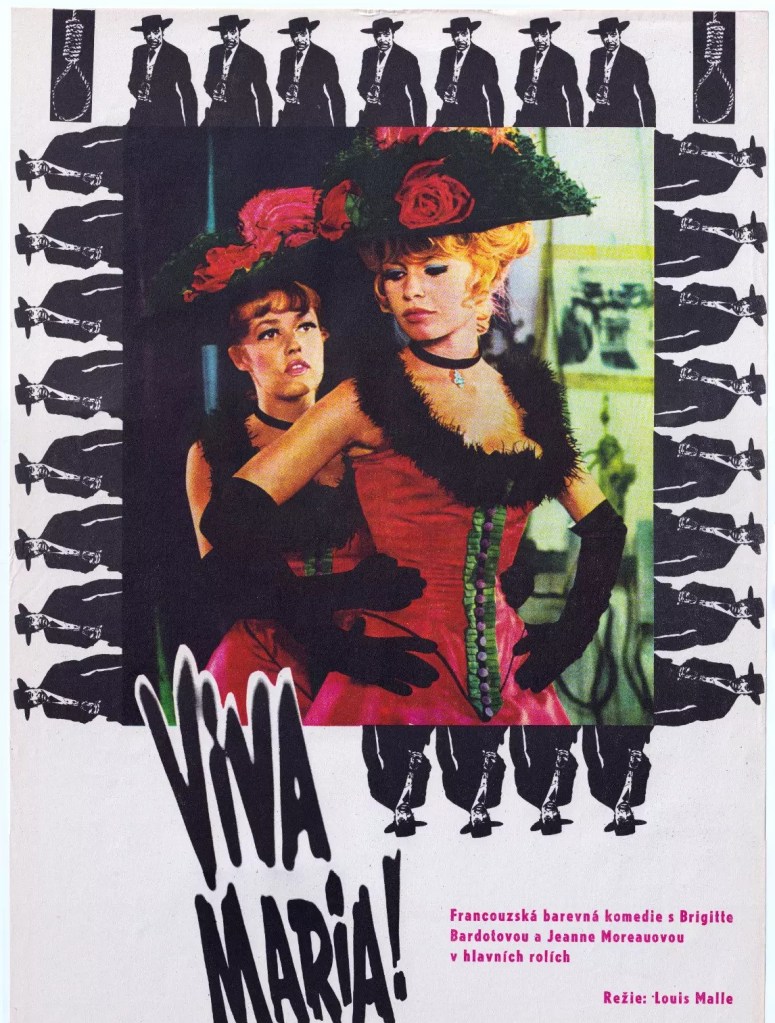

The shooting of Le Feu Follet in 1963 had proved so depressing for director Louis Malle that halfway through the filming, alone on a Sunday afternoon in his Parisian apartment, he jotted down the two pages that turned into Viva Maria! He had worked with Brigitte Bardot before on A Very Private Affair/ La Vie Privee (1962) but even with her presence it was made in virtual isolation. So he was unprepared for the brouhaha that awaited. The media had created a rivalry between the two stars – Bardot and Jeanne Moreau – which was ironic given it was a film about friendship.

Since this was Brigitte Bardot’s first movie-related trip across the Atlantic, her arrival presaged a media firestorm. Over 250 journalists, most representing international outlets, turned up for the first day of shooting. That media pressure created “an almost unbearable atmosphere.” Days were lost due to publicity commitments, as print journalists, photographers and television crews – including one from France making a 52-minute documentary – descended on the production. Such was the potential for chaos, paparazzi were banned. Bardot was more accustomed to media intrusion than her director, batting back inane questions with practised repartee. The qustion: “What was the happiest day of your life?” brought the response, “It was a night.”

This was only Malle’s sixth film. Unlike other directors who came to the fore in the French New Wave he had not first been a critic, but had attended cinematography school in Paris and his breakthrough came on the Jacques Yves-Cousteau documentary The Silent World (1956). Hired as camera operator, he was promoted to co-director. Both Elevator to the Gallows (1958) and the controversial The Lovers (1960) had starred Moreau. On the back of the critical success of Le Feu Follet/The Fire Within (1963), which won the Special Jury Prize at the Venice Film Festival, Malle struck a four-picture deal with United Artists.

He had been attracted to screenwriter Jean-Claude Carriere after becoming aware of his work on Diary of a Chambermaid for Luis Bunuel. They worked together on the script of Viva Maria! while Malle was directing the opera Rosenkavalier in Spoleto, where he had shot A Very Private Affair. Like most French filmmakers of his generation the western was “a very cherished genre.” With Viva Maria! he intended a spin on the American notion of two men, “two buddies,” in action together, along the lines of Robert Aldrich’s Vera Cruz (1954) starring Burt Lancaster and Gary Cooper.

But in movies like Vera Cruz, Fort Apache (1948) with John Wayne and Henry Fonda or John Wayne and Montgomery Clift in Red River (1948), the two stars, even if eventually settling their differences, were at odds for most of the picture.

“We thought it could be fun to put Bardot and Moreau in the same situation as Cooper and Lancaster,” said Malle. Both director and screenwriter had enjoyed a rich childhood fantasy based on the book editions of magazines like Le Monde illustre, so, in terms of locale, they provided inspiration. The movie aimed “to combine an evocation of childhood fantasies with a pastiche of traditional adventure films…it was never intended to be realistic – more projection of the imagination. Ideally, I was hoping the spectator would see it with the wonderment of the child.”

The notion of “floating between genres” didn’t sit easily with French critics and he was accused of “trying to do too many different things.” As with any big budget picture, problems multiplied, not just the difficult logistics but with the Mexican government, which, as John Sturges had found on The Magnificent Seven (1960) could take a tough line with movie makers. A previous censor Senorita Carmen Baez had stipulated that movies could not mention the 1910 Mexican Revolution, so to comply with that regulation the action was moved to an earlier date, 1904, and in an “unnamed South American country”

A combination of the number of locations – as well as Churabasco studios in Mexico City, the unit travelled to Guautla, Morelia, Tepotzlan, Cuernavaca, Vera Cruz, Puebla, Guanajuota and Hacienda Cocoyoc – and budget meant that the production could not afford to linger at any one locale, scenes had to be finished off within the planned schedule because the entire unit had to be on the move the next day.

In terms of shooting, Malle explained, “I always had to adjust and compromise…the sky was…desperately blue – the very hard light was a problem for the girls.” Ideally, Malle would have preferred shooting in the early morning or late afternoon, but time pressures and the production caravanserai meant the main scene was shot “with the sun at its zenith.”

Malle was later conscious that the film envisioned in the screenplay didn’t make it onto the screen. The irony, for example, of George Hamilton being cast as a Jesus Christ figure was lost on an audience which took him more seriously than intended. “It was comedy,” observed Malle, “but it was easy not to perceive it as comedy.” Similarly, Moreau’s “Friends, Romans, Countrymen” speech didn’t come across as humorous. “The audience either didn’t get it or took it seriously. That’s the danger of pastiche. It’s a very risky genre.”

He worried that the film’s budget – originally set at $1.6 million – and top-name stars might get in the way of the style of movie he was trying to make. At one point he suggested to UA that they cut the budget, switch to English and hire younger stars like Julie Christie and Sarah Miles, neither of whom at that point had enjoyed career breakthrough roles. The presence of the big stars “transformed the film into something else.”

The shoot was plagued by illness. Bardot and Malle were incapacitated while when Moreau slipped on a stone stairway breaking a shin bone and requiring stitches to a cut under her chin it was the third time she required time off, including suffering an affliction on her first day of shooting. An extra was killed on 24 May 1965 during the filming of the cavalry charge. Whether Malle took time off to get married to Anne Marie Deschodt on April 3 is unclear because, by then, staff were already having to work overtime to make up for lost days. The budget mushroomed to $2.2 million. Four weeks behind schedule, the movie, which had begun shooting on 25 January 1965 finally wrapped in June.

For its opening bookings in New York, at the Astor and Plaza, beginning 20 December 1965, the film was subtitled – by playwright Sandy Wilson of The Boyfriend fame no less – but thereafter was dubbed, Malle unhappy with the outcome, especially with the actress for Bardot. In the run-up to the launch, there was media overkill. Bardot was mobbed by the media on arrival at JFK airport (and also on departure) and held another press conferences in New York.

Small wonder the press were so hyped. Bardot, considered the sex symbol of the decade, was putting in her first personal appearance in the U.S. While the movie opened to “smash” business at the Astor and Plaza first run, and knocked up a decent $127,000 from 25 houses on New York wide release – not far off A Patch of Blue on $160,000 from 27 but miles behind The Chase with $292,000 from 28 – that level of box office wasn’t repeated elsewhere.

In retrospect, it was obvious Bardot lacked the marquee status the studio anticipated. The bulk of her movies had played at arthouses or seedy joints, and they had all been sold on the kind of sexuality that kept them outside the mainstream. Noted Variety, “Brigitte Bardot has not made a box office dent in more than three years but her popularity with the press doesn’t seem to have flagged.” A not unknown phenomenon, of rampant media coverage not translating into receipts. A battle with the local censor in Dallas didn’t help. So all the hoopla was to no avail – it flopped in the U.S.

Elsewhere, the publicity teams took a more upscale approach. In Paris, the Au Printemps department store, the largest in the city, devoted a series of window and internal displays to the movie promoting different fashionable aspects. It finished third for 1966 at the Parisian box office, with 602,840 admissions not that far behind Thunderball’s 806,110 admissions but had twice the audience of the nearest U.S. competitor Mary Poppins and did three times the business of Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines, the next American movie on the list.

In Britain, flamboyant hairdresser Raymond created 24 different hairstyles as a fashion tie-in while Le Rouge Baiser created a different lipstick for each of the two main characters. Overall, it proved “one of the most successful fashion tie-ups ever,” the results seen at the box office.

It opened in London’s West End at the newly-built Curzon Mayfair which specialized not so much in arthouse pictures but upmarket, classy, fare, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf (1966) followed it. It ran for eight weeks before embarking on a circuit release and returned to the West End the following year as support to another Moreau vehicle 10.30pm Summer. Bardot and Moreau were nominated for Baftas in the Best Foreign Actress section. It was ranked third out of foreign releases in Switzerland, sixth in Germany and made the top ten in Japan

Oddly enough, in socialist countries “it was very well received” and at Berlin University, according to Rainer Werner Fassbinder, “they were fascinated.” The two women represented different aspects of the struggle against repression, one promoting armed struggle, the other trying to achieve revolution without violence.

Overall it was a profitable venture. The poor $825,000 in U.S. rentals was compensated by an overseas tally of $4.1 million which meant, in the United Artist profit league for 1966, it finished seventh.

Malle only completed two pictures in his four-picture UA slate – Le Voleur / The Thief of Paris (1967) being the other. Another project set in the Amazon in 1850 came to nothing as did a separate deal to direct Choice Cuts for Twentieth Century Fox.

SOURCES: Malle on Malle, edited by Philip French (Faber and Faber, 1993) pp45, 49-54; “Bardot Due in Mexico,” Variety, December 9, 1964, p26; “Louis Malle’s Four for United Artists,” Variety, January 13, 1965, p3; “Bardot Swamped by Mex City Newsmen,” Variety, February 3, 1965, p17; “Filming Viva Maria in Mexico,” Box Office, February 15, 1965, p12; “Arnold Picker Chides Malle’s Pace,” Variety, April 7, 1965, p2; “No Newsmen at Can-Can,” Variety, April 28, 1965, p13; “Jeanne Moreau Injury,” Variety, May 19, 1965, p3; “Complete Viva Maria,” Variety, May 25, 1965, p15; “Extra Killed in Viva Maria Bit,” Variety, June 2, 1965, p5; “UA’s Viva Maria Booked for Astor, Plaza for Xmas,” Box Office, November 8, 1965, pE2; “Paris Window Display,” Box Office, November 22, 1965, pB1; “Malle Dickers UA on Three Films,” Variety, December 15, 1965, p5; “Picture Grosses,” Variety, December 22, 1965, p9; “International Sound Track,” Variety, December 22, 1965, p26; “TV Crafts Greeting to Bardot,” Variety, December 22; “Maria Viva $110,000,” Variety, December 29, 1965, p20; “Curzon Premiere for Viva Maria,” Kine Weekly, February 24, 1966, p3; “Viva Maria,” Kine Weekly, February 24, 1966, p21; “New York Showcase,” Variety, March 23, 1966, p10; “UA’s Location Plans Span Globe,” Kine Weekly, May 26, 1966, p36; “Thunderball As Topper,” Variety, June 1, 1966, p3; “1965-1966 Paris Film Season,” Variety, June 15, 1966, p25; “Story As Before,” Variety, July 13, 1966, p17; “Texas High Court Denies Viva Maria Re-Hearing,” Box Office, October 31, 1966, p7; “U.S. Majors,” Variety, January 18, 1967, p24.