grey area that lends the convicted Jim Fuller (Stuart Whitman) the benefit of the doubt. He was found guilty of intent not of actual molestation and a goodly part of the picture is spend on examining why he went down that route, either in a group exercise in prison or one-on-one with a psychiatrist, chain-smoking Irishman Dr McNally (Rod Steiger) in both instances.

I’m not sure how the psychiatric evidence adds up, but basically, with a dominant mother who bullied his father, he grew up frightened of women, despite being attracted and attractive to them, and sought out someone with whom he felt more comfortable, less challenging, leading him to spend too much time watching children at play and eventually buying a young girl an ice cream and going out on walks with her.

It would have been too much for audiences of the time – as it even was with May December – to go into the technicalities of what he intended to do so we are left to trust his own word that he never intended to instigate anything sexual, though why kidnap a child in the first place. The second element that would fill modern audiences with alarm is that though he manages to begin a sexual relationship with a woman of his own age, secretary Ruth Leighton (Maria Schell), she is a widow with a young daughter. Most people would instantly come to the conclusion he was using mother to groom daughter.

However, the film takes the tack that he’s using the daughter to explore a normal relationship with a child, the joy of having a daughter, and the delight and happiness that a young person can bring into a dour repressed life. Dr McNally keeps on banging on that Fuller is “cured” but it’s a very uneasy watch trying to work out if he is or not.

In the event, the first time he’s alone with the girl he is photographed by a local journalist who sticks the photo on the front page, destroying the life Fuller has carefully rebuilt. He has found employment as an accountant with a sympathetic business owner Andrew Clive (Donald Wolfit), fitting in so well he is promoted, though at odds with another senior employee Roy Milne (Paul Rogers). He is chucked out of his accommodation, loses his job and although Ruth initially stands by him the minute she sees Fuller with her daughter her instincts are hostile.

There would be no point in an actor trying to gain sympathy for such an unsympathetic character by playing to the gallery with bouts of temper or floods of self-pitying tears, but even so, the vulnerable husk Whitman presents, his struggles with his self-contempt, his understanding of the feelings he must invoke, his determination to live as quietly as possible, almost in that determined English manner of never being heard nor seen, is what makes this film. Interestingly, he replaced Richard Burton, who pulled out at the last minute (as did Jean Simmons) and you could easily imagine with those trademark quick intakes of breath and deep growls how that actor would have played the part.

Whitman doesn’t go near any grandstanding. It’s just a heartfelt performance of a man who’s lost his way and knows he might never find his way back, haunted by his past, unable to trust himself, unable to believe that he is, in fact, cured. Probably, the biggest issue is that the movie comes down on his side, especially when he becomes one of the usual suspects in another crime involving children, though he did not commit that, and tries to suggest that a child molester will find salvation through living with a mother and child in the normal fashion. As I said, this is not my subject of expertise, thankfully, and that may be well what’s advocated rather than staying away from children altogether.

While the approach might be considered a shade naïve at the same time it does examine issues surrounding reintegration and avoids the obvious trap of attempting some kind of character redemption.

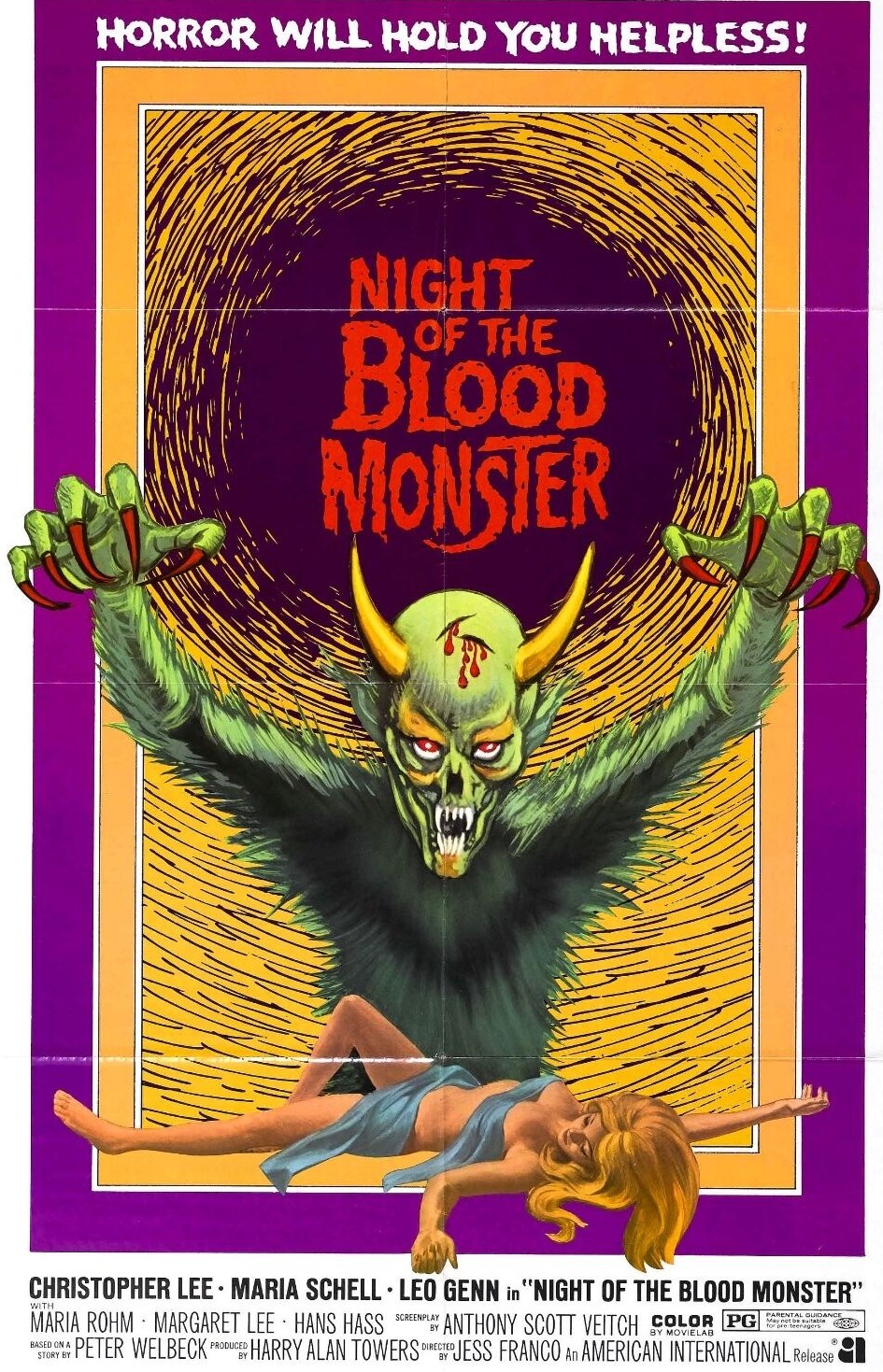

Apart from Whitman, there are good performances all round. Maria Schell, whose career within a decade would go from roadshow blockbuster Cimarron (1960) to WIP epic 99 Women (1969), subsumes her normal more glamorous persona to play a believable working mother. With his chain-smoking, Rod Steiger (The Pawnbroker, 1964) is allowed to fidget to his heart’s content but even such obvious scene-stealing only places more emphasis on the quieter Whitman. Donald Wolfit (Life at the Top, 1965), too, reins in his usual bluster.

Guy Green (The Magus, 1968) directed from a screenplay by Sidney Buchman (The Group, 1966) and Stanley Mann (The Collector, 1965) from the bestseller by Charles E. Israel.

In this instance, given the Oscar nom, Stuart Whitman could hardly be considered under-rated but over the years seems to have disappeared from sight.

Worth a look to see what he could do with the right material.