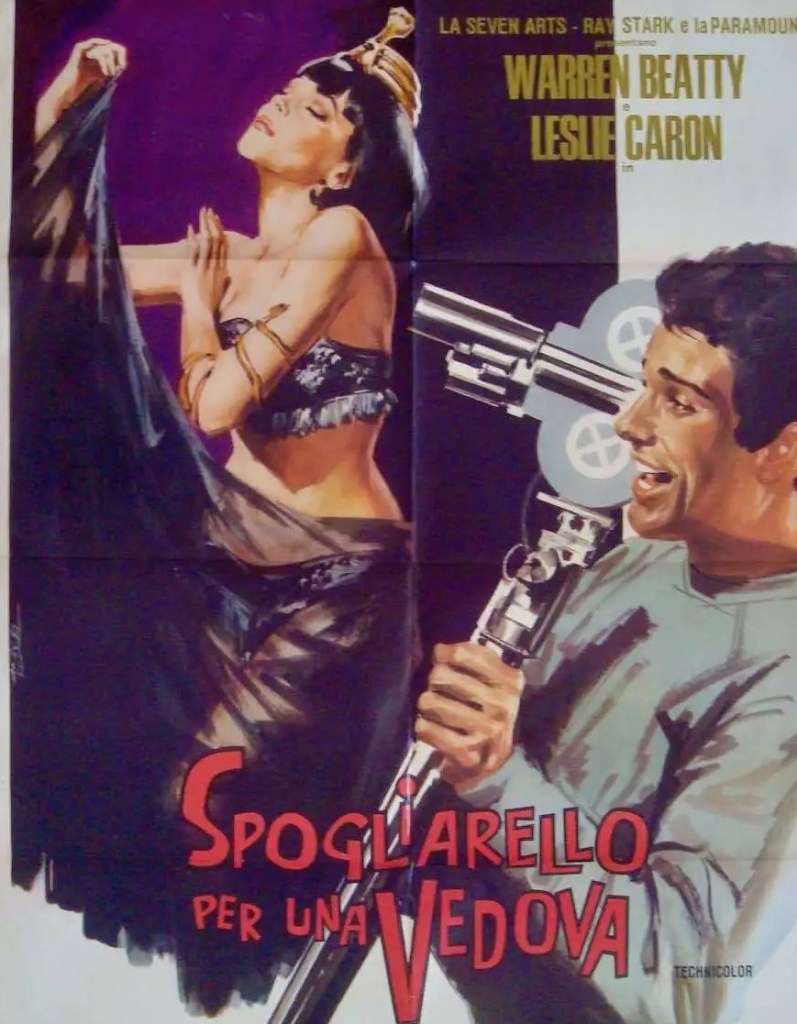

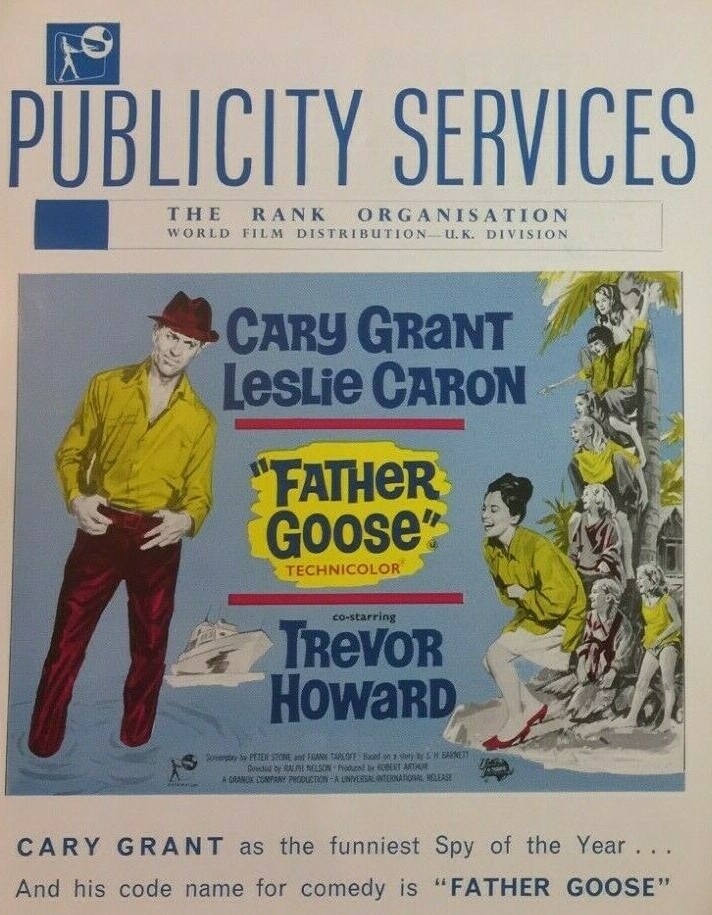

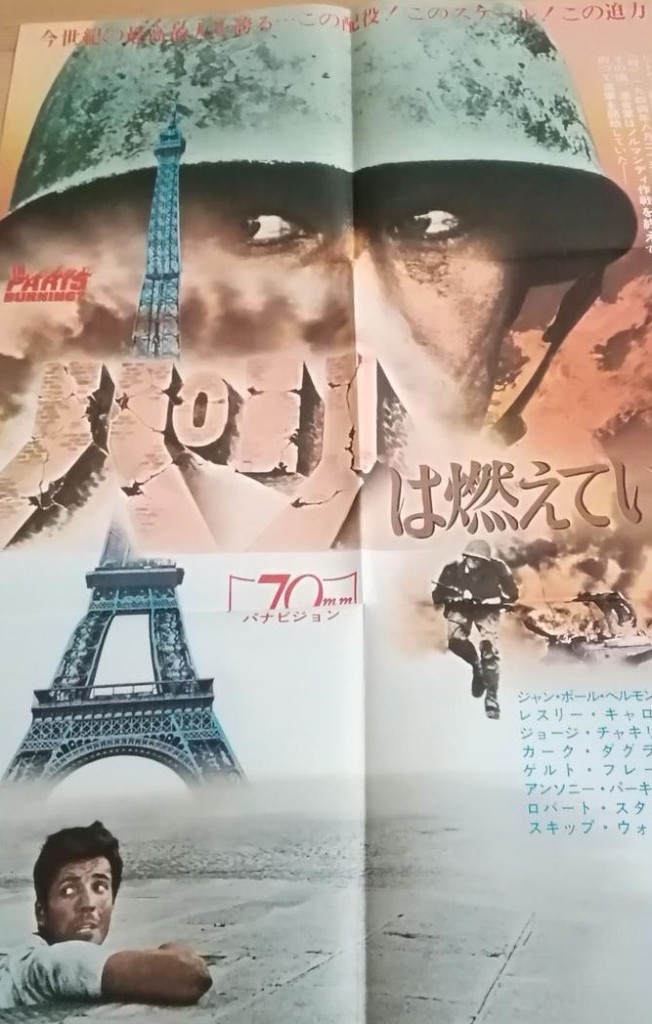

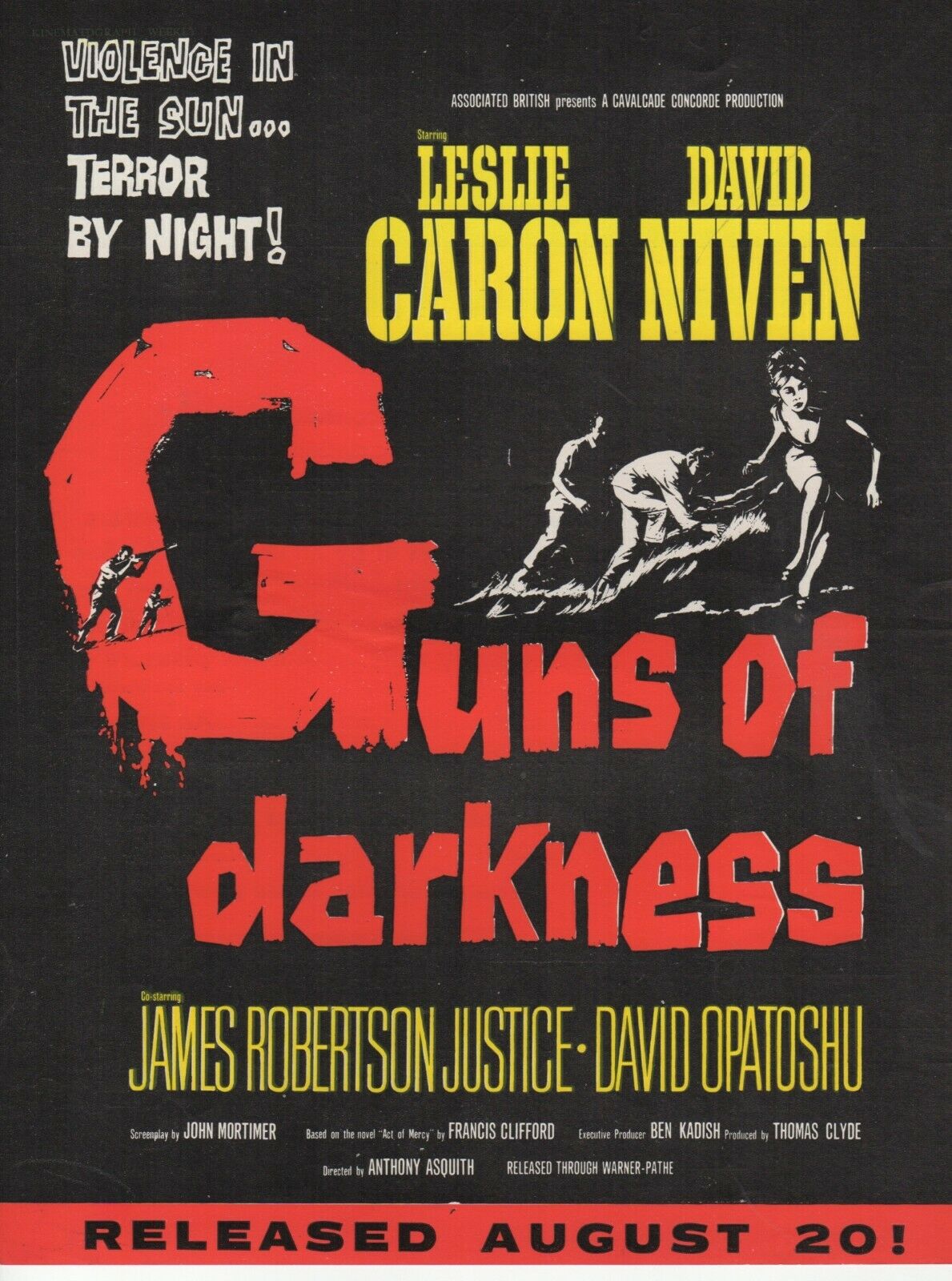

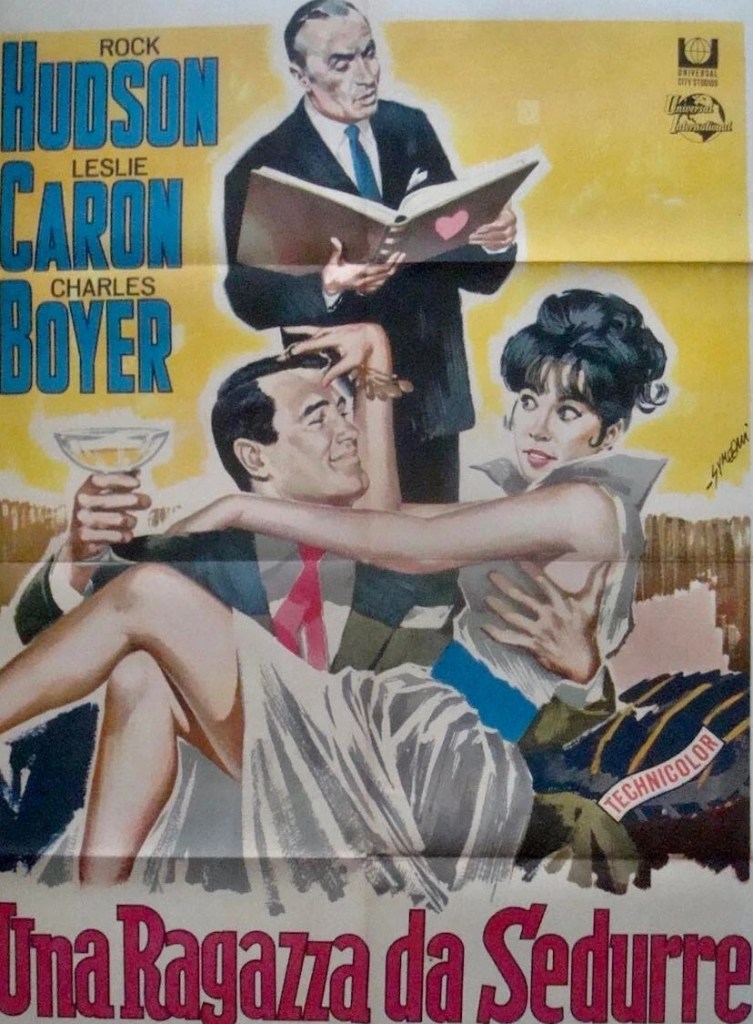

Surprisingly funny for a movie that’s long been out of favor. Starring a Rock Hudson (Seconds, 1966) who was just beginning to lose his grip on the marquee after an incredible run of box office success and Leslie Caron (Guns of Darkness, 1962) who had always seemed to just miss out on the top echelons of audience approval.

You can see why this had rapidly lost whatever appeal it originally possessed and that a contemporary crowd would turn its nose up at a man that has such success with the ladies that he has a whole stream of women carrying out his most basic chores. Except that the tale is really about him getting his come-uppance and everyone enjoys that kind of narrative.

Paul (Rock Hudson) only has to look at a woman and she melts. His job, such as it is, though he is wealthy, is to use his charm to commercial advantage. We open with him in a French court winning a case it transpires because he has seduced the female judge. The opposing lawyer Charles (Charles Boyer) encounters Paul on the way home, observing the American batting back stewardesses with ease, and the Frenchman enlists him to seduce his daughter Lauren (Leslie Caron), so much of a career woman, a high-flying psychologist, that her father fears she will turn into an old maid.

But Lauren already has a fiancé, Arnold (Dick Shawn) who, like Paul’s harem, is at her beck and call, carrying out the most basic tasks for her. Paul pretends to be a patient, his fake problem being his irresistibility which has caused a girlfriend to commit suicide. Lauren shows very little sign of falling for Paul’s charm. In order to prove that they are making progress, they go to a restaurant. To Paul’s astonishment, Lauren passes out from drinking too much champagne. He takes her back to her apartment and in the morning pretends that she has succumbed to his charms.

So now the twists come. Lauren is upset to discover that she has been seduced by a man she was determined to keep her distance. But when she finds out the truth, the tables are turned. She invents a Spanish lover which knocks Paul’s ego to hell. Plus she accuses him of impotence. Then he turns the tables again, and using one of his many fans – and a ploy that would prove somewhat ironic given Hudson was a closet gay – switchboard operator Mickey (Nita Talbot), makes Lauren so jealous that eventually he contrives to win her back and the two determined singletons, against all odds, get married.

There’s some marvellous stuff here, some slapstick at which Caron is surprisingly adept, but mostly it’s a tale of flustered feathers and vengeance for perceived humiliation, beginning with Boullard who is so annoyed that any of daughter of his is a stuck-up prude. Paul can’t believe Lauren isn’t falling at his feet and equally she is infuriated that Paul isn’t another male slave like her fiancée.

There’s a great turn from Dick Shawn as the slave and his mother (Norma Varden) who keeps on encountering Paul at his least winning. It’s a relief to see Rock Hudson not playing the stuffed shirt of previous comedies and for Leslie Caron not to be a hapless heroine. So it plays as a more effective modern comedy.

Not everyone was so keen on Caron, complaining about the lack of chemistry between the leads and that Paul would never get hooked by such a cold fish. But I disagree. Sure, it called for a lot more from the audience that the leading lady wasn’t the usual ultra-feminine model, but that made the initial romance more believable. Initially, Paul doesn’t fall for her and is seducing her as a “very special favour” to her father but once he sees the other side of her personality he changes his tune.

But I would hazard a guess that, mostly, people were annoyed with Caron because she wasn’t Doris Day and that, while this follows one formula, it steers clear of the Hudson-Day formula in making Caron a high-flying career woman. Dick Shawn (Penelope, 1966) leads an able supporting cast.

Directed by Michael Gordon (Texas Across the River, 1966) from a script by Stanley Shapiro (Bedtime Story, 1964) and Nate Monaster (That Touch of Mink, 1962).

Worth a look.