Wow! Here’s a find. High octane noir. Smorgasbord of illicit sex, alcohol, blackmail and murder. Noir without the traditional shadow and shading, reeking of sin, heading straight down the road to Exploitation City. Even redemption is tainted. Some quite stunning scenes, what it lacks in style makes up with juddering twists, out-doing Elmer Gantry (1960) as it barrels through fifty shades of hypocrisy. The title’s a bit of misnomer because there’s hardly a commandment that doesn’t get broken.

Following a car accident involving girlfriend Terry (Lyn Statten), business graduate Ted Mathews (Jonathan Kidd) loses his memory, hooks up with preacher Noah (Frank Arvidsen) and re-emerges as fire-and-brimstone evangelist Tad Morgan, a huge success on the circuit, especially when he calls upon (presumably fake) healing powers.

Seven years later Terry is close to Skid Row, her vicious tongue no match for the vicious punch of lover Pete (John Harmon) who rolls bums to keep them in booze. When by coincidence she happens upon Ted/Tad, she wants revenge. Because he ran away from the accident, she took the rap and served a prison spell for drunken driving. So she indulges in a spot of blackmail.

Ted/Tad, on rediscovering his identity, is hit by a shed-load of guilt because he believes he killed another man in the accident. Noah, with a major in hypocrisy, and not wanting to kill the golden goose, tells him to suck it up rather than confess, and soon the preacher is on his knees begging God for forgiveness.

Having struck gold herself, Terry wants more and to protect her investment, should Ted/Tad ever discover that nobody was killed in the accident, decides to marry him and rook him of all his money. That involves seducing the preacher, much to the annoyance of her lover, and getting him so drunk he can hardly stand when she hauls in a two-bit no-questions-asked celebrant to carry out the wedding.

Ted/Tad wakes up from a drunken stupor on his wedding night to find the lovers making out in the next room. After he uncovers the con, he chucks her off a bridge into the river. But she’s not dead and returning to her room and mistaking the sleeping Pete for her new husband shoots him dead. For good measure, she pumps two bullets into Ted/Tad, but in one of those tropes that seem to afflict any picture involving a preacher or religion, he is saved by his Bible. So he strangles her and buries her.

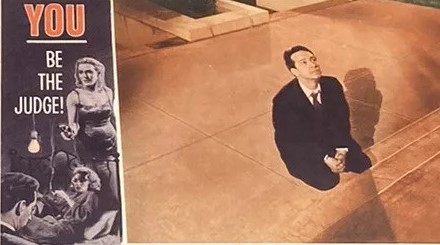

The picture ends with Ted/Tad on his knees begging forgiveness from God on the usual terms i.e. that he spends the rest of his life making sinners repent.

While spending too much time on the amnesia malarkey and the Elmer Gantry rip-off scenes, it fair picks up once Terry re-enters the scene. I said this has little style, but that’s only when you compare it to traditional film noir, which is full of contradictions and clever use of light and compositional highpoints.

But that’s not to say it doesn’t have several distinctive stylistic features, not least being light, played like a searchlight along every inch of Terry’s flesh in the opening scene. The wedding scene is a corker, Terry literally holding an unconscious Ted/Tad erect while the wedding is conducted. As greedy as he is, Pete is none too keen on his lover using sex as the lure to snap up Ted/Tad.

The murders and attempted murders are exceptionally well done, especially when the dupe doesn’t turn out to be the easy pickings Terry imagined. Under the guise of giving her a foot rub, he sits her on a bridge over a river, then yanks up the legs and sends her tumbling over.

So the last thing we expect is a bedraggled soaking wet Terry to reappear. At this point, Pete has snaffled Ted/Tad’s striped dressing gown and in, ironically, another drunken stupor, is sleeping it off, lying on his front in the bed, when the enraged Terry turns up, and kills him with his own gun.

And when Ted/Tad doesn’t drop dead after being pumped full of two bullets, Bible taking the hit instead, all we see is his hands reaching for her whiter-than-white throat.

We end with Ted/Tad on his knees.

Hollywood wasn’t in the habit of looking to B-picture directors to fill out the ranks of A-list movies, so whatever Irvin Berwick (Strange Compulsion, 1964) achieved here in his sophomore outing went unnoticed and he was as likely to pop up as dialog coach (Rough Night in Jericho, 1967), for example, as anything else.

But he does evince good performances from his cast. Lyn Stratten – in her only movie – has the easier task, she’s the standard hard-bitten blonde, but there are a couple of scenes where the vulnerable takes over from the nasty and she turns in a many-sided performance. I should point out that you’ll flinch at the brutality of the domestic abuse.

This, too, was the only leading role for Jonathan Kidd, who spent most of his career in bit parts, but he’s especially powerful when he snaps out of the drunken dream and goes hitman and invokes the God of Hypocrisy. Second and last screenplay for Jack Kevan, who co-wrote with Berwick.

As tough on faith and redemption as the more highly-praised Elmer Gantry, this seems to have slipped through the cracks.

Worth redeeming.